The cycle of betrayal, broken promises, and of producing more powerless by the powerful is not likely to end till the social equaliser of education is made available to every child in Pakistan

A thinking person’s lunatic proposition, great innovations and inventive public policy initiatives, all have a commonality: In the beginning they all look odd, impossible and thus unacceptable. The biggest resistance to new ideas comes from two groups; the most ignorant and those who have a stake in the status quo of chaos and crisis.

Iqbal may have this in mind when he wrote: Aain-e-nau se darna, tarz-e-kuhn pe urrna/ manzil yahi kathun hai, qaumon k zindagi mein (Fear of the new ways, sticking to the old course/perhaps this is the impediment in the progress of nations). But Iqbal had the ignorant group in mind, not the ones who have by design become a bottleneck in Pakistan’s way to progress.

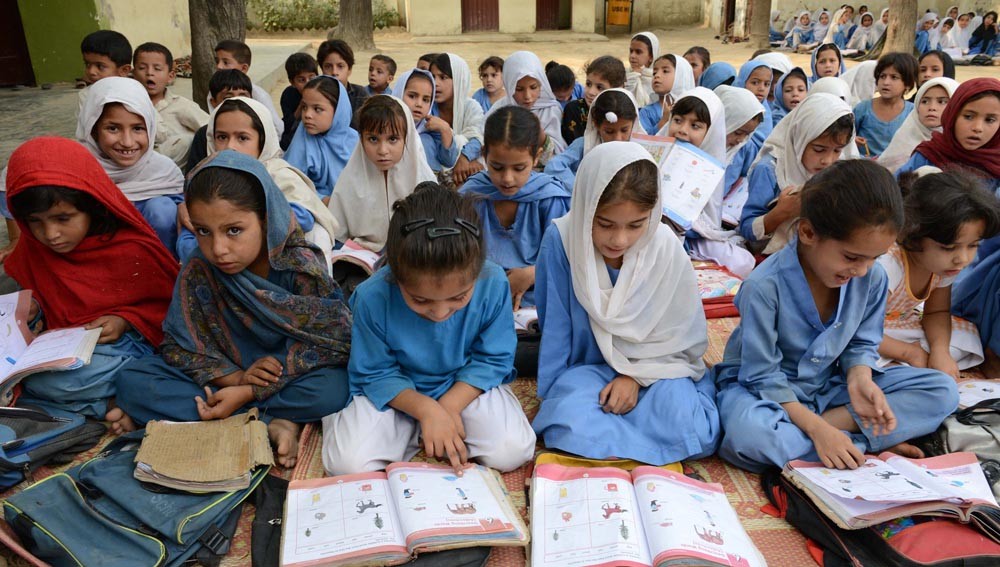

A recent report on education ‘25 Million Broken Promises’ by Alif Ailaan, a campaign targeting increased enrollment, retention and learning in schools, is full of painful and inconvenient truths. It manifests how brazenly the powerful in Pakistan are failing the children of the powerless. It seems all of the powerless in Pakistan today are the children of yesteryears who were failed by the predecessors of today’s powerful. The cycle of betrayal, broken promises, and of producing more powerless by the powerful is not likely to end till the social equalizer of education is made available to every child in Pakistan. The crisis of education has emanated from a failure of imagination on the part of the ruling elite, in particular the politicians.

There are many countries that have attained 100 per cent literacy and universal elementary education; and Pakistan is not even in the first 100 of that ranking. Whereas, only 9 countries have made nuclear weapons; and Pakistan is one of them. The nuclear target was realised due to collective resolve of the ruling elite of Pakistan. It’s time to make education transformation the next nuclear ambition of Pakistan.

But any ambition needs a long-term plan and committed human and financial resources. On education, I say, education for all will only be possible when all (those who matter) are for education. And at that, one education for all is must if we want a society of equals. The current divergent and at times conflicting streams of education are producing citizens who even do not want to bear the other’s existence, let alone their peaceful coexistence and affable interactions.

