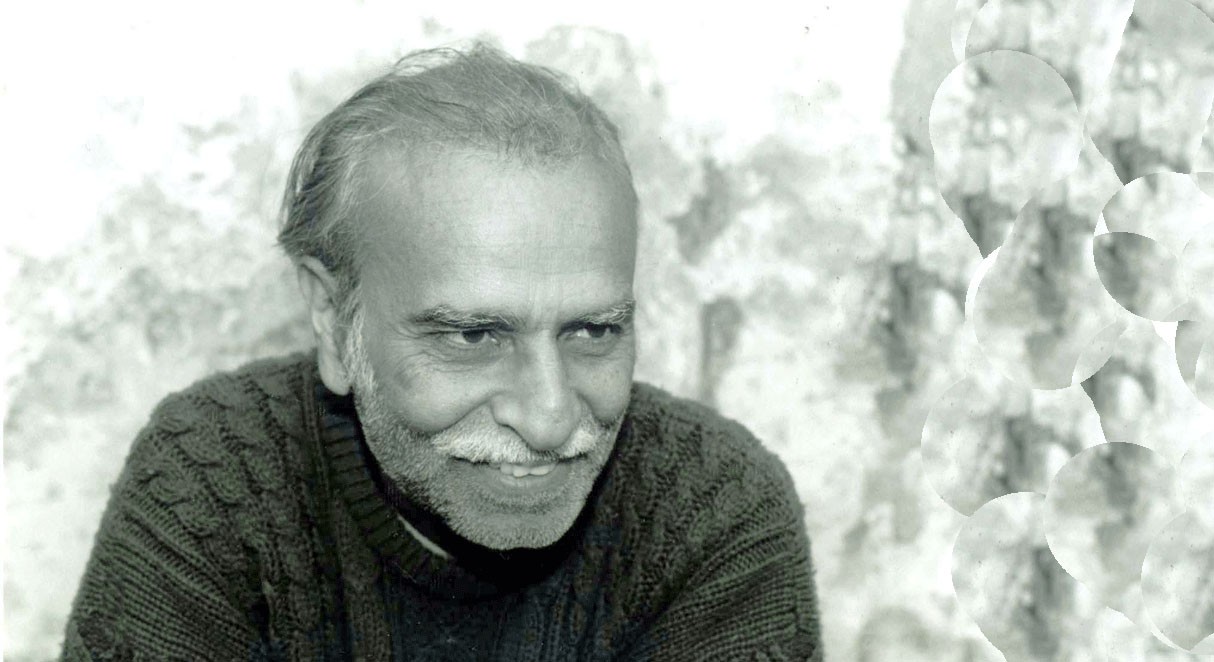

Najm Hosain Syed’s Sheesh Mahal Di Vaar -- a brief introduction

Najm Hosain Syed’s long poem Sheesh Mahal Di Vaar (History of the Sheesh Mahal) was first published in a book form under the same title along with other poems in 1993. It is a 26 pages long piece using four different voices in four different sections. In the poem, under the title, the following line appears in small letters and within brackets: (a buyer has developed apprehension regarding the debris of an old house in Lahore).

The poem can loosely be described as a meditation on the word parchawan which, lacking a precise translation in English, can be understood by a combination of the following words: reflection, image, shadow, shade, influence of evil spirit [as per Platts]. Along with parchawan, the meditation also has to deal with what we call vehm which can be understood as a combination of distrust, anxiety, fear, and superstition.

The first point of view is that of a businessman trying to convince a potential buyer. The next monologue comes from the mouth of an actress who had once lived in that house. The third, and the longest one, belongs to a retired army officer, who too had inhabited the same house some time after the actress must have vacated it and is now speaking to someone who might be interested in claiming the debris. The last section belongs to a labourer connected with the demolishing of the house.

You can call this poem as Punjabi’s Sound and Fury (William Faulkner) or you can call it The People’s History of Punjab/Pakistan. Divided into four parts, Faulkner’s last part primarily focuses on Dilsey, the black servant, just as Najm gives the last part to the one on the lowest social rung in his society, one on whose back our ‘glass palaces’ are built. All the prior three narratives, however, are punctured by the presences of servants.

For its sheer complexity of voices, presences and narratives, this is no ordinary poem. This is no gul-o-lala, ba’ad-e-saba or sham-e-gham type of poetry. The idiom it employs is rooted in the socio-politico-economic reality of our time. For example, this is how the poem opens:

At least in two cases, that of the businessman and the retired army officer, the register of speech escalates quite a bit, especially in the case of the latter, trapping in their high and low registers the varied contours of a country’s turbulent past and present, not to mention their moral degeneration.

All the four monologues are addressed to a female. That in itself is worthy of deeper contemplation. The first three parts also flirt with a confessional tone. There is bragging, revealing of inner fears and longings and regrets. The last one is closer to a witness who understands the crime.

Sheesh Mahal, a palace built with countless mirror pieces, is a metaphor for self-reflection and, by employing four different points of view, Najm helps us understand how that process can have different results. Any word we utter is a reflection of our thinking. A sentence we speak is a wall of mirrors we throw out for others to see how we see ourselves. The monologue is a Sheesh Mahal. And each person, be it the businessman, the actress, or the retired military officer, can only see his or her own reflection.

The businessman only sees an opportunity to make money. The actress sees a possibility to free herself of societal constraints and it scares the hell out of her; she falls back in line. The military officer sees his own power reflected many times over, pumping further his already inflated ego. It is the labourer who knows that a person’s real worth is not in the mirror but within. For him the Sheesh Mahal is a witness stand which records human actions. The shadow that has cast its spell on the Glass Palace is the one that each inhabitant brings along. The shadow is the sum of his or her deeds which gets reflected back to the person.

The Sheesh Mahal is our collective conscience. This poem should be a mandatory reading in our college syllabus. It is the kind of poem families around dinner table should read and discuss.