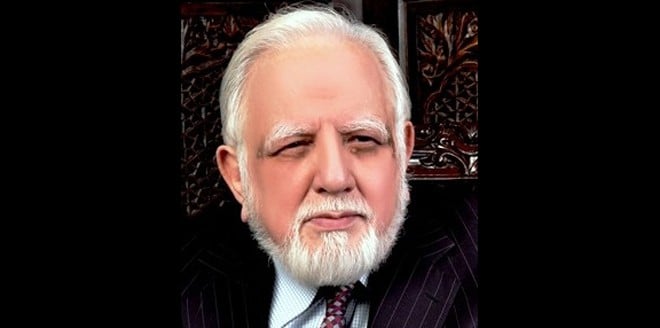

Sheikh Mujeeb ur Rehman, senior advocate of the Supreme Court, looks into the social aspect of Ahmadis' seclusion in the state and society

The News on Sunday: How do you see the connection of the 1953 riots against Ahmadis and the 1974 decision by Bhutto’s parliament that declared Ahmadis non-Muslim?

Sheikh Mujeeb ur Rehman: I would like to explain this through going back a little in history. When the struggle for Pakistan was going on by the Muslims of the then India, there was a clear divide amongst the Muslim society. The bulk of mainstream Muslim clergy opposed the Pakistan Movement on strong religious grounds. The Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind had its own reasoning and so did the Jamaat-e-Islami. Jamaat-e-Islami’s view was that a nation-state is anathema to Islam; Islam knows no frontiers. Therefore, Maududi was opposed to the idea of the nation state. Jamiat-Ulema, also known as the nationalist Ulema, thought the Indian subcontinent need not be divided and they can work for Islam in the combined Indian state.

In 1930s, Iqbal said the non-Muslims need not be afraid as Pakistan would not be an Islamic state, and Maulana Maududi was very clear that Pakistan would not be a theocratic or an Islamic state. But when they came to Pakistan they started scrambling for an Islamic state, Islamic constitution, and law. And then they gained an inch of ground in 1949 with the passing of the Objectives Resolution. Then came the 1953 agitation, which was put to inquiry before the commission. The commission asked pointed questions to the JUI and JI about the definition of Islam -- and they categorically stated that Quaid-e-Azam’s concept of Pakistan as enunciated in the August 11 speech was a satanic state -- shaitaan ki takhleeq. They said that the demands of 1953 agitation Islamic state was an attempt at steering Pakistan towards that Islamic state.

The religious issue was exploited for political purposes. The provincial government of Punjab wanted to divert the agitation towards Karachi, and fanned the agitation because Mumtaz Daultana wanted to be the Prime Minister of Pakistan. In that political context, religion was used as an excuse. The Munir Inquiry Commission Report found out that Muslim clergy could not decide on what would an Islamic state look like, what is the status of non-Muslims? That demand for declaring Ahmadis as non-Muslims was rejected by the Commission. Twenty years later, Bhutto picked up that issue.

The difference is that the 1953 agitation was created by the local clergy and politicians for an agenda, which was based on domestic politics.

In 1974, when it was all quiet in Pakistan, PPP students staged a riot at the Rabwah railway station, which was made the basis for taking the issue to the National Assembly. This was clearly planned and Mr Bhutto made use of that situation. He did that under the pressure of international players. When he did that, Ahmadis clearly stated that the National Assembly did not have the jurisdiction to take up that issue. They took the stand that the constitution and religion are two entirely different jurisdictions and that the constitution and state had nothing to do with the religion of an individual citizen.

The Pakistan National Assembly was guilty of usurpation of constituent authority. I am using these technical terms for a purpose. But they assumed that jurisdiction. Even so in 1953, the Munir Inquiry held that the Ulema did not agree on a definition of a Muslim and failed, and again in 1974 the Assembly failed, too. The Ahmadis kept asking for a definition of a Muslim but they only agreed on a definition of a non-Muslim. So, the second constitutional amendment was passed, which according to me, in the political world is a non-existing thing. It is legal fiction.