Here is how it can happen; politically, administratively and technically. Since a detailed strategy or a transformation plan cannot be summed up in the allowed length of an opinion piece, the gist of the plan may seem sketchy. But then an opinion piece is not a call to revolution. The best it can do is to trigger a meaningful and new conversation leading to a possible solution.

Also read: State, education and citizens

Politically, one education for all design will require ‘a recentralisation of resolve matched by a decentralisation of delivery.’ Administratively, doing more of the same won’t get us anywhere new, hence we need to take some bold and innovative steps (discussed below). Technically, we need to redesign schooling, learning and teaching which are compatible with the 21st century. This plan will help us reach a fresh future, instead of dragging us back to the stale and sorry past.

The post-18th Amendment successor of the erstwhile Ministry of Education hosts a forum called ‘Inter-provincial Education Ministers Conference’ (IPEMC), which in my view is the right forum to deliberate over this proposal. That will take care of any implications in the ‘recentralisation of resolve’ which may be interpreted as contrary to the spirit of the 18th Amendment.

The first requirement towards OEFA is to have an accurate statistical picture. Currently, there are two major blind spots and data is either controversial or incorrect. One, the number of children who need schooling varies depending on how one calculates, and given that the last census occurred in 1998, the population projections are also speculative. Two, when we talk about education financing, we only have official allocations in view. We have no idea of the total social spending that Pakistanis make on educating children.

To have an idea of total social investments, we need to include the costs of public and private infrastructure, the salaries of all the teachers, fees of all kids, the transportation expenses of all children, the costs of tuition; and the annual social costs we incur as a country and society by not having invested timely in the education of our children; that is the costs of not investing.

This statistical picture can be had by adding a few more, education related questions in the next census; and holding the next census, as soon as it is manageable.

Once we know the answer of how many kids need schooling in the next ten years, and what is their social and geographical location; gender, and special needs, we shall be able to calculate how much finances we need to put all of them in schools, keeping them there till they complete secondary schooling, and ensuring they have acquired sufficient learning for further journey in education, skill acquisition and or gainful role in the national labour force. Let me reiterate here one critical point: they all must go to similar schools with same socio-physical infrastructure, interact with similar learning tools and contents, and are imparted similar ethical values.

To achieve this, the government needs to deliberate the following four broad reforms.

Merging the redefined ‘public’ and the ‘private’

The state/governments shall only fund the education promised in the Article 25A; but must not directly manage a school, or teacher, or a principle. The management should be handed over to those with demonstrated experience, commitment and passion for education of children who are not their own.

The new managers will be subjected to two types of supervision: One, by the authority that releases funds that are linked to the results; and, two, in governance, by people specifically elected for education oversight. It means all the schools that are in the private sector, and private buildings will move to the public schools. As the place and space of the public sector converges with the face and pace of the private sector, we shall see a significant change.

Mainstreaming the technology in the entire spectrum of educational provision

Today, technology has made life and many of the challenges far easier than they were say 10 years ago. The intelligent deployment of telephony, internet and web-based technologies can help improve all aspects of education without negatively displacing the labour force or compromising the quality of learning.

In practical terms, it implies infusion of the technology in all arenas of education -- planning, provision, allocation, spending, management, monitoring; the teaching and the text; and assessment and learning, et al. The involvement of technology will require new pedagogy, newly-trained teachers, new social and political attitudes to schooling and new structures, mechanisms and procedures.

Separating provision, supervision and regulation

Our experience tells that the regulators, the providers and the monitors should not be the same entity. In practical terms, this will entail radical steps. The redesigned departments of education will perform two functions viz. education financing tied to results, and enforcement of regulation to ensure the minimum standards of service provision and learning outcomes are met.

Creation of regional education authorities based on sub-national languages

The provision of one education for all will be dispensed by citizen-led, regional education authorities, and the regions should be carved out based on sub-national languages (Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Seraiki and Balochi, et al). This implies early education for all in their mother tongue or in the language spoken the most in a household (if it’s a multilingual household). This will trigger a local social economy related to the local language.

These four steps will require a transition of 3-5 years to redesign one education for all children, at much lower costs and to far greater satisfaction. The rest, as they say, is a cakewalk.