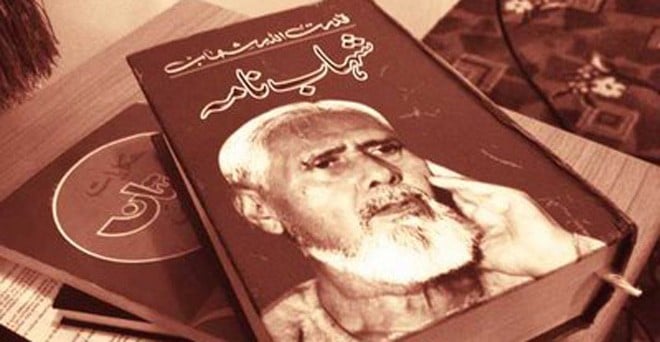

Rereading Shahab Nama, a tale of bureaucratic intrigues, camouflage, self-aggrandisement and subjective portrayal of events

Qudratullah Shahab (1920-1986) was a quintessential bureaucrat that Pakistan inherited from British India. He was one of the first Muslim officers to join ICS (Indian Civil Service) and served in Bihar, Orissa, and Punjab.

Under the Maharaja of Kashmir, Shahab’s father served in Gilgit where Shahab was born; he received his education in Kashmir and Lahore. At the age of 20, he joined the Civil Service and for the next 30 years served not only the British rulers but also spent substantial time very close to the early heads of states in Pakistan.

Usually, government officers do not put their experiences to writing but Shahab was an exception; he had a lucid style of writing with an ability to engage his readers. He penned numerous short stories too, but the most famous was his magnum opus, Shahab Nama, an autobiography that gives us glimpses into the British period as well as the lives of Pakistani autocrats such as Ghulam Muhammad, Iskandar Mirza, General Ayub Khan and General Yahya Khan.

Shahab was a well-read man who kept an eye on his own qualities and quirks. Being a favourite of the autocrats, he sometimes had to face allegations of equipping his masters with tricks of the trade; for example, it was rumoured that Shahab imparted the art of public speaking to Ayub Khan who - after taking over the reins of power - was finding it difficult to handle questions at public forums. Shahab quotes his friend Syed Zamir Jafry as saying:

Loosely translated as: The Q&A sessions are well-handled by the president and it is all the the fruit of Qudratullah Shahab’s training.

Shahab was well aware of what people said about him. In Shahab Nama he writes:

"When the Writers’ Guild was set up, some people thought it was my trump card to bring all writers and intellectuals to President Ayub’s fold; the government circles were rife with rumours that by taking undue advantage of President Ayub’s confidence the Guild was being used to shelter communists; when Pakistan Times, Imroze, and Lail-o-Nahar were forcibly taken over by the Ayub regime, this was also dubbed as my brainchild and in 1963 when the notorious Press and Publication Ordinance was promulgated that was also attributed to me".

In fact, so close was Shahab to the autocrats of his time that whenever Ghulam Mohammad, Iskandar Mirza, or Ayub Khan made changes in the government, Shahab would be found hovering around. Hafeez Jalandhari even wrote a couplet i.e.

(Whenever there is a revolution, Shahab is nearby)

This phenomenal success was not possible without a whole-hearted devotion to his work. He describes the qualities of a good bureaucrat in these words:

"If a decision is taken that is against the wishes of a bureaucrat, he has two options: one, he should accept the decision and honestly facilitate the implementation of that decision whether he likes it or not; two, he should muster enough courage to tender his resignation."

In Shahab Nama, he has not only touched upon his official feats but -- like a masterful raconteur -- also narrated some interesting events of his school and college days; for example, his recollection of an Urdu lesson by a Punjabi teacher is simply hilarious where the teacher struggles to explain to his students a couplet from Ghalib.

Since Shahab’s family belonged to Kashmir, his attachment to that region was deep-rooted and he had a textbook-like uniformity of thought with regard to all Hindus. He does not miss any opportunity to malign Hindus as a whole. Wittingly or unwittingly, he supported the official version of Pakistani history that is based on intolerance. This prejudiced narrative is a blot that Shahab Nama carries. He repeatedly calls all Hindus as ‘Hindu banyas’ -- one cannot miss a derogatory tone for Hindu merchants here. If by banyas, he meant usurers, one can find as many of them amongst Muslims as well.

Arguably, the very same Hindu traders and merchants played an instrumental role in the social development of their people resulting in the emergence of a strong industrial class while Muslims feudal Nawabs and Nawabzadas took pride in making fun of Hindu traders and merchants, so much so that till the 21st century we are still deprived of a strong middle class ethos that was engendered by Hindu traders and industrialist.

Shahab considered all the Hindus and British of the same ilk; just look at this sentence on page 154:

"The Englishmen and Hindus had one common streak, and that was considering Muslims as their enemy; and this collusion flourished".

Similarly he writes: "Banyagiri was an individual profession but in Calcutta a few Banyas had even opened a company that was named ‘Chaar Yar’ and this company used to get huge contracts from the East India Company."

This condescending attitude kept the Muslims backward and away from modern developments in trade and industrialisation while the so-called Banyas led their people forward. Shahab admits of this backwardness in Muslims when he writes:

"In 1880-81, in the English High schools of the subcontinent there were 36,686 Hindus and only 363 Muslim students. In the same year, India had 3,155 Hindus and only 75 Muslim graduates, that’s why in the administrative and economic set up of the country Hindus had a much better ratio".

Writing about Hindu-Muslim riots, Shahab presents a one-sided picture and does not even mention the killing of Hindus and Sikhs at the hands of Muslims. On page 176, he writes: "Bhagalpur RSS president, Kumar Indra Dev Narain Singh extorted money from the rich and his secretary, Satya Narain Pandey used to unleash his goons on Muslims who were killed and abducted; even Hindu peasants forgot their agitation and heartily engaged themselves in the plunder of Muslims."

There is no denying the fact that Hindus and Sikhs in some of their majority areas looted Muslims and killed and maimed; but, Muslims too, wherever they could, did the same; one should be reminded that not all Hindus and Muslims were involved in this barbarity; this difference needs to be kept in mind for the sake of impartiality that is expected of a good writer.

Shahab behaves as an official spokesman for Pakistan and tries to camouflage the struggle waged by the Indian National Congress in the freedom movement and has no word of praise for the Quit India Movement launched by the INC in 1942. He writes:

"On August 8, All India Congress Working Committee met in Bombay and adopted Quit India Resolution; Gandhi, Nehru, and Azad delivered fiery speeches. On August 9, the INC was declared a banned organisation and its all prominent leaders were arrested; hundreds of their workers went underground and loot, plunder, killings, and terrorism prevailed everywhere."

In this entire narrative, Shahab does not describe how the Muslim League came closer to the British rulers. All this has been beautifully narrated in Khan Abdul Wali Khan’s book Facts are Facts. Wali Khan’s book ranks much higher in terms of its research and analysis and students of history can learn a lot from this ‘unofficial’ history behind the creation of Pakistan.

Memoirs or autobiographies of bureaucrats should be read with a pinch of salt; reading them is like glancing through a tinted rear window. Self-aggrandisement and subjective portrayal of events and opinions are rampant in such reproduction of events: caveat emptor.