Today the audience is expected to see not Bond’s sins but his style

Many years ago, when I was a more sociable person, I was once made to sit next to a retired banker at a charity dinner in Putney. In between the starter and the main course he turned to me and said, "Short name -- long bladder. Do you know what that means?" "No", I said, "I’m sorry I have no idea what that means. It sounds like the punch line from a Bond movie". The writer of Bond movies usually wrote such cryptic two or three words for Bond to say when he scored a point off his adversaries.

My fellow guest leaned closer to me and said, confidentially, "I have found out that this obscure saying is apparently a reference to the peculiarly Icelandic habit of writing your name in the snow as you spend a penny," He laughed triumphantly and added, "This is one catchphrase Bond wouldn’t know anything about."

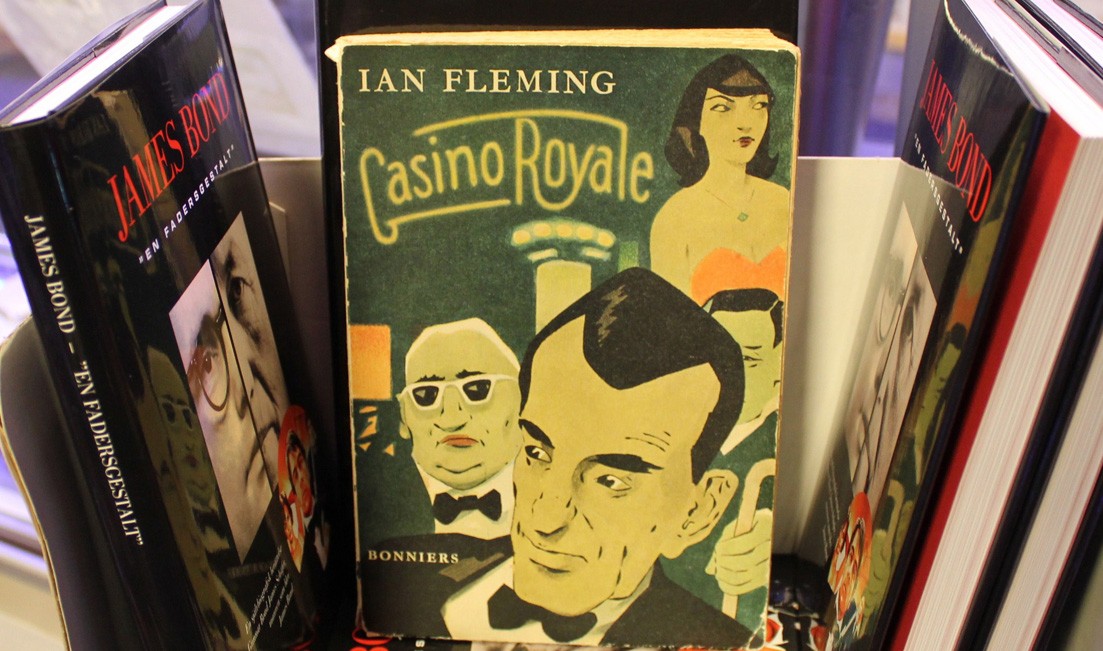

This was the time when Bond movies had become a cult and the latest release Casino Royale had been proudly proclaimed by the producers as the costliest movie ever made. Naturally, no one could afford to miss a film that had cost seven and a half million dollars, an astronomical sum in those days. Money begot money and a rather poor film earned more than any other film ever made.

I am talking about the era of mini-skirts. Mock, burlesqued Bond-type thriller became one of the biggest industries. It was the fantasy fare of the world and it replaced the lush, plush Hollywood musical.

What was this appetite for? It wasn’t anything Ian Fleming intended to supply when he wrote Casino Royale in 1952. How could the loyal public school boy, a direct descendant of Graham Greene and Eric Ambler’s protagonists become the culture-hero of millions? How could a typically Western concept, rooted in cold-war journalese, turn into an idol of Arab children, Calcutta clerks and Panamanian Peasants?