In fact, all troubles of Pakistan arise out of the 1974 amendment, as it polarised the society.

TNS: How did the 1974 decision lead to the Ordinance XX 1984 which specifically discriminates against Ahmadis?

SMR: When Ahmadis were declared non-Muslims, the Ahmadis put up with that. They swallowed the bitter pill but the clergy did not let go. All of a sudden there was a spate of litigation by the Ulema, especially in Punjab. In 36 districts of Punjab, there were civil suits pending that the Ahmadis should not pray, they should not invoke durood, their mosques should not have domes, the attitude was that they were declared non-Muslims now we will turn them into non-Muslims.

Civil suits take long time. They asked for stay orders to stop Ahmadis from praying in mosques. But one mosque in Dera Ghazi Khan was sealed as the local court gave them the stay. So, the case was then brought to the Lahore High Court and LHC gathered all cases from the 36 disctricts, and a Double Bench heard the case. In Abdul Rehman Mubashir vs Syed Amin Hussain Bukhair, PLD 1978 Lahore, the court gave the verdict that Ahmadis, despite being declared non- Muslims, had been saying the same prayer for a 100 years, they follow the Holy Quran and Hadith, yes there are a few differences. They court said that "Ahmadis are non-Muslims of a special kind". These are the court’s words and these practices are as much their practices. The court then observed that they can build mosques, give call to prayers, and say their prayers, after a 14 day long debate from constitutional and religious angles.

The clerics then could not do anything. That became the law. Then the clerics became loud only when Zia-ul-Haq appeared on the scene. Zia was gasping for legitimacy. Then Ordinance XX, Un-Islamic Activities of Ahmadis Prohibition Ordinance, was issued through a martial law ordinance and said in the beginning of it that this ordinance shall have effect not withstanding any judgment of the court. They wanted to nullify the court’s verdict. Now the Ordinance XX has protection through eight Amendment. Therefore, parliament is protecting a law made by martial law in Pakistan.

TNS: What do you think about the Ordinance XX 1984?

SMR: This ordinance is ridiculous, illogical, unconstitutional and un-Islamic. Everything it prohibits Ahmadis to do is technically Islamic. The application is absurd. Why are people accepting an ordinance which stops you from saying salam? It can go if the civil society and human rights groups make an effort.

TNS: Have the courts given in to the pressure of the clergy after 1984 Ordinance XX?

SMR: There is no blank answer to this. Yes, the courts did cave in in many cases. Our Supreme Court came under pressure. In Zaheeruddin vs State case of 1993, during which I was arguing the criminal appeal, there were posters in Rawalpindi propagating that the court is pro-Ahmadis, which the police had to take off. There were many indications in the verdict of the pressure on the court. It is my observation from representing many cases. Now the courts are not just under pressure in Ahmadi cases but many others due to the threats from religious extremist organisations. Please look at the verdict on Mumtaz Qadri.

TNS: Can the courts fight back and how?

SMR: Yes, there has been the will to do justice in the court as they are trained. But they are not that independent yet. The courts cannot change the system without the help of the civil society. As it is not just the religious minorities, but the majority of the country, including the government, are held hostage by forces of religious extremism. Majority is under threat.

The question is not that of the Ahmadis, it is that of the entire Pakistani society. Forty years have passed since the passing of the Second Amendment. The whole idea of Pakistan is under threat. Nobody wants the Islamic state of Mullah Omar in Pakistan, I know that.

Pakistan society is not fundamentalist and that is why I am hopeful. I believe that the conscience of the society is not dead yet. It is just that anything that destroys social unity is worthless, and that needs to be recognised in Pakistan.

Rehman’s book on the Pakistan National Assembly’s decision to declare Ahmadis non-Muslims in 1974 is due in September. Rehman is an Ahmadi and has represented his community in many high profile cases since 1974 in the Pakistani courts.