Like conjoined but estranged twins, Pakistan and India have also been tied together by an eternal comparison between Muslims and Hindus

A few months ago, I was invited to a conference in India on how India was perceived by its South Asian neighbours. While contemplating the subject, I began to think how India’s perception in Pakistan was in fact created. Interestingly, this investigation led me to the Pakistan Movement and to the creation of Pakistan.

Like conjoined yet estranged twins, Pakistan and India perceive each other as the ‘other,’ and the ‘other’ as a self reflection. However, while one part of India’s identity had to take into account Pakistan’s creation [or secession], for Pakistan, I argue, India was a much more important component of its identity. Pakistan’s identity as ‘Not India’ therefore became a defining feature of its identity, I maintain, and still shapes its outlook.

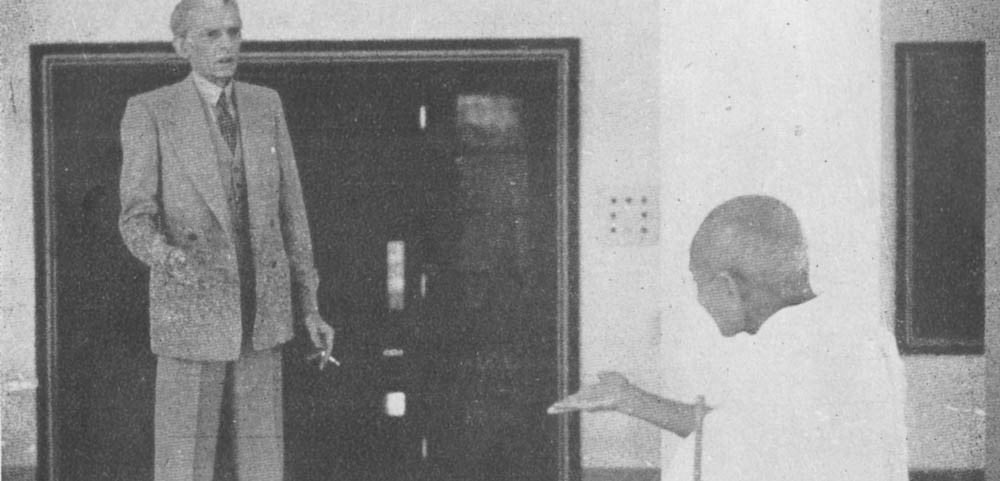

Pakistan was created on the basis of the Two Nation theory which argued that Hindus and Muslims were separate nations which could not live together. Hence, both required a separate ‘homeland.’ Jinnah articulated this argument many times, and in his presidential address to the All India Muslim League in March 1940 in Lahore [where the Pakistan Resolution was also passed] said:

"The Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs, and literature[s]. They neither intermarry nor interdine together, and indeed they belong to two different civilisations which are based mainly on conflicting ideas and conceptions. Their aspects [perspectives?] on life, and of life, are different. It is quite clear that Hindus and Mussalmans derive their inspiration from different sources of history. They have different epics, their heroes are different, and different episode[s]. Very often the hero of one is a foe of the other, and likewise their victories and defeats overlap."

Therefore both communities required a separate country--Pakistan for Muslims and Hindustan for Hindus [in fact for a long time after independence, Pakistan kept referring to India as Bharat, in order to further underscore its ‘Hindu’ character]. The creation of Pakistan, hence, was necessitated by a Hindu India--Pakistan was the Muslim mirror image of a Hindu India.

This notion of Pakistan being purely Muslim was apparent very early in its history. A Hindu member of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan faced questions when he argued that he was a Hindu but also a Pakistani. Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya, highlighted the convoluted nature of Pakistan’s identity in a speech during the debate on the infamous Objectives Resolution in March 1947. He noted:

"Will they both call themselves Pakistanis? Then how will the people know who is Muslim and who is non-Muslim? I say, give up this division of the people into Muslims and non-Muslims and let us call ourselves one nation. Let us call ourselves one people of Pakistan. Otherwise, if you call me non-Muslim and call yourselves Muslim the difficulty will be if I call myself Pakistani they will say you are a Muslim. That happened when I had been to Europe. I went there as a delegate of Pakistan. When I said "I am a delegate of Pakistan" they thought I was a Muslim. They said "But you are a Muslim". I said, "No, I am a Hindu". A Hindu cannot remain in Pakistan, that was their attitude. They said: "You cannot call yourself a Pakistani". Then I explained everything and told them that there are Hindus and as well as Muslims and that we are all Pakistanis. That is the position. Therefore, what am I to call myself?"

This dilemma still remains for most non-Muslim Pakistanis.