Perhaps the key is to ignore the source and look at the final product -- the day dreams themselves. Is it not a fact that the makers of these films adopted the Bond saga to an older legend -- the Arabian nights? Each of the Bond stories was pushed so that the mixture of sex, cruelty and wonder remained intact, but technology substituted magic.

Thunderball was the perfect example where mechanical toys and gadgets replaced all the original magical instruments the hero had at his command in an Arabian Nights tale: rockets for winged horses, blimps for flying carpets. And the scene in which Bond was given these miracle gadgets exactly paralleled Aladdin’s fitting out with ring and lamp.

The vaults of the Fort Knox (Golfinger) were but a modern equivalent of Ali Baba’s cave. That was not all. The ever present ingredients were kept intact: the evil enchanter, the captive princess, the soulless siren, the resourceful, cunning hero. Anyone who has ever read the Arabian Nights tales could recognise these characters.

The imagery of each of these films had been reduced to almost as basic as that of the comic strips. Bond leaping into the sky, Batman landing on top of eleven villains, had more in common with Mandrake and Flash Gardon than with the seedy, puzzled characters of John Le Carre.

The amazing coincidence was that the popularising of the technique was just what the "in" artistic people were enthusiastic about. They had a tremendous soft corner for comic strip heroes. Mandrake, the magician, became the most fashionable cult of the new wave directors. Its influence could be seen in such trend-setting films as Juleet Jim, Tom Jones and so on. What you saw in those films were jump cuts, frozen frames and images just as you saw in other films interpolating legends reading "Meanwhile…"

This influence was largely due to the relatively unknown fact of cinema’s economic life. The majority of young English and American directors cut their teeth on advertising films for cinemas and television. Now, what the advertisers wanted was the shortest possible transition from the image of need to the image of the brand name. The technique of the commercial was the jump cut from wish to fulfilment. It now became the technique of the new international pop cinema. Speed eliminated the time for guilt, pity, or considering the implications.

There was no time to see the blood flow, the skin writhe. It was all a huge joke. Illicit impulses and aggression could be enjoyed without pausing to recognise them. In any case they would be camouflaged by the masquerade under the general licence of swift-paced parody.

All of this was a few decades ago. Today the filmmaker in the West goes for something funky. The hero now is a bad boy prone to dissent and violence. The audience is expected to see not his sins but his style.

This is the smart young mood of today; being bloody is being authentic. And those who disapprove or shudder and turn away from the heroic sins are not supposed to be in the flow of contemporary reality. The blockbuster films of today are soaked in blood, with the impact of bullet on the flesh, with the fear of imminent death with agonised writhings.

Carnage is almost vital ingredient. Fast and Furious, Die Hard, Transporter (and their sequels) are seen week after week on most of the movie channels. The explicitness of the violence would have overwhelmed the lover of Bond movies. It’s as though violence was the one and only many splendored thing the film-makers as well as their young audience wish to celebrate and admire.

In America big movies open on thousands of screens across the country and if they survive the first weekend they are regarded as a success. The initial audience consists largely of eighteen to twenty year old males, the section of society most drawn to violence. The surest way to make a splash is to stimulate and exploit these youngsters with graphic, frequent and sexy violence.

Sad, though it may be, it is also a fact that the American predilection exports equally well. Take Terminator or Man of Steel, violence and its accessories of muscles and guns and other outlandish weapons have become as commonplace in Kentucky as in Karachi. It is now a part of the global culture. Bloodshed exhilarates in Amsterdam or Amman as surely as in Ahmedabad. You would have to be exceedingly naïve if you don’t acknowledge the connection between the screen and the world. It’s no use expressing your horror over the slaughtering of human beings in public; in Iraq or Libya. It has already been depicted quite vividly in the blood-soaked Western -- and in its wake -- Eastern movies.