A new vista for academia to re-interpret Islamic teachings

(III)

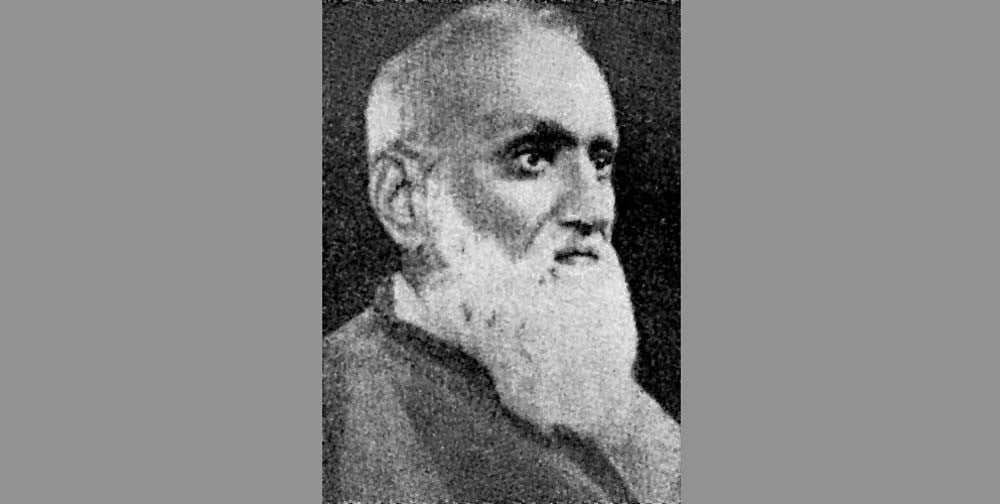

Renowned historian Aziz Ahmed credits pan-Islamist Ubaidullah Sindhi as "the only political thinker of any considerable calibre to come directly in contact with Russian communism at an early stage". He epitomised the plural character that characterised the Ghadar Movement, of which he became a member in 1926.

Born in a Sikh household in Sialkot in 1872, Ubaidullah attended school at Jampur where his maternal uncle lived. It is said that books like Tufatul Hind, Taqwiyatul Eeman and Ahwaal ul Aakhira instilled in him an interest in Islam, leading eventually to his conversion in 1887. In the same year, he went to Sindh where, as Sara Ansari notes, "pirs in Sind became more conscious of the Pan-Islamic sentiment which had been stoked by the decline of Turkey as an important world power".

Thus a number of Sindhi pirs forged close links with Pan-Islamists in other parts of India, most notably with Deobandi Ulema.

Sindh provided a conducive atmosphere for Ubaidullah’s religious instruction, particularly Bharchundi, which was reputed to be an important centre of religious learning. Here, he was taught by Hafiz Muhammad Sadiq. It was from Bharchundi that he went to Deoband for the first time in 1889. At Deoband, it seems he cast as much influence on his teachers and colleagues as they did on him.

In 1891, he graduated from Darul Uloom Deoband and went to Sukkur where he took up teaching under Taj Mahmood Amroti, who became his mentor after the demise of Maulana Sadiq. In 1901, he established the Darul Irshad in Goth Peer Jhanda. He returned to Delhi in 1909, at the behest of his teacher Mehmud-ul-Hasan, and founded Jamayat-ul-Ansar which the Silk Letters report suggested "may be called the Deoband Old Boys’ Association".

Read the first part: Revolutionaries from a century ago

In 1912, he took over a "Deobandi affiliate in Delhi" where he pleaded for synthesis of Aligarh’s modernism and Deoband’s traditionalism, and therefore not only introduced English-educated instructors but also put into circulation newspapers with advanced political views. In 1911-12, he vociferously propagated Pan-Islamic sentiment when Balkan wars were being waged.

Far too political for the Deoband high command, he had to resign in 1913 and founded his own madrassa in Delhi, the Nizarat al-Mu’arif. He now began to toe a militant line in his teaching and his books Talim-i-Quran and Khalid-i-Quran published in 1914 and 1915 respectively clearly elucidated Sindhi’s militant streak. It is pertinent that Sindhi’s social thoughts were anchored in the work of Shah Waliullah, who figures conspicuously in the genealogy of Deoband.

In June 1915, Sindhi covertly established a network of contacts among the frontier tribes throughout Sindh and the Peshawar district with the aim of kindling an insurgency in North West Frontier and the tribal areas. He then travelled to Kabul in October 1915, where he joined up with Lahore students and the Turco-German sponsored Berlin-India Committee mission.

In his capacity as home minister of an Indian government-in-exile, he tried to pursue his Pan-Islamic aims, but the Arab uprising in 1916 forced Ubaidullah to move in a more nationalist direction. He was convinced that the interests of Indian Muslims could best be served by forging a sense of Indian Muslim identity, instead of seeking cultural authenticity and religious guidance. He asserted that Indian Muslims ought to strengthen their ties with Indians from other communities through shared economic interests.

While in Kabul, Ubaidullah observed with great interest what was unfolding in Russia. Among his comrades was Muhammad Shafiq, later to be the Secretary of the Indian Communist Committee in Tashkent. Shafiq, supported by the Bolsheviks and their allies, organised revolutionary propaganda in India, and linked it to Sindhi’s gang in Kabul.

Read the second part: Another pan Islamist Ghadarite

In 1919 during the Third Afghan War, Sindhi sent a public letter to his Indian compatriots urging them not to support the British Indian government, but rather to "kill the English in every possible way, don’t help them with men and money, and continue to destroy rails and telegraph wires".

While in Afghanistan, he also founded his own militia named Jundullah or Al-Jund al-Rabbaniya (the Armies of God). As Zaman states, it included English-educated Indian Muslims who had come to Afghanistan to pursue anti-British campaigns. But in 1919, the government-in-exile was dissolved under British diplomatic pressure. Ubaidullah stayed in Afghanistan for nearly seven years, leaving after the Third Anglo-Afghan War.

After this, Ubaidullah travelled extensively. He went to Turkey in 1923 and then to Mecca in 1927, staying there for two years. But before these destinations he undertook a sojourn to Russia, where he was accorded the status of a state guest. Here he studied the ideology of socialism and found many lacunae in it. He is reported to have debated with the Soviet high command trying to expound the veracity of Islam, as opposed to communism, which he argued was merely "a reaction to oppression".

Despite his criticism of the material foundations of the Soviet system, Sindhi’s own thoughts regarding society’s decline were informed by socialism. The reasons for the decline of any society, according to Sindhi, founded on ideology (nazariyya) are two-fold. First, the concentration of wealth in the hands of a small elite and the impoverishment of the general populace, meaning that the masses are always busy making ends meet and lack the opportunity to attend to their moral/religious development. Second, the exclusion of the general population from knowledge of value to society, which is the sole preserve of the elite. This exclusion, Sindhi avers, leads ordinary people to suspect the moral foundations on which the community supposedly rests.

These thoughts of Sindhi, some scholars suggest, were gleaned from Shah Waliullah’s classic Hujjat Allah al-Baligha, but the socialistic ring that his discourse has imbibed can hardly be refuted. He returned to India in 1939 after a quarter of a century and began teaching Shah Waliullah’s books until his death in August 1944 in Lahore, where he had gone to visit his daughter.

There is an increasing interest in academia in the eventful life of Ubaidullah Sindhi and his attempts to re-interpret Islamic teachings in the light of the revolutionary currents of his own age.

One may hope that the academic circles of Pakistan too re-assess his role in history.