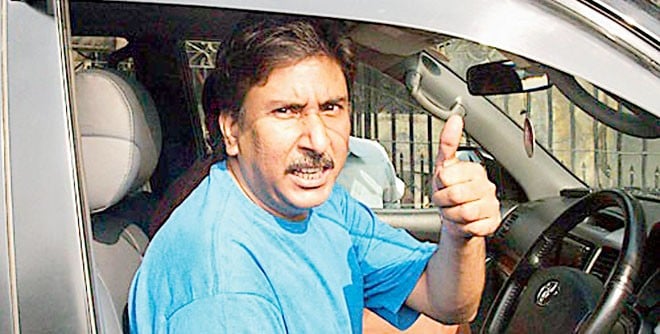

A flawed genius, Salim Malik remained a mystery. He mostly lived the life of a recluse, even when he was captain. He was a maestro whom the world never fully recognised

When I heard the news that Salim Malik’s pension funds would be unfrozen and given to him, it unfroze inside my mind the memories of a brilliant batsman and cunning cricketer. The news came with mixed emotions; but not equally. For a strange reason I always carried a tear for Malik, the proverbial flawed genius. His is a story of a truly gifted man who sought more, perhaps too much. It was like an artist destroying himself, though it must be said that he braved most of it; albeit with a big piece missing from his armoury, and that was the supreme self confidence he displayed while batting, capable of repulsing or taking apart any attack, anywhere when on song.

He remained a mystery though, frozen in his own world. He mostly lived the life of a recluse, even when he was captain. He was a genius whom the world never fully recognized. I asked Inzamam after he’d retired as to who was the best captain he had played under. His answer in his typical soft spoken accent was that after Imran Khan, it was "Saleem bhai".

His career is a Shakespearean tragedy, perhaps Macbeth best embodies him. Malik came from a less privileged family, didn’t go to college and more so because by the time he was 19 he was playing for Pakistan’s Test side. Till a year earlier he had been playing for Pakistan Under-19s and in the same year, while playing a representative match had also stood up to the then fastest bowler, Michael Holding, at his peak.

He reached a hundred in his very first Test -- against Sri Lanka who were in fact playing their second match after getting Test status a few weeks earlier. But though nothing could have stopped him from playing at the top level, his inclusion at 19 had come primarily because Majid Khan and Zaheer Abbas among 10 senior cricketers were sitting out the series in protest against Miandad being retained as captain, after what they believed was a campaign by him to discredit them after returning from the tour of Australia.

Malik showed both muscle and class in the 1984 home series against England, in which it can be said that ‘he arrived’. I was fortunate to be on the grounds when he pummeled the touring English bowlers to submission. Often he would hit cover drives on the up, and you could see that from the wiry lad he had developed into a full-chested man; Majid Khan in fact pointed to a slight paunch and felt he wasn’t exercising enough.

Malik couldn’t really get along with either Javed Miandad or Imran Khan but that wasn’t so much his fault. Malik knew his talent was in many ways as good as Miandad’s and he had his own mind. Miandad wanted total recognition within the team and Malik was not suitably impressed. With Imran it was a huge personality gap, the elite Oxfordian against the ordinary Lahori, though both started playing their cricket in Lahore. Imran felt more comfortable with either contemporaries like Wasim Bari, Sarfraz Nawaz, Mudassar Nazar or with boys he could call his own product, like Abdul Qadir, Rameez Raja (Malik’s Under-19 captain), Zakir Khan, Wasim Akram and their like.

Two instances show how both Imran and Miandad put either less confidence in Malik or allowed their personal preferences to overrule his stature. In an ODI in Calcutta on the 1986-87 tour, Imran held him back as Pakistan chased the tough target set by the Indians. Malik sat padded up immensely frustrated and angry that Imran sent Manzoor Elahi and Abdul Qadir ahead of him and then went in himself. When he eventually strode in at No.7 some 80 runs were needed off ten overs. Imran departed almost immediately afterward and Indians were celebrating a perceived victory. It was then that Malik unleashed himself upon the best India could throw at him, scoring a blistering 72 off 36 balls to single handedly turn the tables. Though tactically justified, (Inzi had won the semi-final and Akram was sent in for his pinch hitting powers and a right-left partnership) Salim Malik walking in to face the last ball of Pakistan’s innings in the 1992 World Cup final was one of the most heart breaking sights I have seen in cricket.

Also, in a domestic one-day final somewhere in late ‘80s, Miandad was captaining HBL and sent in his brother, an average batsman, ahead of Malik who could be seen pacing up and down in the pavilion at the insult. The run rate staggered and it was not until Malik arrived at the crease that the bowling was taken to task. Upon reaching a swift fifty he turned to the pavilion and raised his fist.

Both needed him of course. If not for Malik, Miandad would have struggled to even draw on difficult pitches and it was Malik with his 99 on a seaming pitch who helped Imran beat England at Headingly in a five-Test series which Pakistan won 1-0, the first time Pakistan had won a series on English soil.

Malik truly came into his own when both retired and after becoming the compromise captain when the whole Test side rebelled against the captaincy of Wasim Akram in 1994, he produced his best cricket, both as a batsman whether he was tackling Shane Warne with utmost ease or tactically maneuvering his team to victory or a fighting draw.

He always led from the front, with a double hundred and hundred against the powerful Australians that saved Pakistan from defeat.

But it was the period when the power of being a captain fully brought out the dark ambition in him. He was accused of match-fixing, the first time any cricketer had been publically named. Rashid Latif led the chorus after Malik opted to field in a day-night ODI when it had been agreed unanimously that Pakistan would bat first if they won the toss as chasing against lights against a South African attack on their own pitches was not on. Couple with the accusations of Shane Warne and Mark Waugh, Malik was suddenly thrust as the man who was corrupting cricket.

Malik lost his captaincy as he vehemently denied the charges but was never the same man again, either with the bat or tactically. He did not help his cause after the 1999 World Cup when he carelessly succumbed to a sting operation by a British tabloid in his London hotel room, revealing that he could fix a match allegedly for an eight figure sum. Coming on the back of Pakistan’s inexplicable loss to Bangladesh in that tournament, where Malik was in the playing eleven, it created a furor. Malik claimed after publication that he knew he was talking to journalists and not bookies and that he had led them on just out of fun. But the damage had been done and based on that and recorded accusation by team-mates, he was banned from all cricket by Justice Qayyum in 2000. After some 18 years, close to 6000 Test runs with 15 hundreds at an average touching 44 and over 7000 ODI runs with 5 hundreds and 47 half centuries despite usually batting in the middle order, he left cricket with his image tarnished, his achievements unremembered and literally wiped out from people’s memories.

Malik fought back stressing that, alongwith Ata-ur-Rehman (who was an ordinary bowler and was no more in the Pakistan side) he had been made a scapegoat to save bigger names at the time. He had a point considering that there had been damaging evidence placed against Wasim Akram, and insinuations against Mushtaq Ahmed and Waqar Younis, who were simply fined.

Was he or wasn’t he involved? If yes, was his crime greater than the others who till today enjoy legendary status? Indeed when you unfreeze his cricketing contribution to Pakistan Salim Malik stands alongside the best batsmen our country has produced and can be counted among the best thinking, strategizing captains to have led an international side.