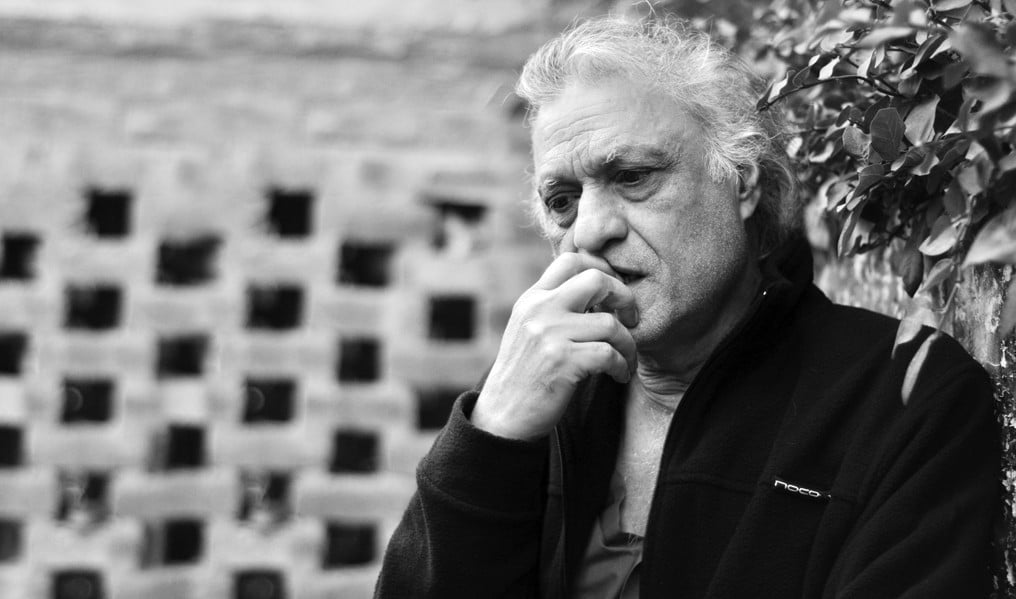

Sarmad Sehbai talks about poetry, drama and the influences that shaped his creative path

In this age when scholars and readers are eager to think across the disciplines, to discern the underlying matrix of an artistic moment beyond fixed notions of identity or traditional expectations, Sarmad Sehbai comes across as a man from the border. His restless curiosity has kept him always on the move, going where it pleased him, carrying no baggage; such perhaps is the ideal, yet also, in large measure, his inescapable reality.

Poet, dramatist and a nomad at heart, he keeps returning -- physically or imaginatively -- to the various locales that have formed him.

As a singular figure as any, he never devoted the bulk of his efforts to a chosen genre. Rather, he came and went, alert to creative openings, following his ideas in and beyond such practices simultaneously, alternately, sequentially. If some consider him essentially a playwright (Aik Moazzaz Shehri Ka Rasm-e-Janaza, Phandey, Ashraf-ul-Makhluqat, Tu Kaun?, Bachon ka Park), his fascination with writing poetry and the mysteries of language remains nonetheless central to all his output. As a poet (Unkahi Baaton ki Thakan, Neeli ke Sau Rang, Pal Bhar Ka Bahesht, Mah-e-Uriyan), his understanding of history combined with the expansive flair of a born raconteur to set his imagination in motion, is remarkable.

Taken as a whole, his great versatility should be regarded as an ongoing method in his art of the opening, of uncovering paths.

Below are excerpts of his interview conducted over several sessions in Islamabad and Lahore:

The News on Sunday: Your father, Asar Sehbai, was a scholar and poet of Persian and Arabic. Was he any influence on your early training?

