The western practices of literacy contrasted with culturally different practices of literacy in world history

In today’s world, the ability to write and read is the primary condition of literacy, which is supported by international conventions and institutions like UNESCO. Our schools drill the children into the practices of writing and impart knowledge through reading of books.

Although books have been an integral part of education in every human civilisation, the relationship between the author and the reader, and the definition of literacy have varied across cultures. In some cultures like in historical India, books were not always written by scholars or read by readers. In many cases, the books were dictated by scholars to scribes, and heard by the students/scholars through orators/readers.

All that changed with the advent of colonialism and spread of printing press in the 19th century across the globe, after which the non-western knowledge systems underwent radical transformations. The historical experience of literacy of the west was turned into an educational model to be deployed universally in the name of "civilizing the natives".

Our current intellectual impasse and educational scenarios are a product of this colonial encounter, whose itinerary is yet to be charted.

In the following paragraphs, I will briefly profile the western practices of literacy and contrast them with culturally different practices of literacy in the world history in broad brush strokes.

Writing acquired its prominence in the educational discourses of the 19th century Europe, where it was argued that since the invention of alphabet script in seventh century B.C., the famous ‘Greek revolution’, the acquisition of literacy through reading and writing caused a qualitative change in the perception and cognition of individuals and societies. Writing was considered a mark of "civilisation", that is, to be civilised is to be able to write.

Anthropologists and missionaries ranked non-western societies as "primitive" or "illogical" due to the absence of writing skills and literate population. In the twentieth century, the literacy and writing was seen to have played a major role in the historical development of European societies, especially in providing a foundation for democracy, bureaucracy, and scientific method.

A history of writing material and practices from ancient to modern times reveals the extensive use of manuscripts and writing materials at various tiers of society in combination with orality. Instead of perceiving orality and literacy as binary opposition, with foundational differences in terms of ‘techniques of intellect’, we need to see intersections between the composition, transmission, reception and reproduction of a piece of knowledge in different modes of social reproduction.

A noteworthy contrast to dominant literate tradition based on print literacy in Europe, the Arab civilization, which spread to North Africa and South East and South Asia in the centuries following the advent of Islam in the sixth century, evolved a different interface of orality with writing. Manuscript publishing in multiple languages through Arabic script continued to explode for several centuries even before the invention or the aid of printing press through oral recitations of scholars committed to writing by a large number of scribes.

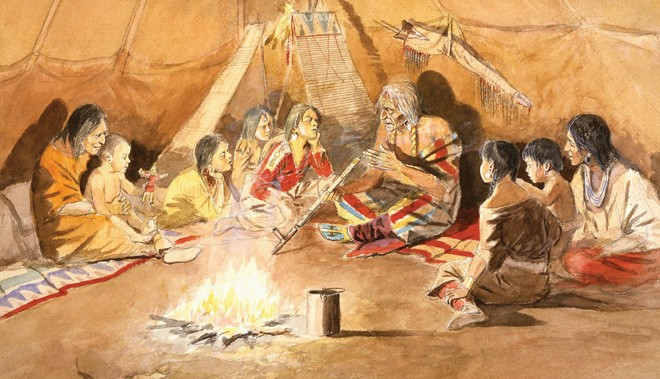

In the Indian tradition, a unique form of literacy, called by Indian scientist Prof R Narasimhan as ‘tacit literacy’, emerged and allowed individuals, who are part of an essentially oral milieu, to engage in complex literate performances. The forms of articulations that have normally been considered to be available only in the literate mode through the explicit use of writing have been developed and perfected in the Indian tradition using purely oral techniques. Such techniques were used not only to memorise and transmit across generations complex texts in syllable perfect form, but also to support teaching and preservation of structurally complex performing arts and other cultural practices.

Such techniques can explicitly illustrate not only in the context of "high" culture, but in folk performances, and in the learning and practice of craft skills.

Before the Norman conquest of England in 1066, right to land was held through such socially verifiable and integral means as the swearing of an oath of "twelve good men" along with possession of seals and symbols that represented the right to land entitlement. The colonial bureaucracy in the medieval England imposed a detailed record keeping of the land entitlements, which led to a shift to literate modes. The "English natives" were embedded in an alien system in order to maintain holdings that provided their livelihood, while the conquerors became dependent on rolls, records, and written laws in order to acquire and control the knowledge that gave political power and legitimacy.

Literacy was a terrain, over which the struggles between colonised and the conqueror took place in the medieval world, as it continues in many third world countries today.