The proximity of incidence and the Pavlovian theory

Up early morning on the 9th of August, I was all set, rather anxious to get back to Lahore from Abbottabad. I sat on the bus. I had been hearing news of things not being ‘safe’ and my parents worriedly telling me it wasn’t the best day to travel but I, like many of the people who have grown up with me, have heard this all too often.

What could possibly go wrong? The news is always bad, something is always happening, but that doesn’t stop life from going on.

A book in hand, not a care in the world except for reaching home or finishing the chapter I was reading, what came next was something I hadn’t anticipated.

We were on our way. Everything seemed set, other than us stopping after every fifteen minutes. Each time some passengers would get out of the bus and come back in with a story of why we had stopped: first, it was a landslide that was being cleared, then it was some VIP convoy that was passing, and each story had its own logic and evidence. I was impressed by how the people could think up when in need to explain an anomalous event.

It was at Bhera, the actual routine stop for the bus, that we were to realise what was happening. I had dragged my cousin who was travelling with me to Subway for a meal where the waiter refused to serve us saying that the restaurant had been closed. Confused, I saw a crowd of people staring at the road. Curious to know what they were looking at, I set myself up in between the crowd in a position where I could see the road. What I saw was something that you see in films or on news channels that tell us about distant places which might in all actuality be far closer than we presume them to be, the distance coming from the seemingly lack of impact that these events have on our life.

The Police and Tahir Ul Qadri’s political workers were in a confrontation, both with sticks in their hands ready to harm the other at will, the police firing shell gas in an attempt to stop the rally while the protestors vehemently pressing onwards.

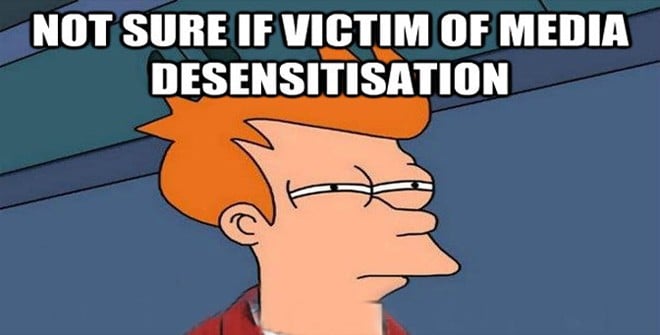

I knew how one should react -- with awe and fright -- but for some reason what was going on in front of me was neither awe-inspiring nor frightening; it was the kind of stuff movies are made of. I had realised the gravity of the situation and all the dangerous things that could possibly happen but I still felt strangely calm enough.

Even though the physical proximity had decreased, the ‘distant’ had not gone. I had become ‘desensitised’ -- or, perhaps, ‘inoculated’.

Inoculation is the process where after being injected with a small pathogen the individual becomes immune to the larger disease. Watching these things on news channels had made me think this was routine. The safe distance that the TV screen afforded me had given me a sense of being safe and so, like Pavlov’s dog, when I was seeing the same thing in reality I had been conditioned to feel secure.

What makes me look into myself is the fact that those people who had actually come out into the street had not been inoculated. They could feel so much more than I could; they were the players and I was still the spectator. What was it that made them so radically different from me and the other passengers in my bus? Their motive may have been contentious but the fact that they were in the street meant that they had felt something worth putting their lives on the line for.

This incident left me wanting to ‘feel’ and find a cause worth fighting for where I am not a spectator but an actor.