Sarmad Sehbai: My ancestors were Hindu, and both my parents were Kashmiri. My maternal grandfather who used to practise law belonged to Daska. My father had degrees in Philosophy and Law, and used to practise in Srinagar. From young age, I was exposed to the tradition of learning from classics. My mother was a great storyteller who would tell me stories about Kashmir. I was born in Sialkot, and lived most of my early life there. In 1951, we shifted to Lahore, and I started going to Junior Model School in Samanabad. My father had tremendous influence on me during my formative years but soon enough I dissociated myself from him. My friends would taunt me on having a proverbial Freudian relationship with him upon turning a rebel. I was totally against ‘tradition’ and wished to become part of the ‘modern’ idiom.

I knew all about the structure of a ghazal (there was to know) by the time I matriculated. I became much familiar with the entire tradition of linguistics through magazines and literary journals we used to subscribe to, such as Alhamra, Humayun, Qandeel, Naqoosh and Mah-e-Nau. When Pakistan was born, articles on how to improve Urdu pronunciation would appear in magazines aimed towards promoting the language.

My interest in theatrical arts, however, came from my mother who would narrate stories in Punjabi, weaving scenes into her oration. The entire family would gather around her. These were my first lessons in characterisation and dialogue.

TNS: Can you recall the years of your early development as a poet?

SS: I began by writing poems for children when I was still in school. When I joined Government College in Lahore years later, it turned out to be a different world altogether. There was no culture of communicating in English in the background I had come from, and here it was a ‘colonial’ culture. I could see a change take place in me, and I began to gain fresh insights in classics. I could barely speak English yet I could write in English. We had a professor who was impressed by my article, who invited me home, and encouraged me to speak the language. He asked me questions I couldn’t answer. From the next day onwards, he decided to conduct the class in open air where he would sit next to me and start off in English.

When I hit the graduate programme, I was confident enough to break the colonial construct with such strong ideologies as Marxism, Existentialism and the Third World Politics. Afro-Asian politics awakened in me a new vision that took me into another direction.

TNS: Tell us about your foray into theatre as a playfield of radical or avant-garde ideas?

SS: During my Masters programme in English Literature, I had read primarily Shakespeare and poetry. I used to think that drama was either a sub-genre or a secondary literary form, and that poetry was the real thing. Soon after Masters, I landed the job of commissioning writers to write dramas for PTV. (Plays used to be telecast live in those days, and my job was to coax two plays each week, and pass them on to the producer). One day, the playwright backed out, and the producer, Yawar Hayat, convinced me to write the play in his place to fill the slot. So, my first play that I wrote in two days was called, ‘Lamppost’, written in 1968, acted out by Mohammad Qavi, Enver Sajjad, Farooq Zameer and Salim Nasir. The play met extreme reactions: while the Bengalis living in East Pakistan flooded us with telegrammes of appreciation, the PTV establishment abhorred the play and charge-sheeted us.

It was an impressionistic play, without a plot or a storyline per se. There’s a tramp who goes to the slums to witness life there: a wife who throws her husband out in the cold, a prostitute, a beggar, and so forth. But we don’t know the true identity of this ‘tramp’ who ends up developing a relationship with these characters in a very subtle way. The play implies that he’s some sort of a divine being. He is mysteriously charming. Then enters a professor followed by a ‘majzoob’ who defies divinity and quotes Bulleh Shah. The ‘tramp’ pulls an apple out of his pocket, juggles it around, and finally throws it at the majzoob who eats it up and subdues. It was a radical play for those who’d been fed on drawing room comedies. The reaction to the play made me indignant and I decided to quit PTV. That was a turning point in my career when I moved towards theatre.

TNS: How would you respond to Hash as an advocate of catharsis theory?

SS: Looking back in retrospect, one can see strains of a very strong leftist sentiment, of revolution, class struggle and class hatred in the air, in those days. On the one hand, there was an orthodox brand of Leftists, like Sibte Hassan, Safdar Mir and Faiz Ahmed Faiz while, on the other, there were the so-called Existential Leftists -- not, however, by their own admission. I am an Absurdist Anarchist.

