Of ‘terrorist’ Baloch and ‘Afghan emigrant’ Pakhtuns, and all the old rhetoric about what ails Balochistan

For a discerning visitor to Quetta, the capital city of Balochistan, just a day or two, not months, is enough to convey a deep sense of alienation and hatred of local people against the central government.

Walk in any market place, a street inhabited by Pakhtuns, the Baloch or Hazara tribes or visit a public sector organistion and you notice that the basic causes triggering anti-Pakistan sentiments amongst the Baloch still exist with no remedy in sight.

Spectres of fear, deaths, kidnappings and torture hover over the city. On the other side, besides plain mismanagement, bad roads, absent pavements, choked vehicular traffic, no sewerage system, and long hours of power loadshedding are a common sight.

But this is one part of Quetta where local Pakhtun, Baloch and Hazara tribes are living. Fortunately, the city is also home to a big cantonment, spread over miles, completely different from the rest of the city.

"An island of luxuries in the midst of a sea of miseries," is how Dr Faizullah Jan, an academic from Peshawar University, describes the area. "Here roads are wide open, dressed up in extensive pavements with streetlights, markets are well-lit at nights and couples do night walks without any fear of being killed or kidnapped."

However, this ‘island of luxury’ is out of the reach of the people of Balochistan. To enter the military cantonment, these ordinary mortals need to be in possession of ‘special permits’, not just the NIC -- the mere proof of Pakistani citizenship.

"Now we reach the Afghan border, ‘nay the Indian border’," says a driver who picked us from the airport for Lourdes Hotel as he reached the check point at the start of cantonment area.

"Now questions like ‘from where you came? Where are you going? Where were you born?’ will be asked," the taxi driver keeps murmuring while searching for identification documents in the car’s dash board to be produced to, what he said, "border security guards."

These were not just exhortation of an angry taxi driver -- complaining against the attitude of security people. The next day returning from Balochistan University in the personal car of a lecturer, similar words were spontaneously uttered by our lecturer-cum-driver.

"He [taxi driver] was right. To enter cantonment area local people need special documents -- passport, besides undergoing tough questioning," says the lecturer.

Also read: Quetta -- a segregated city

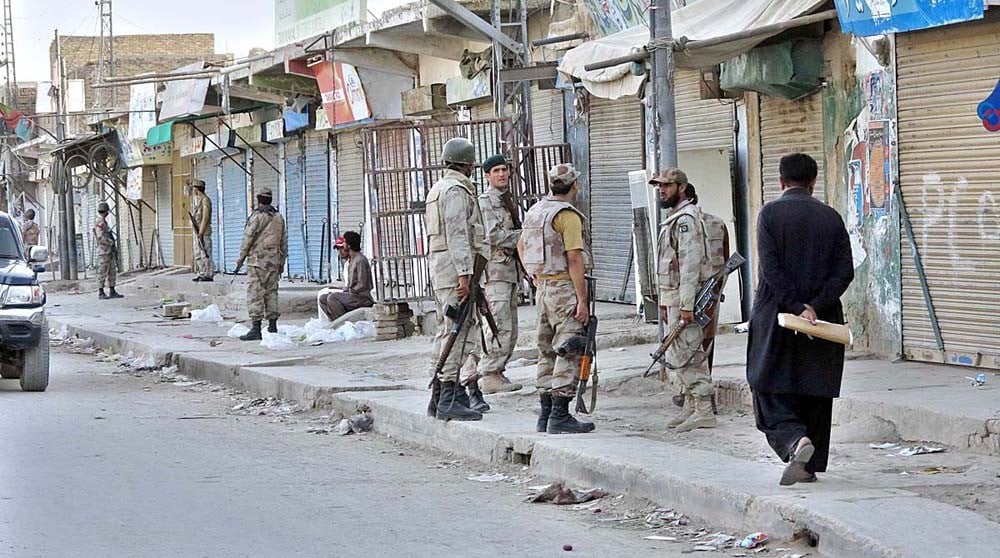

The fear-inducing stern looks of the security men give an impression that Quetta is really a hard place to live. Strangely, everywhere, the mere sight of men from Frontier Corps or military is enough to evoke rebuke and condemnation for Pakistan. "Military men keep staring at everybody just because everybody here is a suspect."

There is a sense of alienation among the local population. Besides holding important positions in public sector organisations, the settlers also enjoy sway over the narratives vis a vis Baloch and Pakhtun ethnicities.

As one walks around in markets and government offices one gets an impression as if majority of the Pakhtuns in Quetta [read Balochistan] are ‘Afghan emigrants’ and majority of Baloch are ‘terrorists’ and anti-Pakistan.

"National Identity Cards (NIC) are ready for the Afghans, prior to leaving Afghanistan and crossing the border over to Pakistan," a senior university academic, himself a settler, says with authority.

Of the Baloch problem -- as we hear in Islamabad -- one can hear the same wisecracks in Quetta: "The Baloch problem is created by few Sardars, not by the government." This narrative is as common in Quetta as in Islamabad or Lahore, particularly amongst the predominantly settler community in government offices or university faculties.

"The Baloch are wrong in blaming Islamabad for their problems; their Sardars are responsible for keeping them poor and ignorant," says a senior faculty member at Balochistan University in Quetta.

In Islamabad as in rest of the country, one overhears that Pakistan’s flag can’t be strung up at flagpoles at schools nor did national anthem play in suburbs of the province. But if truth be told, the situation is more than critical. As told by a number of faculty members of the Balochistan University no teacher can even name ‘Pakistan’ or ‘Pakistan army’ in class lectures. Remember University of Balochistan is in Quetta, not a suburb town.

"I had to refuse teaching ‘Constitution of Pakistan’ in my class after being threatened by one of my Baloch female students," says a faculty member at Balochistan University.

"Every time I started my lecture on ‘Constitution of Pakistan’ a (female) student in classroom would show me her bangles that had BLA flag’s colours," he says. He says he called the student to his office and tried to convince her that he is just teaching the course and had nothing to do with current politics but she advised [read threat] otherwise.

Another female faculty member shares identical views. During class lectures, this teacher from Karachi says, faculty members avoid referring to something or even taking example from Pakistani politics. "The mere mention of Pakistan or Pakistan army is inviting wrath of the Baloch students. On the other hand the mention of ‘mutilated bodies’ annoys the ‘other’ [referring to intelligence guys] in the class that is putting you in trouble," she said.

In Balochistan, expectations were raised when Dr Malik Baloch-led Pakhtun and Baloch nationalists’ political parties took over the provincial administration following May 2013 elections. The nationalists’ regime has, however, done too little to be counted in alleviating the prevalent sense of alienation or deprivation. The regime is stated to be powerless and accused of maintaining the status quo of the past.

"It’s a total disappointment," says Ali Khan, a senior journalist working for national broadcast. "Nothing has changed since [Baloch and Pakhtun] nationalists took over the administration. They have yet to come up with a plan to address some basic issues like law and order, corruption and target killing."

"Not a single gang of target killers or those involve in sectarian massacre have been busted. Except postings and transfers, Dr Malik’s administration has no authority," says the journalist.

After sunset, most of the city becomes virtually a no-go area. "Even the security men avoid visiting the Baloch populated areas when it gets dark," says Aurangzeb Kasi, central secretary general of Awami National Party (Wali).

A university professor, pointing his finger to Saryab Road in front of the University, says, "From here up to Karachi is all no-go-area for us." There is complete chaos and the administrative vacuum is leaving too much space for the gangs to rule streets in Quetta.