Pakistan’s definition of itself as the ‘Muslim’ country, and India as the ‘Hindu’ country, meant that Pakistani textbooks--throughout its history--have treated Indians and Hindus as synonyms. These books have also emphasised the perpetual enmity between Hindus and Muslims, to illustrate the historic need for Pakistan. This focus was not a product of the Islamisation process under General Zia-ul-Haq as most commentators maintain, nor does it even find its birth in the radical policies of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. In fact, this process began as soon as Pakistan was itself created--thereby highlighting its critical role in the creation of Pakistan’s identity.

Very soon after its inception, the Government of Pakistan was of the opinion that all curricula should be infused with ‘Islamic ideology’. The first minister for education, Fazlur Rahman, noted at the first All-Pakistan Education Conference in November 1947s, that: "It is, therefore, a matter of profound satisfaction to me, as it must be to you, that we have now before us the opportunity of reorienting our entire educational policy to correspond closely with the needs of the times and to reflect the ideas for which Pakistan as an Islamic state stands." He again emphasised in February 1949: "But mere lip-service to Islamic ideology will be as foolish a gesture as Canute’s order to the waves of the sea. We must see to it that every aspect of our national activity is animated by this ideology, and since education is the basic activity of the State I realized that a start had to be made there."

This ‘Islamic ideology’ was rooted in the Two Nation theory, and necessitated that the government undertake the project of textbook writing--too dangerous to leave to private enterprise--and therefore a certain view of ‘India’ and ‘Hindus’ was perpetuated.

From the beginning, but especially beginning with the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970’s a negative view of Hindus was reinforced. For example, as early as grade four and grade five students were taught that ‘the religion of the Hindus did not teach them good things,’ and that the ‘Hindu has always been an enemy of Islam.’

At the higher levels, this indoctrination is even more present, and even blatant lies are written. For example the social studies book for class eight notes, "In December 1885, an Englishman… formed a political party named Indian National Congress, the purpose of which was to politically organize Hindus." The same textbook then goes on to simply fabricate facts and notes: "Therefore in order to appease the Hindus and the Congress, the British announced political reforms. Muslims were not eligible to vote. Hindu voters never voted for a Muslim…"

Even the Musharraf and post-Musharraf era textbooks which were supposed to be ‘enlightened’ exhibit the same antagonism towards Hindus. The 2014-15 social studies textbook for grade eight notes that both the British and the Hindus "conspired against the Muslims to turn them into a poor, helpless and ineffective minority." In the same chapter on the Pakistan Movement the textbook establishes that: "The introduction of Minto-Morley Reforms was another painful factor for the Hindus. They were not prepared to tolerate any such step which benefitted the Muslims. So they became violent, and freely damaged government and public property."

With ‘Hindus’ being denounced in such clear terms, no wonder there is a very negative perception of the Indian National Congress [perceived to be completely Hindu] and India in the minds of Pakistanis.

Social scientist Rubina Saigol has aptly described the main aim of these textbooks in that: "It appears that Pakistani public school textbooks were not written to serve the pedagogical imperatives of intellectual development and the inculcation of critical thinking. Rather, they were written to perpetually justify a divisive ideology of rupture which had to be continually reiterated in the construction of national memory."

This hatred towards Hindus was not just confined to the pre-1947 period in Pakistani textbooks and extended to the post-independence period where Pakistani Hindus [especially after the secession of Bangladesh] were dubbed as agents of ‘Hindu’ India. The social studies textbook for grade five succinctly noted the ‘real’ reason for the breakup of Pakistan. It stated: "After the 1965 war India conspired with the Hindus of Bengal and succeeded in spreading hate among the Bengalis about West Pakistan and finally attacked on East Pakistan in December 71, thus causing the breakup of East and West Pakistan."

Thus a liner correlation between Hindus and India has cemented anti-India perception in Pakistan for decades.

In all these textbooks, it is never mentioned that presently India has almost the same number, if not more, of Muslims as compared to Pakistan. Obviously this information would complicate the clear distinction between ‘Hindu India’ and ‘Muslim Pakistan.’When Indian Muslims are mentioned elsewhere in the media, it is often only to highlight their plight, and hence reinforce the Two Nation theory. Even when there are prominent Indian Muslims, they are dubbed as not ‘Muslim enough’ by Pakistanis.