The existentialist wants to know why he’s making a choice. For instance, if I am a militiaman, is it my personal choice to kill another man? Same is the case with the Marxists: Was it a personal choice coming out of an experience or was it simply joining the herd? For an orthodox Marxist, the existentialist is obviously a threat. In Sartre’s play, Dirty Hands, a middle-class man is employed to kill his boss, but he can’t because he fails to find a plausible reason to kill. But when he catches his wife with his boss, he takes the gun in hand and commits the crime of passion. The communists find him ‘unreliable’ because he’s unsure, cannot follow the party discipline, and has no right to live.

Like in Catholic faith, you have a confessional where you perform dutifully and mechanically, like liturgy. That’s the important element you get to see in those plays. In Hash, those who smoke ‘joints’ (the Marxists) make a bourgeois, retrogressive and debauch statement. I tried to show why the younger generation is hooked on dope. There’s a character of a revolutionary who has renounced his culture because he’s disappointed. He’s caught and has to go through a trial before persecution. When he’s being interrogated, he answers: I want to bring about revolution but I am not an ‘employee’ of revolution. It was about a middle-class radical who wishes to bring about change but is constantly hounded by the authorities -- the right wing.

I used to say: Piano is not a bad thing in itself; we just need to liberate it from the clutches of a particular class and release it to the other. For the conventional Marxist, everything or anything that was aesthetic or pleasure yielding was an anathema because of his orthodox views.

TNS: How does dance as an indigenous form of liberation work as a metaphor in your Punjabi play, Panjwan Charagh?

SS: Panjwan Charagh was staged in 1983. I was in Islamabad during Zia-ul-Haq’s time, thinking of doing ‘house theatre’. I read out the play in Punjabi to Madiha Gauhar, Imran Aslam, Sarwat Ali and Salman Shahid. I proposed to get all the theatrical groups at the college level together and stage a collective play. On our own, we could not survive beyond 2-3 plays that we staged under the Ajoka banner. Finally, Salman Shahid directed the play and Rashid Rahman pooled in money to get the production going.

When the general came into power, MRD launched a movement in Sindh. The play was about Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, not in an intentional way but in an oblique sense, shown as a paralysed man on a wheelchair. We discover that he is incapable of dancing, and that his ‘mujawwars’ are also truncated. Referring to Qalandar’s life story who was captured and chained but who struggled to dance while the chains melted and the prison walls collapsed, we have forgotten to dance, to rebel and to liberate ourselves. The protagonist says: "Sadey wich koi nahin jaira apni pairi raheen nach sakey. Aithan sarkaran noon tey putli da nach pasainda ae".

The development pertaining to the vernacular in Punjabi is a product of Najm Hosain Syed school of thought. Let me quote an incident: We were sitting in Syed’s house where Shah Husain’s kafi was being recited in heavy-set literary Punjabi. When we stepped out, we started to speak in Punjabi colloquial. We asked Najm Syed how he responds to the alchemy that languages exude according to the demand of the time. He would say, you have to de-class yourself and the language. The argument is that the poetic process defies that. It does not select its diction according to its audience because that comes as a spontaneous outburst. Your passion selects the words almost unconsciously because the poetic process is unpredictable. That is a conscious restraint on your poetic impulse.

TNS: Why is Manto extraordinary, in your opinion, among all post-partition writers of our times?

SS: If you look back at times when Manto was alive, you may wish to draw a parallel with Ghalib’s times, as a point of reference. Ghalib’s letters in prose are free from the trappings of verbosity and grandeur. ‘Qadir-ul-Kalaam’ is a poet who possesses words like they were odalisques in attendance at his court. Ghalib’s relationship with his art was not one of possession but of ‘ishq’, yet he was ‘Qadir-ul-Kalaam’. In his letters, Ghalib employs a humane, innovative, and interesting prose.

Manto, almost always, begins his books with a couplet from Ghalib. They both celebrated poverty -- Rang layegi hamari faaqa masti -- while the Progressives marched towards romanticism. Bombay Talkies of the time had the same mood as that of the Progressives. If you look closely, Sahir Ludhianvi rose to prominence through the film songs that he wrote. Their poetry was a synthesis of the two early movements in art, naturalism and romanticism, mixed with Marxism.

Akhtar Shirani is another important exponent in this scenario with whom came sensuousness in poetry. Prior to him, poetry was fairly cerebral. Take Iqbal, for instance, where everything is based upon sound and theory, where structures turn Baroque bereft of warmth. Ghalib, on the contrary, lyricises and eroticises with the help of metaphor.

Manto’s prose carries French and Russian influences. You find Chekhov, Maupassant, Gorky, and even Ghalib’s prose and verse rolled into a smorgasbord. You find in him Ghalib’s heroism and suffering, and what you don’t is the complexity of Ghalib’s imagination, of making the impossible possible, of bringing ‘sukhan-e-muhaal’ or the metaphysical conceits into the realm of the explicable.

In my article, ‘The Politics of Exclusion’, I wrote why the Progressives eventually turned against Manto. The background is that Sajjad Zaheer wrote a novel called, London Ki Ek Raat. The hero, Hiren Pal, is in love with Sheila but he leaves Sheila in the lurch when he decides to join the fight for freedom. This became the template for the Progressives, hence ‘Mujh se pehli si mohabbat meray mehboob na maang’. Here, the first principle of femalehood is reversed in favour of patriarchy. In Progressive writings, the beloveds neither speak nor protest; they only dog trail like romantic ideals, as in Sheila’s case. What Manto did was he met Sheila, and handed her over to Saugandhi who brought her on the road. The poet says: ‘Laut jaati hai udhar ko bhi nazar kya keeje’. Until now, we had been looking at these sex workers merely as victims of sexual oppression but now we have Sheila among them.

Faiz never goes there; he only commands action. And when he walks, he falls: ‘Jo chaley to jan se guzar gaye’. When he talks about revolution, he brings in theology: ‘Hum daikhen ge’. Men don’t bring about revolution, only divine intervention does. Even there, men don’t move themselves; they will ‘be seated’ on the throne of power, the ‘masnad’. There is a sense of cerebral suffering among the Progressives.

Manto was feeling poverty and oppression on a physical level. He was living it. His suffering was a lived experience with a sickening pathos to it. To him revolution did not mean sickle and spade or labour and farmer; revolution also exists in revolutionising language, form, and ideas. Manto is the quintessential post-partition author. My thesis is that Manto also inspires modern poetry of the 1960s. Poetry of the ’60s had a different approach, excluding N. M. Rashid and Meeraji, before Manto -- the tendency to look at objects and turn them into images. When Manto wrote ‘Phundaney’ and ‘Sahab-e-Karamat’, critics like Iftikhar Jalib ended up devoting fifty pages to them because Manto gave a cue not only to the poetic idiom but also to modernism itself.

TNS: What kind of a philosophy is embedded in word?

SS: When you impose form over matter, you fail. The chemistry between form and passion is such that it should not show. You said a word and the word dissolved into a state, a feeling. If it stood between us, there is a problem because you would be impressed by the word. The word should vanish, should melt into a feeling. Narration is a craft that helps a feeling to emanate. But narration differs from the experience. An experience is fragmentary and chaotic; narration and language are a sensible, intelligible craft that one understands and translates feelings into.

Like Taufiq Rafat says: "Words have a posthumous tone". As soon as you utter a word, it becomes a thing of the past. The writer tries to bring the experience into the present by making it go through the differing process of narration. This is what you call ‘art’. "Zikr us parivash ka, phir bayan apna / Ban gaya raquib akhir jo tha razdaan apna". Narration makes the reader the writer’s confidant. ‘Zikr’ is experience; narration ends where it is brought into the present. That is when the confidant turns into a rival.