John Keats’ writing style is lucid, and follows his thought pattern. It does not at all read like a stream of consciousness style

The art of epistle writing is an interesting one for it shows us what the writer is like to the person to whom he is writing that letter. As many as there are recipients, there are intimate bits of the writer scattered around which when put together present quite a wholesome picture of the man, or the woman, who writes letters.

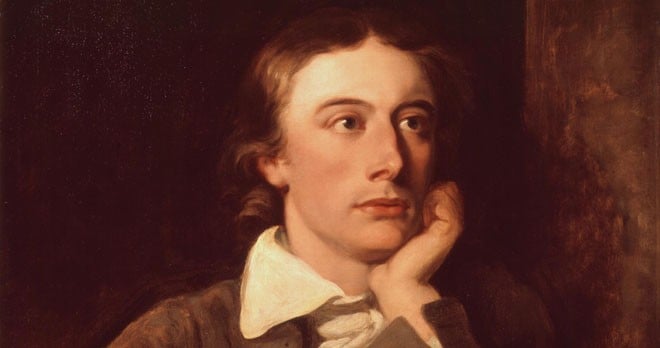

The poet John Keats in his short earthly sojourn wrote many letters and the one name that crops up is that of his inamorata, Fanny Brawne.

When he met her, he was captured by her liveliness and the two got engaged. Fanny’s mother held her consent to the marriage but agreed to the engagement. She hoped that Keats might be able to match the emotional bond with material prosperity equally strong. In 1818, they were engaged, in 1821, Keats died of consumption.

Keats wrote her many letters, some very passionate ones, but his full personality shines through in his letters to other friends and family -- probably because in letters to friends and family he is more multifaceted. When Keats was very ill at Wentworth Place, Fanny did not meet him but would often take walks below his window. The two regularly exchanged letters, and notes.

Interestingly, Keats’ ardent fans thought of Fanny Brawne as the lady without Merci for a long time, but in the end it was the letters exchanged between them that got published and this ousted the misconception.

In his letters, he writes about his everyday activities and then he interjects them with a snippet of observation like what sort of writing he is working at, in one of his letters he writes a lot of nonsense verse that goes like this:

‘Alas’ my friend! your Coat sits very well:

Where may your Taylor live’?’ ‘I may not tell --

‘O pardon me -- I’m absent now and then’

Where might my Taylor live? -- I say again

I cannot tell. let me no more be teas’d --

He lives in wrapping might live where he pleas’d

"You see I cannot get on without writing as boys do at school a few nonsense verses -- I begin them and before I have written six the whim has pass’d."

Keats has a sense of humour that even in his illness never deserted him. More than humour, it is a touch of irony that he never lets go off, in his last surviving letter to Charles Brown, he mentions that he has not written for a long time to a close friend. If he lives, he will correct the omission, if he dies, he will be forgiven in any case.

Not a dispute but a disquisition with Dlike, on various subjects; several things dovetailed in my mind, & at once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously -- I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason -- