Oscar Wilde blames only himself for letting himself be degraded and for succumbing to the excesses that led to his tragedy

"Yet each man kills the thing he loves" -- Oscar Wilde: De Profundis

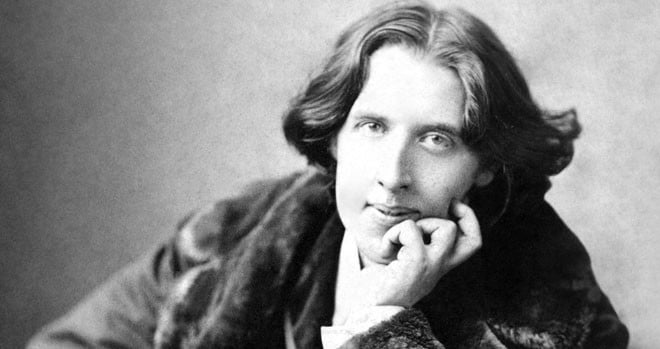

"De Profundis," originally a phrase from Psalm 130, literally means "out/from of the depths" is the title of Oscar Wilde’s 50,000 word letter written to his lover Lord Alfred Douglas. Wilde had been imprisoned on the charges of indulging in homoerotic desires.

John Sholto Douglas, the 9th Marques of Queensberry, and the father of Alfred Douglas had levelled the charges of sodomy against Oscar Wilde. At the time, these expressions of human desires were a crime in England and were described as "gross indecencies" in legal literature.

A poem titled "Two Loves" by Alfred Douglas was presented as a piece of evidence of an illegal relationship between the two men. The concluding line of the poem "I am the Love that dare not speak its name" indicates how the 19th century England looked at the relationship that was considered normal in Ancient Greece.

Oscar Wilde was imprisoned for three years with hard labour and, as a result, his health deteriorated considerably because he was accustomed to a comfortable life.

Towards the end of his prison term, Wilde wrote the letter that is now known as De Profundis. In the letter, Oscar Wilde tries to come to terms with his own flaws and outlines the transformation that has taken place within his psyche as a result of his imprisonment.

Despite giving a series of selfish and thoughtless acts of his interlocutor, Wilde blames only himself for letting himself be degraded and for succumbing to the excesses that led to his tragedy: "To deny one’s own experiences is to put a lie into the lips of one’s own life. It is no less than a denial of the soul."

In the letter, Wilde describes himself as the "lord of language" and as someone who changed the form of drama and transformed the genre. Despite his genius, he acknowledges his shortcomings and the effect it has had on his thinking and on his art and his reputation.

It is worth noting here that during a transfer from one prison to another, the onlookers, the so-called moral majority, spat at Oscar Wilde. This humiliation teaches him to distinguish between culture and nature.

Nature, he believes, will provide shelter for him after his release: "Nature….she will hang the night stars so that I may walk abroad in the darkness without stumbling, and send word the wind over my footprints so that none may track me to my hurt: she will cleanse me in great waters, and with bitter herbs make me whole."

The similarities between Wilde, Christ, and Socrates are clear throughout the text because all three of them were testing the limits of the hypocritical social order surrounding them.

Wild views the artist as an individual and as an individualist as a spiritual seeker: "What the artist is always looking for is the mode of existence in which soul and body are one and indivisible: in which the outward is expressive of the inward: in which form reveals."

Analysing his relationship with the moral order around him, Wilde describes himself as an antinomian: "Morality does not help me. I am a born antinomian. I am one of those who are made for exceptions, not for laws. But while I see that there is nothing wrong in what one does, I see that there is something wrong in what one becomes. It is well to have learned that." The basic idea behind antinomianism is that faith itself is enough and the moral code is superficial for those who have faith.

What is intriguing in the trial of Oscar Wilde is that Wilde, like Socrates, could have avoided the whole affair by moving to France but he rejected this option in the same way as Socrates rejected the offer of his friend Crito who comes to the prison to tell him that he has made all the arrangements for his escape and there is no need to drink hemlock.

Yet, by the end of his prison term, Wilde realised that the world around him was implacable. He changed his name to Sebastian Melmoth and moved to France. Socrates, it seems, was a greater moralist than Wilde because Socrates refused to run from the consequences of his intellectual inquiry even if it meant death.

On the other hand, Wilde was able to comment on the judicial and the carceral system and highlight the problems with them. Wilde’s life became an illustration of the eternal conflict between idealism and pragmatism -- between the martyr and the pragmatist.

The problem with idealism, as Ashis Nandy has theorised in his book The Intimate Enemy, is that the idealist leaves the stage empty for the dominant social order by ceasing to exist. The pragmatist does not leave the stage empty for the dominant forces to occupy and keeps persisting and creating new spaces for freedom by all means available.

After his release, Wilde lived his last years in France and corrected or revised his earlier plays. He did not produce any major work in the years of his exile: "I can write, but have lost the joy of writing." He spent his time wandering along the streets of Paris and spending his meagre income on alcohol, living in dingy hotels. Three years after his release, he died of cerebral meningitis that may or may not have been contracted during his stay at the jail.

Morality does not help me. I am a born antinomian. I am one of those who are made for exceptions, not for laws. But while I see that there is nothing wrong in what one does, I see that there is something wrong in what one becomes. It is well to have learned that.

Religion does not help me. The faith that others give to what is unseen, I give to what one can touch, and look at. My gods dwell in temples made with hands; and within the circle of actual experience is my creed made perfect and complete: too complete, it may be, for like many or all of those who have placed their heaven in this earth, I have found in it not merely the beauty of heaven, but the horror of hell also. When I think about religion at all, I feel as if I would like to found an order for those who cannot believe: the Confraternity of the Faithless, one might call it, where on an altar, on which no taper burned, a priest, in whose heart peace had no dwelling, might celebrate with unblessed bread and a chalice empty of wine. Every thing to be true must become a religion. And agnosticism should have its ritual no less than faith. It has sown its martyrs, it should reap its saints, and praise God daily for having hidden Himself from man. But whether it be faith or agnosticism, it must be nothing external to me. Its symbols must be of my own creating. Only that is spiritual which makes its own form. If I may not find its secret within myself, I shall never find it: if I have not got it already, it will never come to me.

Reason does not help me. It tells me that the laws under which I am convicted are wrong and unjust laws, and the system under which I have suffered a wrong and unjust system. But, somehow, I have got to make both of these things just and right to me. And exactly as in Art one is only concerned with what a particular thing is at a particular moment to oneself, so it is also in the ethical evolution of one’s character. I have got to make everything that has happened to me good for me. The plank bed, the loathsome food, the hard ropes shredded into oakum till one’s finger-tips grow dull with pain, the menial offices with which each day begins and finishes, the harsh orders that routine seems to necessitate, the dreadful dress that makes sorrow grotesque to look at, the silence, the solitude, the shame -- each and all of these things I have to transform into a spiritual experience. There is not a single degradation of the body which I must not try and make into a spiritualising of the soul.