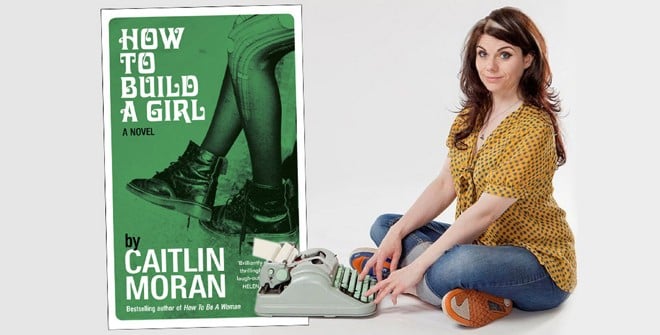

On Caitlin Moran’s How to Build a Girl, Mary Beard’s Laughter in Ancient Rome and other things

Two delightful similes form Caitlin Moran’s new novel, How to Build a Girl: "Lupin’s eyes are massive. They take up half the room" and "Mother’s eyes are so hard they make the tinsel on the Christmas tree shimmer."

Caitlin Moran -- column stand interviewer of The Times -- has, at the age of 36, achieved so much fame that she has got her photo in the National Portrait Gallery, an honour not bestowed on many journalists. Her twitter feed is going to be used as A’level set text. "Like a rock star," says the Sunday Times, "she is about to go on tour and every date has been sold out."

Ms Moran is a child prodigy who grew up on state benefits in a Council Estate in the unromantic town of Wolver hampton. She wrote her first novel at the age of 15 and became a journalist at 16. ‘How to Build…’ is a novel about a lonely girl, Johanna Morrigan, who lives in a Council House in Wolverhampton and, like Moran, starts writing for a pop magazine at the age of 16.Although Moran denies that the novel is about her life, it is hard to imagine that she hasn’t drawn on her own experience. I haven’t yet finished the novel but I can tell you that it sweeps you off, and it is very droll.

* * * * *

One of the television programmes I was fortunate enough to see was an intensely absorbing documentary about the four highly gifted Australians who migrated to England in the 1960s: Clive James, Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes and Barry Humphries. All of them made a big name for themselves in London, Germaine Greer as a novelist and social analyst, Clive James as a critic and author, Barry Humphries as a brash but achingly funny drag queen, Dame Edna, and Robert Hughes as a commentator on the world of art and music. They all achieved star status on television. Each of them brought an invigorating original flavour to their work. With their individual styles they not only changed the temperature of public discussion, comedy and social politics, but also created a huge dent in the reactionary cynicism of the establishment.

The four of them were all critics. The programme revealed that they were the acceptable face of criticism, not just acceptable but "the popular and funny face of criticism." The amazing fact is that all of them remained remarkably consistent for a little more than five decades. Few writers, commentators or comedians manage to sustain their freshness for more than half a century. The four Australians brought an intensely considered cerebral liberty that was foreign to British television. The documentary confirmed my opinion that intellectuals are architects of change and improvement, both social and aesthetic.

* * * * *

July was an exceptionally warm month in England. Day after day I heard people whose faces had turned pinko-red, say, "Oh it’s a scorcher." Poor souls, they had no idea what they were talking about. Only we, living in the pulverising humidity with a temperature never under 39 degrees centigrade, know what scorchers are.

The days were warm but if you sat under the shade of a tree it was blissfully pleasant. The book that I enjoyed reading most, sitting on a bench under the ancient oak tree in the communal garden facing the flat in which I stayed, was Mary Beard’s Laughter in Ancient Rome with the sub-title On Joking, Tickling and Cracking up.

Mary Beard is a Cambridge don. A few years ago she prepared a series of lectures on what exactly did the Romans find funny. She delivered these lectures at the University of California in Berkeley. The lectures have now been collected into Laughter in Ancient Rome and they are highly informative.

The sadistic Roman emperor, Caligula, of whom the historian, Cameo, has written that once, at some games at which he was presiding, he ordered the guards to "throw an entire section of the crowd into the arena during intermission to be eaten by animals because there were no criminals to be prosecuted and he was bored", had a similar taste in jokes. At one of his more lavish banquets, he suddenly collapsed into a fit of guffaws. The consuls who were reclining next to him asked politely why he was laughing. He replied, ‘only at the idea that at one nod from me both of you would have your throats cut instantly."

Ms Beard’s exhaustive research leads her to observe that "A Roman located the responsibility of any form of deformity, regardless of its origin, solely in the person who bore that deformity. In consequence the Romans laughed a lot at the bald, crippled, the dull-witted, old women, or deafness, the black-skinned and the blind". They loved to mock the inhabitants of the eastern Mediterranean cities because of their dark skin. One popular joke, she quotes, is "Did you hear about the messenger from the city of Abdera, who ended up being crucified? He is no longer running, he is flying."

She has also traced some jokes (very popular in London in the 1960s and 1970s) to the Philogelos, the largest surviving collection of Roman jokes, dating from about seventeen hundred years ago. Example: A garrulous barber asks his client how he would like his hair cut. "In silence," was the reply I remember hearing this from the austere Tory politician, Enoch Powell, on television.

A startling revelation Professor Beard has made is that the Romans did not smile. Romans meeting on street might have greeted one another with a kiss but they did not smile. "Smiling, an invention of the Middle ages, is polite; the Romans were not polite." She goes on to explain that smiling is "one of the most powerful signifying gestures in the modern western world signalling warmth, greeting, wry amusement, disdain affection, ambivalence and much more."

Presumably, she concedes, there must have been some intervening stage between solemnity and outright amusement, some upward curl of the edges of the lips that was a precursor to laughter but even if there was such a facial adjustment, it was not one to which the Romans attached much cultural importance.

* * * * *

Looking at a few of the TV series which purport to be penetrating studies of how the middle and upper middle-class people live in England today you find that Britain is as riddled with corruption as any other country. Why then is it that most people still refer to it as Great Britain? The country isn’t free of corruption and probably never has been. The fact, however, remains -- and Transparency International confirms it -- that Britain is noticeably more honest and free from corruption than most other countries.