Culturally, we are brought up to show humility, but culturally too, we are required to assume a kind of gravity when we become men of letters.

In the fifty-five years that I have been meeting poets and writers of our country, I haven’t come across anyone who didn’t have a high regard for his work. (Faiz Ahmed Faiz was a rare exception). Chiragh Hasan Hasrat, (he of a large girth and a booming voice) who sent up everyone and every institution, became grumpy if his literary or poetic judgment was questioned. Meera Ji, in his mendicant’s garb, may have been the most unworldly of our poets, but he took it ill if his own verse was satirised. Ahmed Shah Bokhari (Pitras), one of our formidable intellectuals, who lampooned everyone from Hasrat Mauhani to Hamish Macrae, became abrasive when he himself was criticised. The arrogance that lies hidden within us, because of our outward demeanour of modesty, knows no bounds.

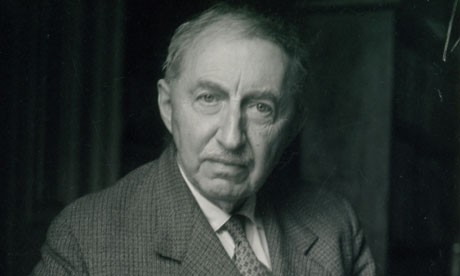

The essence of self-mockery lies in not considering yourself or your work to be prodigious and profound. When I asked E.M. Forster, one of the greatest novelists of the 20th century, which of his novels, he thought would be remembered the most, he smiled and said he did not think people liked remembering novels written by men who had regular haircuts. We both laughed. After a while he said, "I hope my books -- that is to say such sense and warmth there is in them -- will not be forgotten."

His modesty touched me deeply. He was the most self-effacing writer that I had ever come across. In the meetings I had with him, extended over a four year period between 1960 and 1963, I never once found him holding forth on any subject. He made me feel that everything I uttered was interesting and he listened to all my juvenile, rambling pronouncements with such attention that I felt hugely important. He was the most quintessentially civilised man that I had ever met.

In 1911, Forster first went to India to see his friend Ross Masood who had suggested to Forster that he should write an Indian novel. Forster told me, on more than one occasion, that but for Ross Masood, he might never gone to his country and written about it. He once wrote: "I didn’t go to India to govern it, or make money, or to improve people. I went there to see a friend."

Forster stayed in India for six months. He travelled a huge amount. A great deal of what he saw and heard would go straight in to his novel. In Lahore he was introduced to a Mr. Godbole who talked to him about Ragas and sang to him as they walked through the public gardens. In Hyderabad, Deccan, a friend of Masood lost his temper and had an outburst against the English saying "It may be 50 or 500 years, but we shall turn you out." Both these episodes are vividly recorded in the novel and its dramatisation.

Since the publication of his diaries there has been a renewed interest in Forster’s Indian novel. He began to write Passage to India in 1913 but finished it in 1924. According to the Forsterian scholar, David Galgut, "it is safe to assume that a specific element of the novel was causing him trouble. It was the question of what happened or didn’t happen to Miss Quested in the Marabar caves, that became the stumbling block. The episode is of course central to the novel."

Galgut tells us that in his first draft Miss Quested is subjected to a physical attack though it is not clear by whom exactly. She becomes aware that somebody has followed her into the dark and assumes that it was Dr Aziz. Forster had no clear idea in mind about his essential aspect and he, unhappily, abandoned the book.

Galgut says that the solution that Forster eventually decided on is perfect because it is ambivalent. Forster doesn’t show what happened in the caves. We see Miss Quested running away down the hill, getting tangled in thorns and all we have to go on is her feverish memory of being assaulted. "The attack," writes Galgut, "is imaginary, what a psychologist would think of as repressed fantasy: Miss Quested is in love with Aziz, but cannot say so, act on her feelings and instead turns them inside out, into violence against herself."

Having seen the first draft, Galgut found that the description was halting, unconvincing. He concludes that Forster, a shy and retiring man was never good at writing about violence, but in this instance, "the action is unpersuasive because its author is only half-involved. The writer can sense that he’s going in the wrong direction, but is trying to force a way through." He reminds us that in an interview, in 1952, Forster told a French journalist, "When I began A Passage to India I knew that something important happened in the Marabar Caves, and that it would have a central place in the novel, but I didn’t know what it would be."

It is no secret that Forster was deeply in love with Ross Masood whom he tutored in England. Foster had declared his feelings but Masood was straight and couldn’t reciprocate. When Masood finished his studies he returned to India. Forster followed him a few months later. Galgut, who has traced every step of his journey, tells us that he went to Bankipore where Masood was living at the time. Bankipore was close to the Barabar caves which became the Marabar caves in the novel. The night before he visited the caves he made some sort of overture to Masood but was rebuffed once again. Deeply hurt, he left for the caves the next morning. He didn’t see Masood again until his second visit to India in 1922 by which time Masood was married. The two men then remained life-long friends.

David Galgut asks a pertinent question: "Is it too fanciful?" he writes, "to imagine that everything Forster must have been experiencing -- a confusion of love, sadness, disappointment, and possibly anger -- was projected on to the caves and took form in the imagined attack? It’s never explicitly stated in the novel, but it is obvious that Miss Quested is attracted to Aziz. If the assault is a fantasy, it’s because her desires have no outlet -- and the same could be said about Forster." A moot point.

It matters not whether you read A Passage to India as a novel about the Raj, a political novel, or a as a novel which depicts repressed longings and fears, Forster’s ‘sense and pain’ comes across as sharply as the mid-day sun -- and, in my view, it will never be forgotten.