Originalism requires an engagement with, and the development of the discipline of, history and particularly legal history

My piece last week regarding the importance of engagement with Originalist strands in Islam has made many people ask me highly pertinent questions.

Maybe it was the inflation of judicial activism in Pakistan in recent years, particularly under former CJP Iftikhar Chaudhry, that fuelled my interest in judicial conservatism. As I said last week, Originalism is just one strand of conservatism. All conservatives are not originalists but almost all originalists are conservatives.

Whether it’s scripture or a constitution, originalism presents certain pressing problems. How do we gauge ‘the’ original meaning? Do we try to gauge the intentions and practices of the authors of the relevant text or do we look at how common people (ie. largest consumers of relevant text) understood it at the time. Even the different strands of originalism do not agree on this. But does that mean that originalism is nothing but conveniently read/interpreted history?

Some might strongly argue that this is the case but problems of interpretation remain equally relevant to liberal schools of thought. Interpretation, liberal or conservative, remains a fundamentally human exercise. The most relevant questions are: what weight do we attach to the different factors impacting interpretation (for instance history, numbers or consensus today) and do we care more about outcomes or approaches?

A conservative approach can lead to an essentially liberal outcome. While activism and theories of ‘living breathing’ constitution do not reduce in any way the chances of outcomes damaging to the system.

The classic examples in the domain of law arise in cases concerning unlawful detentions, searches and military coups. A conservative judge interested in the original context of a constitutional provision that guarantees security against unlawful arrest/detention is likely to rule in a way that leads to liberal outcomes. And living breathing constitution theorists can damage continuity. If everything is up for evolution with time then ‘necessity’ assumes a weight it otherwise wouldn’t with a conservative jurist. This is not necessarily a bad thing.

However, if we support an evolving meaning of scriptural or legal texts, are we not banking on the fact that only those who have egalitarian aims favouring the general public (or even particular sections of it) will come to power? This calculus can go horribly wrong. And there are clear examples of this within Pakistan too -- each military coup was justified by a court ruling that focused on evolving political developments.

Pakistan has seen its share of judicial activism on both sides -- validation of military coups as well as attempts to make the apex court relevant to the lives of the people. The living breathing ideology may take a flattering view of the constitution but it inflicts a much bigger casualty by leaving the interpreters (judges) unaccountable. This brings us back to the same point as earlier. What is the way out if a reductionist school of thought gains ascendancy? We can’t vote judges out (in most democracies) so should we trust an instinct that we can’t do anything to change?

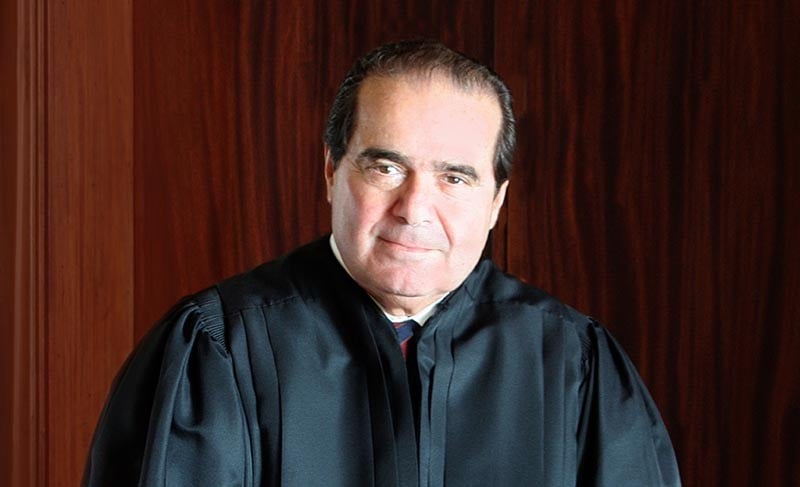

The pushback would, of course, be that what can we do about originalism if its proponents decide to spoil the party? That is a legitimate query and deserves serious engagement. However, we don’t have a choice to ignore the original text and its meaning as originally understood/applied. This may not always yield the right answer but the scope of the inquiry is not as uncontrolled as those who believe that the constitution is a ‘living breathing’ document. If you believe in an evolving meaning then, as Justice Scalia says, you’re basically looking up at the ceiling while twiddling your thumbs and asking, "has the meaning changed yet?".

None of these arguments (whether for or against originalist readings of the constitution in Pakistan) are ‘clinchers’. They are not dispositive of the issue by the force of their logic. But Pakistan has never actually engaged with originalism when it comes to the constitution. Apart from a limited number of years at the beginning when judges and lawyers were interested in what the framers meant or had in mind, the bulk of our constitutional law history is filled with talk of the ‘living breathing’ constitution.

This doesn’t mean that the theory doesn’t hold water. But abandoning all engagement with the constitution as an enduring document (rather than an evolving one) is also more convenient -- to lawyers as well as Judges. Originalism requires an engagement with, and the development of the discipline of, history and particularly legal history.

Competing visions of the constitution, its interpretation and meaning are likely to be an aid rather than hindrance to policy making and our development as a society. In the US, for instance, originalism started out strongly but almost died for about two decades till Justice Scalia and other like-minded lawyers/academics revived it.

All conservatives agree on the basic premise that the task of the judiciary is to say what the law is, not what it should be. Owing to Pakistani public’s obsession with blaming civilian corruption as the greatest evil, we have not always stressed this. We celebrated as the judiciary legitimised military coups and threw out elected civilian leaders.

The superior judiciary, in recent times, has done a commendable job of trying to fashion a new approach. It faces the baggage of its history but it is carving out a place for itself. Schools of constitutional interpretation should compete for ascendancy at this stage in our history to ensure that the judiciary receives all possible perspectives from the bar and academia.

One can only hope that the Pakistani public and intellectuals will give originalism the chance that it deserves.