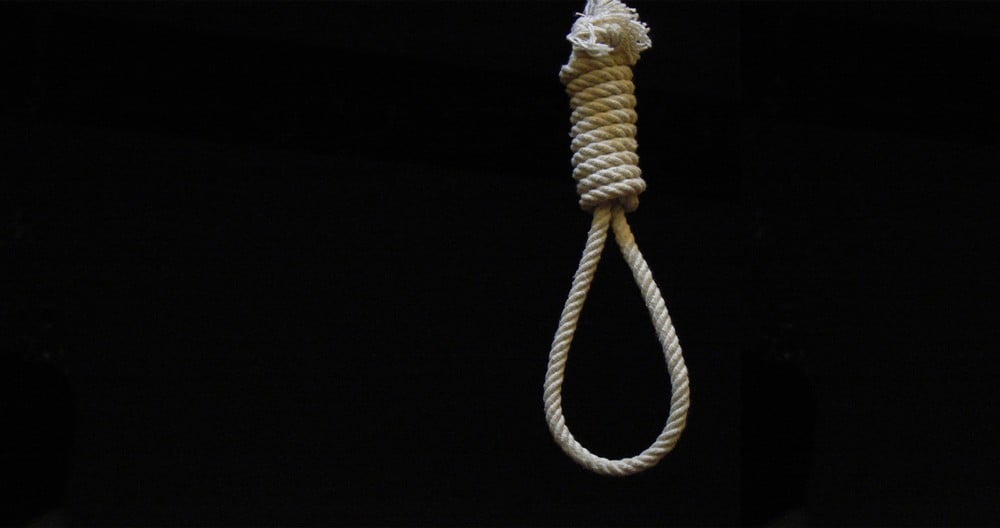

The emphasis should shift from the misplaced faith in the effectiveness of the policy to resume hangings to a sincere search for non-military options that are needed to ensure the victory of arms

The debate on death penalty has been revived at a time when the people’s emotions are running high. The Peshawar massacre has unleashed the demons of vengeance. A brutalised society has fallen for the puerile theory of answering terror with terror. Reason is at a discount. But it is precisely in such situations that reason must not be abandoned. This is necessary, among other things, to avoid the disastrous consequences of hasty, irrational steps.

Before we begin examining the pros and cons of the decision to lift the moratorium on execution of death penalty, it is necessary to make it clear that this discussion is without prejudice to the decision to go for terrorists with full force and offer them no quarter. Indeed, many among the people who stand for abolition of capital punishment demanded across-the-board military operations against terrorists and militants of various hues while their present foes were inventing ever new excuses to protect them. It is wrong to consider resumption of hanging as an essential part of the fight against terrorists. These are two different issues and must be discussed separately.

The main argument in support of capital punishment, that it deters criminals from breaking the law, has been effectively repelled many times over. Serious crime did not come down in Europe by making the theft of a horse or a loaf of bread punishable with death, it declined with an improvement in common people’s intellectual ability and their material well-being, and reform of criminal justice systems.

Saudi Arabia beheads a good number of convicts each year for a variety of crimes. Has the number of culprits fallen? In Pakistan itself, there have been more cases of disrobing of women and parading them naked after Ziaul Haq made the offence liable to death penalty than had been reported earlier. The same is the finding on the operation of the blasphemy law. We also find that the number of people awarded death penalty in this country has been falling during the moratorium period.

According to the record available with the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, the number of people awarded death sentence per year has been coming down since 2001-2003. In those three years, 1,853 persons were given death sentence, or an average of about 618 convicts per year.

The average figure for 2001-2008 fell to 459 convictions per year. During 2009-2014 (up to December 19) -- the moratorium years -- 1,645 persons have been sentenced to death, or an average of 274 convictions per year. If execution of death penalty could deter criminals the moratorium should have made them bolder. How will this argument be refuted by the defenders of hangings?

The argument that in a country like Pakistan, where the police and the prosecutors are universally acknowledged as corrupt and inefficient, and the judicial system suffers from serious deficiencies, the chances of miscarriage of justice are really great.

Over the years, many instances of innocent people having been awarded death sentence have come to light in various countries. In Pakistan, too, there have been cases in which the guilt of those condemned to death was not proved beyond any shadow of doubt.

Then, numerous flaws in Pakistan’s death penalty regime have been noted. The number of offences carrying death penalty has been increased from two at independence to 28 at present quite arbitrarily or in fits of populism, and always without exploratory studies by competent psychiatrists, sociologists, criminologists and jurists.

Laws have been made that encourage crime instead of discouraging it. For instance, the prescription of death sentence for rape and gangrape encourages culprits to murder the victims and, thus, get rid of the principal witnesses against them. The murder of little girls after abduction and rape could, in some cases at least, be due to flawed legislation.

The death penalty regime in Pakistan is also criticised for lack of uniformity and even-handedness in its application. Multiple court structures have been created for trial of identical offences and often some junior police officers decide whether a person will be tried by a normal court, where he will have the protection of due process, or whether he will stand trial in an anti-terrorism court, where respect for due process is much less.

The introduction of anti-terrorism courts has created distortions in the justice system. In a situation charged with anti-terrorism fervour, these courts can become extra keen to punish the accused rather than to do justice. At the same time, these courts lose credibility when they are seen awarding heavy punishment to trade union workers while known terrorists go scott-free because the executive is not able, or not willing, to bring up the evidence against them.

The death penalty regime in Pakistan has also become unbalanced since the enforcement of qisas and diyat law in 1990. Under this law, murder has largely been reduced to a private affair between the killer and the victim’s family. If the latter forgives the murderer, out of fear of the culprit’s capacity to cause further harm or after receiving blood money, he can regain freedom. Since he is acquitted he loses none of his rights, including the right to be elected to the parliament. Since the qisas law carries the label of a religious edict the courts have been releasing killers at any stage of trial, even before indictment, although forgiveness by victim’s heirs should be possible only after conviction.

For an example of a murderer forgiven out of fear one may recall a woman’s appearance, along with her two children, in the court of a district judge with the request that her husband’s killer should be pardoned as she did not want her kids to be killed, too.

The net result of the operation of the law of qisas is that only very poor or resourceless culprits can be punished. This has a bearing on cases in which the accused are charged with heinous crimes against the state. In these cases, courts are under palpable pressure to stay on the right side of the establishment. Indeed, the call to protect the national security state can sometimes be more irresistible than the demand for respect for religious injunctions.

These arguments make a strong case for abolition of death penalty, at least for continuing the moratorium and making it formal. The idea of hanging several hundred people within a few days must be reviewed. It is necessary to declare that the exceptions being offered with a view to making examples of the more prominent terrorists or those who have carried out more blatant attacks on Pakistan or who have planned/supervised major suicide bombings, do not alter the moratorium policy and that these exceptions constitute a temporary deviation.

It is also necessary to sift the cases of condemned prisoners to ensure that no one sentenced to death for an offence that does not fall in the category of terrorism is hanged.

There is no gainsaying that execution of convicts through a process that is not only just but also appears to be just is generally accepted by the condemned person’s family and the public at large. But execution of a person whose conviction does not appear to be just can have extremely adverse effects. This is particular true in cases involving religious extremists.

Finally, the view that the war against terrorists can be won by hanging some or many of them or by making the laws more stringent or moving towards summary trials by military courts can only be the result of lack of comprehension of the kind of war Pakistan is facing. Even the defence experts know that military operation alone will not rid the country of the scourge of terrorism. The emphasis should shift from the misplaced faith in the effectiveness of the policy to resume hangings to a sincere search for non-military options that are needed to ensure the victory of arms.

Read on next page:

Questions about miscarriage of justice have already arisen in two cases.

Shafqat Husain, who is high on the execution list, was sentenced to death for involuntary murder, based on a confession extracted from him during severe torture when he was only 14. How could he be accused of terrorism? Was the law properly read while awarding death to a person who was a minor at the time of the crime he was accused of?

Doubts about the conviction of Akhlas, who was hanged in Faisalabad last Sunday, have not been answered. His Russian passport was flashed on TV screens perhaps to fuel speculation about the role of foreign hands in terrorist attacks in Pakistan. The son of an Azad Kashmiri health specialist and his Russian wife, he came to Pakistan to see his father and protested innocence to the end. No answer has been offered to the question as to why the courts ignored the date of his arrival in Pakistan on his Russian passport, which was after the date of occurrence of the crime of which he was convicted. Moscow’s protest is not unexpected.

--I.A Rehman