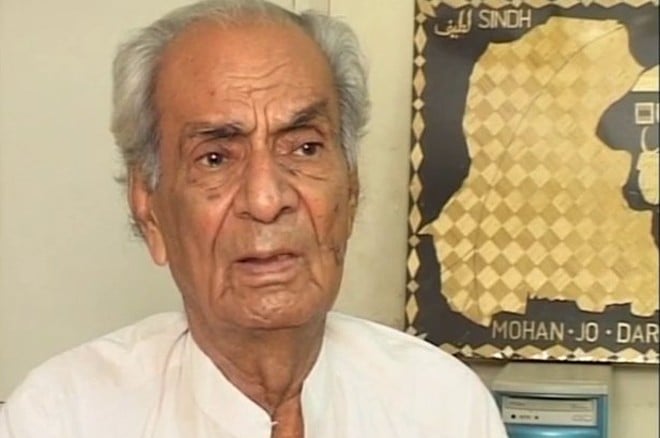

Sobho Gianchandani’s death has left Sindh’s democratic, secular and enlightened segments orphaned

The earliest one remembers of him is in the 1970s; in a two-room dilapidated dwelling in Malir, Karachi. A secret meeting is going on, there are four men gathered in one room, and in the other the entire family cuddled together. As a ten-year old child, one is curious to see what is happening but there is no way one could enter the room. Suddenly tea is requested, and mother of four children prepares tea on a kerosene-oil stove.

One gets an opportunity to enter the room as a tea bearer and has a look at the faces of some strange people with hand-written and cyclostyled pamphlets around - the child is able to read Surkh Parcham (Red Flag) on one of the pamphlets. A handsome-looking young fellow in his thirties takes the tray; the other, a darkish and sturdy man appearing to be in his forties, smiles at the child but doesn’t say anything; the third is a towering figure above all others and looks the oldest, with fair complexion and bright eyes. One later finds out that the first was Jam Saqi, the second Dr Aizaz Nazeer, and the third Sobho Gianchandani.

The three leaders of the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) from Sindh spent a major period of their lives behind bars and endured torture and trauma during dictatorships and Zulfiquar Ali Bhutto’s democracy.

Gianchandani’s death on December 8, 2014 in Karachi has left Sindh’s democratic, secular, and enlightened segments orphaned once again; the previous time it was the demise of GM Syed. Gianchandani was 94; that means he was one of the last who still remembered witnessing the promulgation of the Government of India Act, 1935; the rise of Nazism in Germany led by Hitler, the pinnacle of fascism in Italy steered by Mussolini, and the consolidation of communist power in the USSR as dictated by Stalin.

He had the honour of studying at Shantiniketan, an abode of learning in West Bengal, established by Rabindranath Tagore with the money he received when he was awarded Nobel Prize in 1913. Gianchandani commanded an exceptional memory and till his nineties narrated with cherish the stories from Shantiniketan. He often proudly reminisced, "Tagore used to call me My Man from Mohenjo-Daro."

Gianchandani was a revolutionary who drew inspiration from communist leaders such as MN Roy, Sajjad Zaheer, Jyoti Basu, SA Dange, BT Ranadive, PC Joshi, Ajoy Kumar Ghosh, Inder Kumar Gujral and Mian Iftikharuddin. He was actively involved in the Quite India Movement of the early 1940s; but when the Nazi Germany invaded the USSR the Communist Party of India (CPI) declared the fight against Germany as their primary goal more important than the fight for independence at the time. This changed the dynamics of the freedom struggle that did not go well with Gianchandani; he argued with the CPI leadership and for a while thought about joining Nitaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian Republican Army. His communist comrades prevailed upon him and he remained within the CPI fold.

That was the time when Hindu fundamentalist organisations such as the RSS were trying to get hold in Sindh and many of his Hindu friends and even relatives had a soft corner for RSS to fight against the Muslim demand for Pakistan. He was one of those Hindu activists who could stand against the RSS infiltration in Sindh.

When the CPI started supporting the Pakistan Movement as if it was a ‘national movement for self-determination’ (a common term that was bandied about in the communist parlance of that period), Gianchandani again felt uncomfortable but followed the dominant CPI policy.

After the creation of Pakistan, he remained an active member of the CPP till it was banned in 1954 under the Governor Generalship of Ghulam Mohammad. Then, with the state persecution on the rise against the communists in Pakistan, they found alternative outlets within the mainstream political parties of East and West Pakistan led by leaders such as Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Maulana Abdul Hameed Bhashani, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, GM Syed and others.

With the military takeover of the country in October 1958, most of the politicians were put behind bars or barred from politics at all; Gianchandani was under house arrest in Larkana from 1959 to 1964. That was the time when he was able to experiment with new varieties of rice and wheat on his land. "I increased the agriculture produce from my father’s land five times", he often boasted. In all, he spent around ten years in jail, another ten years under house arrest and another decade or so underground, trying to escape from arrest and torture. He was a true son of the soil, refusing to migrate to India even when GM Syed advised him to move after the imposition of Martial Law in 1958. He preferred to stay back and do something for his people here, rather than being a Sindhi alien in India.

In the late 1980s, when the communist dream came to an abrupt end, most of the former communists either joined NGOs, turned religious, or spent time regretting they were ever communists; but Gianchandani never regretted. He thought his life was well-spent and was proud of his contribution to Sindh in particular and to Pakistan in general.

He even tried his hand at parliamentary politics by contesting for a National Assembly minority seat in 1990; he had won the election against Bhagwan Das Chawla, but the invisible hand of the establishment maneuvered to deprive him of his last chance to become a member of parliament. Even after the announcement on PTV of his victory, a recounting of vote was initiated at the behest of Chawla, a Hindu millionaire who claimed to have spent over seven million on his campaign, and ultimately Chawla was declared a winner.

Gianchandani wrote short stories, essays, poems, research papers, personality sketches, editorials, newspaper columns and articles, book introductions and prefaces; all are scattered and need compilation and translation -- even his autobiography that was serialized by a Sindhi literary journal in Karachi deserves translations in other languages.

One of the happiest moment of his life was when he won an award of excellence from the Academy of Letters. He was the first Hindu and probably the first Sindhi writer to get this award in Pakistan. When asked, why he accepted that award during the tenure of General Musharraf, he coyly said, ‘I did not get it from him, it was a committee of learned people who awarded me, and I pretended to be ill and sent my daughter and son-in-law to receive this award from Sindh Governor Ishrat-ul-Ibad.’

It was probably his right to be happy in the last years of his life; rest in peace Comrade Gianchandani, the child who brought you tea in that room, fondly remembers you; and so do millions of secular dreamers of the sub-continent.