Another factor which fuelled anti-India sentiment was and is the fact that except for Jinnah, Liaquat and a few other stalwarts and Islamic leaders, all ‘heroes’ mentioned in textbooks are soldiers who died in wars with India. For example, in the Punjab Urdu textbooks from the primary school level upwards contain chapters on military personnel who won Pakistan’s highest gallantry award, the Nishan-e-Haider, in battles against India. Hence the Urdu textbook of the Punjab Textbook Board for the year 2014-15 for class four has a chapter on Major Aziz Bhatti [chapter 12], the textbook for class five has a chapter on Hawaldar Lalik Jan [chapter 17], Sarwar Mohammad Hussain Shaheed is the subject of chapter 24 for the textbook for class seven, and the text for class eight at chapter nine details the martyrdom of Naik Lal Hussain Shaheed.

The promotion of war heroes as general heroes for everyone to emulate has not only limited the number of career paths youth [and parents] consider in Pakistan--the military is always one of the top career paths--it also solidifies their attitude against the ‘enemy’ which almost always means India. In fact, a number of times textbooks only clarify later in the chapter that the ‘enemy’ is India since from the beginning it is taken for granted that students will automatically assume that it is India.

In addition to the promotion of war heroes, in the past few decades there has been a conscious glorification of war, especially in terms of Jihad. For example, in the curriculum document for primary schools in 1995, it was stated that the teachers should strive to create a feeling, ‘…among students they are the members of a Muslim nation. Therefore, in accordance with the Islamic tradition, they have to be truthful, honest, patriotic and life-sacrificing mujahids.’

Even in the so-called ‘enlightened’ period of the rule of General Musharraf, the theme of inculcating the spirit of Jihad [clearly meaning war in this sense] continued. The national curriculum directive in 2002 maintained that, "the sense be created among students that they are members of the Islamic Millat. Therefore, in accordance with the Islamic tradition, they ought to develop into true, honest patriot, servant of the people and Janbaz Mujahid [life giving warrior] in his heart."

In higher classes, especially during and after the rule of General Zia-ul-Haq Jihad was unabashedly promoted. A curriculum document from 1986 noted that students, ‘Must be aware of the blessings of Jihad, and must create yearning for Jihad.’ With such a clear promotion of Jihad against the ‘enemy,’ especially as one of the highest levels of service to the nation, anti-India sentiment has been clearly cemented in the school going youth of Pakistan over the past several decades.

Pakistan’s perception of India is also tied to the Kashmir dispute. In a way, it is the Kashmir dispute which prevents Pakistan, and to an extent India, to move beyond 1947. The ‘unfinished’ business of 1947 keeps the raison d’etre of Pakistan alive in the minds of the government and people of Pakistan and prevents a positive development of India’s perception.

As several scholars have pointed out, Pakistan has time and again used the Kashmir issue to forge national unity. In a country bereft with internal tensions between provinces, classes, etc., for decades, it was the Kashmir issue which brought all shades of opinion together in the country. Therefore, it was a very useful tool to create a sense of common cause against a ‘tyrant’ [India] which had been oppressing the Muslim majority region of Kashmir since 1947. Also, since the Kashmir dispute was tied to events of independence in August 1947, the massacres of the time--mainly blamed on the Hindus and Sikhs in Pakistan--were a continuous memory. Where the Sikhs were largely redeemed in the Pakistani mindset after Operation Bluestar, the bulk of the responsibility for the 1947-8 massacres then fell on the Hindus, who of course inhabited ‘Hindu India.’

For a long time the virulent anti-India stance of the Pakistani media has also fuelled the negative perception of Pakistan. For decades the state run, Pakistan Television Network--till the early 2000s the main news and entertainment channel in Pakistan--aired a programme in prime time focusing on Indian ‘atrocities’ in Indian Kashmir.

Like conjoined, but estranged twins, Pakistan and India have also been tied together by an eternal comparison--more so in Pakistan than in India perhaps. Since Pakistan was the newer nation, it had to be more successful than India in order to prove its existence. When Pakistan performed better economically [for example in the 1960s] a number of Pakistanis saw it as ‘proof’ of the success of the Pakistani experiment. Writer Kamila Shamsie noted in a Guardian article: "At the start of the 90s when I was, bafflingly, taking A-level economics in Karachi, our teacher taught us all we needed to know about India’s protectionist economy with the sentence: ‘The only part of Indian cars which doesn’t make a noise is the horn."’

That India was economically worse off than Pakistan reflected well on Pakistan and gave its people confidence that the separation they achieved was worthwhile. However, the downturn in the Pakistani economy in the 2000s and the rapid development in India has given something to think about to Pakistanis.

As successful entrepreneur and Managing Director of Oxford University Press in Pakistan, Ameena Saiyid, noted to Kamila Shamsie, Pakistanis envy Indians when they refuse to allow ‘its cows and elephants and other religious symbols and beliefs to impede their march to economic growth while we have got totally entangled in our burqas and beards.’ Again, what Pakistan thinks of India is critically tied to what it thinks of itself and what is happening in the country.