In her work displayed at the Khaas Gallery in Islamabad, Sobia Ahmed not only references history but also painting

Sobia Ahmed’s miniatures, on show at Khaas Gallery in Islamabad entitled, Who Is Afraid of Green? are characterised by a subtle gesture that makes tragic events incomprehensibly poetic. She expresses her personal reaction to this tragedy interwoven in distinct aesthetic elements, creating a poetic scenario that reinforces the nature of the atrocity -- it leaves it in the hands of the viewer as an open field from which it is impossible to withdraw one’s gaze.

The premise of referencing history, such as in the work, Once Upon A Time in 1947, is never intended to be concerned expressly with the politics of violence, nor is it meant to be prescriptive. Sobia Ahmed shares an active interest in history; be it a collective or a personal one. Her desire to question notions of political, social and religious conformity and how various systems of control and order originate, reinforcing the philosopher and cultural critic, Slavoj Zizek’s claim that: More than ever, the battle to be won is ideological.

As important as understanding ideology, is understanding the role of history in its formation. Questions are often asked by socially and politically motivated artists and accompanied by a desire to make art that becomes a means of protest in itself. Work that challenges long-held belief systems, political structures or even seemingly innocent nostalgia for the long-dead past, prompts the viewer to rethink the status quo and reconsider how one act gives way to another.

Even something originally designed for good might inadvertently get translated into something malign. Sobia addresses the terrible irony of this in her show in her own distinct way. Perhaps, we are in danger of being too didactic in our interpretation of past and present events, perhaps thinking or mindsets can prevail even after regimes have fallen.

The Hungarian theorist Ferenc Miszlevitz argued that: ‘Be careful when you suggest that something is over; it is over and it is not.’ As Sobia Ahmed’s work shows, the cycle has perpetuated, her subjects often seeming detached from their surroundings; going through the motions of life but yearning for nature and the rhythm of a long past era. Looking at Ahmed’s work, we are positioned at the crux of a dichotomy between criticism and celebration. ‘Reading’ these miniatures is not clear-cut, as there is beauty here, even in the midst of physical manifestations of totalitarian power.

While referencing history, she draws from events, imagery or the by-products of ideologies in their practice, but making work in the context of a historically important and dramatic period of time is not easy, especially when trying to locate the self in a country that is changing rapidly. Ahmed blends the techniques associated with old master painters with the thousand-year history of Persian miniature tradition to create apocalyptic imagery. Given the media’s constant rumblings of war and revolution, Ahmed’s paintings provide a biting commentary on the troubled dark side of the human condition in the 21st century.

Sobia Ahmed uses observation to counter a fascination with what she calls ‘the absurd actions of man’. She watches people intently, observing the common man caught in his given ‘role’: helpless, despairing, hedonistic or willfully ignorant. However, she chooses to address this existential anxiety by investigating man’s foibles with an uncovering of his exploitation and torture.

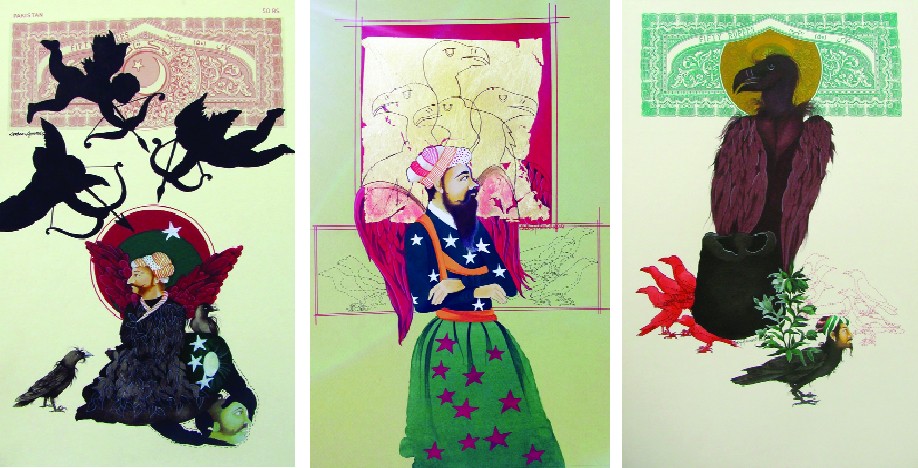

State and religious figures of authority, such as parodies of the Mughal emperors striking similarly stilted poses as in royal manuscripts and folios, often find themselves protagonists of her masterful drawings. Sometimes depicted as the corrupt and abusers, often times derided as figures of fun, and at other times revealed as terrifying personifications of punishment, Ahmed reveals the perils of investing faith in humans and systems that might be exemplary but are ultimately fallible.

She is particularly adept at using her meticulous drawings and painting skills to seduce us into looking in wonder at what often unfolds into disturbing scenes. Using humour and satire as a device to upturn received notions of ‘normal’ social behavior, long held religious rituals or collective group activities, she provokes us to question the ease with which we accept even shocking occurrences and behavior as simply part of everyday life.

The protagonist of the works is often subject to Sobia Ahmed’s own interpretation of events; restaged and altered by the addition of stars and stripes of the American flag, patterns on certain parts of the body, or vultures and rows morphing between human, plant and strange, god-like ancient idols.

To say that the works of Sobia Ahmed build in their aesthetic arrangement, their serial accumulation, an analysis of the question of representation does not in any case get in the way of their dialogical nature. For that matter, herein lies the potency of these works, in building an analysis while avoiding at the same time any conclusive simplism. They owe their potency to their great aesthetic quality among other things. Ahmed works in the detail and sensitivity, and it is for this matter that she does not contend herself to referencing history alone; she also references painting.