The fabric of today’s Pakistan was knitted in its formative years and the prevailing chaos is an outcome of decades-long patronisation of religiosity

The current crisis of Pakistan is a blowback having roots in its formative years. Departure from cardinal promises put the country on a wrong course and the angle of divergence widened with every passing day.

Amid obfuscated notions about Pakistan’s origin, one has to delve into history to unearth the reality.

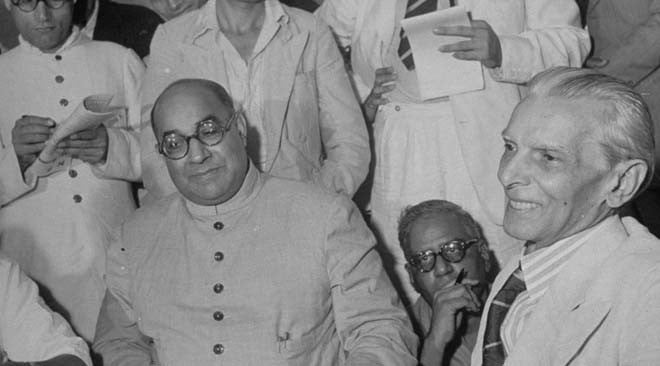

Textbook historians portray Mohammad Ali Jinnah as protagonist of an Islamic state. Browsing through the welter of work capturing his political and personal life one would broadly find him a non-conservative person yet an adroit politician who astutely blends religious citations to rally public support to reach his "moth-eaten and truncated" destination. Several of his speeches provide copious evidences that he never intended to create a theocratic state.

Orthodox religious outfits like Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam and Jamiat-e-Ulema Hind labeled him as Kafir-e-Azam, Muslim League as Kafir League and Pakistan as Kafiristan.

Jinnah viewed Indian dilemma through the prism of political and economic justice. It was the perceived political and economic insecurity of Indian Muslims and not any imminent threat to Islam that fuelled his struggle. Had he been of an orthodox Islamic state, he would have joined or at least supported the Khilafat movement. On the contrary both Jinnah and Dr Iqbal opposed the Khilafat movement and thus antagonized religious elements.

Jinnah castigated the Sultan of Turkey for exploiting Pan-Islamic sentiment to buttress his faltering empire. Long before his much cited presidential address to the inaugural session of the Constituent Assembly on 11 August 1947, Jinnah had been lucidly expressing similar thoughts at several occasions.

Addressing students of the Ismaili College in Bombay on 1 February 1943, he said "which government, claiming to be a civilised government can demolish a mosque, or which government is going to interfere with religion which is strictly a matter between God and man?" In a broadcast to the United States in February 1948, he said "In any case Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic state -- to be ruled by priests with a divine mission."

Jinnah demonstrated his commitment of respecting religious/sectarian plurality by appointing Jogendra Nath Mandal as the first law minister and Agha Zafarullah Khan, an Ahmadi, as the first foreign minister of Pakistan.

However, laying foundation of the new state on religion had already shaped an irreversible course. What unfolded in the subsequent years was travesty of Jinnah’s promises with millions of people who embraced the juvenile State in search of a future of their own choice.

By the time country came into being influence of religious lobby snowballed so overwhelming that Jinnah himself had to invoke Islamic references to justify his tenacity on the issue of national language.

Addressing convocation at the University of Dhaka on March 24, he firmly insisted "Urdu and Urdu only will be the state language of Pakistan. A language that has been nurtured by a hundred million Muslims of this sub-continent, a language understood throughout the length and breadth of Pakistan and above all, a language, embodies the best that is in Islamic culture and Muslim tradition."

While Jinnah ostensibly strove for a state to safeguard political and economic rights of Muslim minority, an orthodox lobby converted the country into a theocratic state against his own wishes.

Soon after independence, custodianship of ideological contours was taken over by people like Maulana Shabir Usmani and Maulana Maududi. Clerks belonging to migrant community were especially avid of invoking Islam in every sphere of state affairs. They astutely used the religion card for their share in the power-architecture and their political expediency in the years to follow. Their politics thrived by dint of religion.

Within no time after Jinnah’s departure, subterfuge of religious lobby fully dominated the course of new state. It led to a series of events that gradually plunged the country into an unrelenting orthodoxy.

Also read: Pakistan’s first decade

Objective Resolution in 1949, anti-Hindu riots in East Bengal in 1950 and anti-Ahmadi riots in Punjab in 1953 interred the putative secular vision of Jinnah within few years. The first constitution of Pakistan in 1956 formally named the country as "Islamic Republic of Pakistan" and the Objective Resolution was made the preamble of the constitution. This Constitution was abrogated when Martial Law was imposed in 1958.

