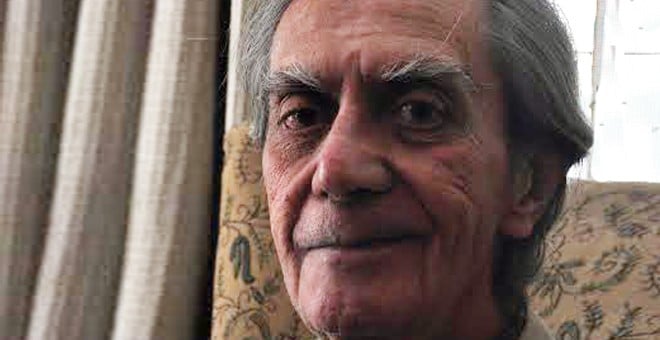

Aslam Azhar walks down the memory lane of PTV’s past 50 years

The urge to teach by instilling doubt and a courage to say ‘No’ in thunder has been a project of countless authors. There are two tiers of didactic literature: first, in which artists present problems and/or solutions reductively, with a vehement advocacy for a position on an issue which, in itself, does not impinge on a broader philosophical outlook; and second, one in which artists try to teach by undermining confidence in a certain way of viewing the world and encouraging a reconsideration of values on a broad scale. Admittedly, the two will often overlap. Aslam Azhar descends from time to time to the first, but overall his work belongs to the second.

Born in September 1932 in Lahore, he earned a Masters Degree in Law from Cambridge before joining Burmah Oil Company in Chittagong. He resigned in 1960, came to Karachi, and began to make documentaries for the Department of Films and Publications, Government of Pakistan.

In 1964, he teemed up with the Japanese on a pilot project to set up the first television service in Pakistan starting out in Lahore. He became its Managing Director, the post he was forced to relinquish by Ziaul Haq. In December 1988, when Benazir Bhutto’s first tenure started, he became Chairman of Pakistan Television and Broadcasting Corporation - the service that lasted only twenty months. Since then, he’s lived a life of retirement in Islamabad, reading books and "wishing for a happier country to live in." Below are excerpts from an interview:

The News on Sunday: What were the terms of your engagement with PTV, with an academic background in law and jurisprudence from Cambridge University?

Aslam Azhar: When I got back to Pakistan from Cambridge in 1954, there was a lot of talk in the air about the need for a television service. Upon my return, British companies initially employed me as a sales executive, which was the most unexciting profession. As we say in Urdu: "Parhain Farsi aur bechain tel". I didn’t stay long and became a freelance. I moved to Karachi, and with my background in documentary filmmaking and theatre, began to continue making films. It was there that NEC (Nippon Electric Company) of Japan found out about me and my background in theatre and radio broadcasting, and contacted me through their team leader, Mr Inoue, who became a good friend of mine afterwards. I came on board. Once I became the Programme Manager of the pilot station in Lahore, I was given a free hand because nobody else knew anything about television.

Very quickly our pilot station began to flourish. We got the best musicians, classical and folk alike, and best writers of stage and theatre who started working for us. In fact, one of my biggest contributions to the culture of Pakistan was the introduction of our folk musicians onscreen. Their voices had been heard on radio but they’d never been seen. With vocalists like Saeen Marna -- the great folk balladeer -- and instrumentalists like Ustad Sharif Khan Poonchhwale, we became a rich programme mix from the very early days.

As the programme grew I grew with it. We were so successful that the then Secretary Information from the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, the brilliant civil servant, Altaf Gauhar, picked me up and said: "Now you come over to Rawalpindi. You started the Lahore station and it’s doing very well." I had a very good team -- young men that I had handpicked from the National College of Arts, Lahore, and from other places; we had good producers, first class cameramen and ace designers. I moved to Rawalpindi where the ministry had its offices in Chaklala to set up another pilot station. It took off and must have run very successfully for a couple of years when the government began to dream of a television station in Karachi.

TNS: What was the initial agitprop or agenda?

AA: I set up the first tv station in Karachi which was custom-built as a proper studio for television. It had a proper office and an efficient team, and OB Vans (Outside Broadcast Vans). Every telecast was ‘live’ -- we had no recording equipment at that time in the pilot stage. Mr Z A Bhutto picked me up and made me its Managing Director. Artistes like Reshma and Tufail Niazi, and writers like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Sufi Tabassum, Safdar Mir, Kamal Ahmed Rizvi, Ashfaque Ahmed, Dr Enver Sajjad and Bano Qudsia became strong supporters and contributed scripts. Uxi Mufti was one of my regular talents in Rawalpindi who used to host an arts programme on folk artistes. I made a lot of effort to get music talent from Dhaka, such as Abdul Haleem with a voice that came from the chest, Firdousi Begum, Runa Laila and Shehnaz Begum. I called over a team of producers from Dhaka such as Zaman Ali Khan, Mohsin Ali, Shehzad Ali and Shahzad Khalil.

