To what extent did Zulfikar Ali Bhutto open up the doors for the ‘Islamic’ laws later brought in by Zia?

The image of General Ziaul Haq will live with us for a very long time: a nightmarish memory for those who can remember flicking on their television screens to face the wide-toothed grin, the eyes ringed by deep shadows and the distinct moustache of a man who would rule the country for 11 long years, changing its contours forever.

By 1988, when Zia dramatically vanished from the scene in that mysterious C-130 air crash over Bahawalpur, Pakistan had changed beyond recognition, cast in heavy chains under a set of ‘Islamic’ rules with hardline sects ushered in to open their madrassahs in a nation where religious ritual overtook all else.

The legacy lives on with us today, firmly entrenched in the very air we breathe. It is impossible to escape it, with the clauses inked into the Constitution, pinning down Zia’s vision even more firmly.

As extremism has grown, the problem has worsened, with the growing misuse of the blasphemy laws offering just one example of this. It is a frightening one. We see the consequences again and again.

Perhaps because we like to think in black and white -- casting people in roles of heroes and villains rather than those who stand between the two; perhaps because of Bhutto’s tragic end at the gallows, we tend to place the entire blame for what has happened to our country entirely on the shoulders of Zia.

This is the easiest way to deal with the past for many of us; the simplistic way, and generally we like to steer clear of too much complexity and too much deep thought.

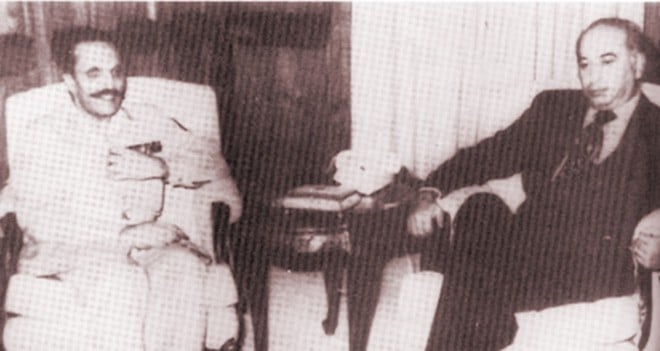

But to what extent did Zulfikar Ali Bhutto open up the doors for the ‘Islamic’ laws later brought in by Zia? What part did the Pakistan People’s Party government play in weaving religion tightly into the affairs of the State, and in the process, breaking away from the Left-leaning agenda that had brought it to power following the 1970 elections when people voted for radical change?

After that election, the Left has, of course, never figured as a force in Pakistan’s electoral politics, and Bhutto himself played a key role in this, ‘cleansing’ his party of its leftist members as he, starting in 1974, linked up with the establishment -- essentially to keep checks on his rivals, both within and outside the party.

This unsavoury alliance led to acute differences developing between Bhutto and key founding members of the party, including Malik Meraj Khalid, Dr. Mubashir Hassan, and most notoriously the Bengali communist leader, Jalaluddin Abdur Rahim, who chose to stay with the PPP in what remained of Pakistan after the 1971 civil war.

Rahim, who had served as law minister in the PPP cabinet, criticised Bhutto in public, was imprisoned and tortured. This episode was among those which marked the demise of the PPP as it had been when it first came to power.

There were other measures which laid down the first bricks on the road that Zia would follow. Bhutto perhaps could never have imagined the kind of country Pakistan would become. Today, he would not recognise it. But the policies he adopted played a critical role in bringing about the change.

The direction we looked in began to alter, with heads turning to the West and the Middle East, as the process of plucking Pakistan out of South Asia and placing it closer to the Arab world began. This was partially an outcome of the 1971 war, but the effects would be long-lasting.

As Pakistani workers left for Gulf States their remittances altered economic emphasis and new bonds began to be formed with Pakistan, stepping forward to assist its allies with technical and practical support during the 1973 Arab-Israel war.

The highly successful Organisation of Islamic Conference held in Lahore in 1974 marked this new era. The slide westwards would be taken far further by Zia, who, to a much greater extent than Bhutto borrowed cultural and religious influences from that part of the world, attempting to eradicate a past created through the centuries.

At home, under growing pressure from the Pakistan National Alliance, a broad-based alliance set up against his government, Bhutto began to divert from the originally secular stance of the PPP and use Islam as a prop; a tool to gain popular support.

The PPP’s failure to go through with many of the promises made in 1970 and based on its 1967 manifesto quite evidently drove forward this strategy by a leader desperate to avoid any loss of control.

Dangerously, under pressure from the religious right, discriminatory laws were built into the Constitution. Ahmadis were declared non-Muslim in 1974, opening the way for the growing violence they would face through the Zia era and later. Shariah laws, banning alcohol sale to Muslims, appeared a few years later. Tinkling wine glasses vanished from tables, and with them went free choice and the dream of a liberal Pakistan that some still held on to.

Bhutto himself, a man who never claimed to be a practising Muslim, resorted to the use of more and more Islamic jargon, organising a Seerat Conference ahead of the 1977 polls and altering key components of PPP policy to gain popular support. Requirements, such as the one that the head of State be a Muslim, crept into the Constitution. They have, of course, remained there.

Of course, attempts to ‘Islamise’ Pakistan had begun decades earlier. They assumed their harshest form under Zia. Had Bhutto survived as a ruler, we would almost certainly not have seen the kind of horrors that marked Zia’s years in power: the floggings, the public hangings, the brutal stripping away of rights from women and minority groups and the alterations in law that have re-shaped society.

Today, politics and religion ride together, pressed close to each other. This is, undoubtedly, what Zia left us with. Religion and promotion of extremism were the hallmarks of his rule. They helped prop him up as a leader who exercised immense coercive power. But the path towards bringing Islam into the lives of people who already practised it was begun by Bhutto, as he led his party in a different direction to the one envisaged by its founders.

We can only guess what the outcome may have been had he not caved in to pressures which could have been avoided by keeping with the original line of the party. But all this now is, of course, a part of history. Today, we see where the direction taken has brought us, and we can only wonder if we would be standing at a quite different place had policies between 1971 and 1977 been different.

It seems almost certain that this would, indeed, have been the case, possibly even staving off the arrival at the helm of State of General Ziaul Haq, the man who would change the face of our country forever in so many different ways.