When Gen Ayub Khan, the Chief Martial Law Administrator, enforced his Constitution, the word ‘‘Islamic’’ was omitted and it was named as ‘‘Republic of Pakistan.’’ However, during the first session of the National Assembly at Dacca, a member of Jamaat-e-Islami of the then East Pakistan, Barrister Akhtaruddin raised the issue and the word ‘‘Islamic’’ was added before the word ‘‘Republic of Pakistan’’ through the first Constitution Amendment Act, 1963.

Z.A. Bhutto enriched the Islamisation agenda by certain key insertions in the constitution. Article 2 of the new Constitution of Pakistan, for the first time, formally declared that ‘Islam shall be the state religion of Pakistan’. Similarly, in the oath of a public office a sentence was inserted "That I will strive to preserve the Islamic Ideology which is the basis for the creation of Pakistan". The Bhutto government declared Ahmadis as non-Muslims.

An otherwise non-conservative Bhutto attempted his best to placate religious lobbies, yet a conglomerate of religious parties finally walked him to gallows.

Gen. Zia’s era was the climax when raving religiosity permeated in every void of the public affairs. Whole complexion of the state was drastically Islamised. He established Federal Shariat Court and introduced draconian laws in the garb of enforcement of Sharia. Afghan Jihad cast the dye and the religion became a singular defining factor to formulate the foreign policy.

Whereas religion was blended in every sphere since inception, it was for the first time that Jihad became synonymous to national foreign policy and jihadis became new guardians of a nebulous ideology of Pakistan.

All this has culminated in making Pakistan a hotbed of religious and sectarian extremism that has sullied the image of country in the international community. The prevailing chaos in the country is an outcome of decades-long patronisation of religiosity. As a corollary, terrorism and extremism have emerged as the most sinister challenges to the future of the country.

Related article: Then and now

The second major departure from the promised state was depriving federating units of the political autonomy conjured before the partition. Both Jinnah and Allama Iqbal championed autonomous regions of Muslim majority areas within Indian federation.

Lahore Resolution of 1940, which is believed to be the cornerstone of Pakistan, envisaged ‘independent states’ in which the constituent units should be autonomous and sovereign. During the session the working committee was authorised to frame a scheme of constitution in accordance with the basic principles of the Resolution, providing for the assumption finally by the respective regions of all powers such as defense, external affairs, communications, customs, and such other matters as may be necessary.

These words make it abundantly clear that the Muslim League and Jinnah promised complete independence, sovereignty and autonomy for the proposed "states". Tragically, the sweet dream turned into a nightmare in the subsequent years.

The 1940 Resolution was the historic pledge of Muslim League that bewitched Muslim majority provinces of Sindh, Bengal and Punjab to accede to Pakistan. These were the provinces where Muslim League faced ignominious defeat only ten years before in 1936 elections. Sindh was the forerunner that adopted a resolution in favour of Pakistan on 3rd March 1943 and a special session of Sindh Assembly decided to join the new Pakistan Constituent Assembly on 26th June, 1947. Thus, Sindh became the first province to opt for Pakistan.

Needless to mention, Lahore Resolution was the main enticement. What transpired within a year after independence was in complete contrast to the Resolution of 1940. Volte-face and sassy attitude of Muslim League surfaced soon after the creation of Pakistan.

Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan who always purported to uphold democratic values and ethos of federation, was encircled by an opportunist coterie that always pursued its narrow interests in an infant state. Paradoxically his year-long brief stint as the founder Governor General was replete with several departures from the democratic norms that he emphatically propounded before partition.

What chagrined people of Sindh, NWFP, Kalat and Bengal was the autocratic and undemocratic attitude of Muslim League leadership that reneged on the promise of Lahore Resolution.

Enforced accession of Kalat under coercion sowed the seeds of relentless discontent among the Baloch. Arbitrary dismissal of Ayub Khuhro’s government when he enjoyed majority support in the Sindh Assembly and decapitating Sindh by separation of Karachi against the wishes of Sindh Assembly, Sindh Muslim League and people of Sindh alienated Sindhis.

Imposing Urdu as national language and repudiating a justified demand of a shared status for Bengali language enraged Bengalis. Unceremonious removal of Dr Khan Sahib and installing Abdul Qayyum Khan of Muslim League in NWFP was below the grace of democratic norms. These precedents set the convoluted roadmap for brutal martial laws, fratricides and frequent putsch of elected regimes. The fabric of today’s Pakistan was actually knitted in its formative years.