We did a lot of experimentation with folk and classical singers new to the television. It was my big contribution to bring the folk culture to the screen. I believe if we can’t take our plays to the rural areas, we’ll bring the rural areas into our plays. That was very much part of my conscious endeavours to bridge the gap. The writers writing for us would depict the ordinary people; no celebrities, no film stars, and no elite. We did plays by the people and for the people.

I made a conscious effort to be ‘correct’ about the language spoken on television. I was very particular with my boys and girls that whenever they speak they should do justice to the language and speak comprehensively. For instance, the credit of introducing the term ‘Nazreen’ (viewers) goes to PTV. ‘Sama’een’ (listeners), however, could be heard on Radio Pakistan.

TNS: What role did Government College play in providing you a baseline for your future involvement with the dramatics?

AA: Government College, Lahore, was a culturally rich institution. It was here that I started my career in theatre. Rafi Peer was a great institution of Lahore unto himself in those days. I invited him to the college, and in the staffroom gathered all the senior students who were interested in theatre along with a number of professors and lecturers. Rafi Peer gave a very inspiring talk. Before that, at home, both my parents encouraged cultural activities, and we had a very congenial atmosphere. I was able to pursue my interests without anyone looking over my shoulder. I did a lot of live broadcasting of sports events and drama on Radio Pakistan.

We chose to do social drama onstage as opposed to political drama, apart from family drama and comedy for GCDC (Government College’s Dramatics Club). In addition, we did translations, such as Ibsen’s The Wild Duck and Hedda Gabler, and Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard. Then we did Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and Samuel A Taylor’s The Pleasure of his Company.

Fareed Ahmed who was fondly called Sami by us, was younger than me at Government College. His father W. Z. Ahmed was a top film producer in Lahore in those days. Sami had inherited his father’s talent and did a lot of remarkable ‘things’ for us, such as Terence Rattigan’s While the Sun Shines onstage. He acted, directed and produced the play. I was also the elected member of Government College’s Student Union’s Debating Society.

TNS: It appears that the idea behind the inception of KATS was to ‘reach out’. How did it help reach out to the ordinaire?

AA: I had two or three very encouraging professors at Government College under whose influence I started doing theatre, step by step. When people ask me where did I study theatre, I say, "On the job; by doing it!" I used to say, "There’s no Masters Degree in theatre -- you learn it by doing it onstage." And that’s where I learnt my theatre art. I used to say to my younger producers: "When you watch cinema, film or a television play, your eyes are taking in the story but somebody else is doing the digesting for you namely the writer and the producer. You’re simply taking it in. But theatre is different -- theatre audience and the actors onstage are one team producing an event. This is the great creative difference between theatre, on the one hand, and television and film, on the other. The audience’s reaction makes you act even better.

While in Karachi, Sania Saeed’s father Mansoor Saeed -- a passionate theatre person -- along with a couple of other people and I got together and decided to set up a little theatrical society or company, thus Karachi Arts Theatre Society (KATS). We gave it the name Dastak. We went knocking on the doors of people’s minds and saying open your eyes, there’s more to life than what you’ve imagined so far. It was founded in 1960. At that point we used to do plays in English. KATS is where I met my future wife, Nasreen Jan.

We got together a group of like-minded people, including students from Dow Medical College, and started doing theatre on social themes. Mansoor Saeed was a great translator who had joined us. It was on Labour Day that we decided to take our play to the industrial area of Korangi where we set up a stage in the wide street with a factory on the right, a factory on the left and a factory at the back.

Around five thousand workers sat on the ground in front of us and watched us perform with whatever lights we had, and when the lights went out, somebody put on the headlights of his car. When this happened, I called out to the audience, "Bus ab khatam karein!" and it shouted back, "Naheen, naheen, jaari rakho!" That was, of course, a tremendous experience for us. It was on the occasion of centenary celebrations in 1986. Before that, we’d done Brecht’s Exemption and the Rule on a rooftop to a group of factory workers.

Then we did Saint Joan of the Stockyards and Life of Galileo, both by Bertolt Brecht during Ziaul Haq’s time. It was a period of strict censorship, and the plays were about anti-religious fanaticism -- about how the church opposed scientific thought, etc. I acted out the part of Galileo and also directed the play. It was staged to all kinds of audiences -- in theatre as well as in Hashoo Auditorium, with a 3-night re-run for the India/Pakistan Progressive Writers’ Conference.

I remember adapting Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar into Urdu for the television on September 5th in 1965. The very next morning war broke out between India and Pakistan. It was a costume drama in which I played the character of Brutus.

TNS: Where do you think PTV is heading now?

AA: When we started out, the society was not ruled by the cultured few but had a heavy presence of very highly cultivated people -- writers, singers, actors, comperes, and so on. Now we are a consumer society. Therefore, our television reflects that, as it must, as it should because television must always be true to life around it. So what you see on television is what you are experiencing in society, in life.

When Ziaul Haq came into power, he imposed his own ‘culture’ on television itself and radio, and on society. But I must say that the PTV cadre maintained its character. They had their own value systems too and they stuck with them throughout. When I came back they were ready to move ahead. They had not been infected. I held a programme called Music ‘89 that was hailed as a breath of fresh air.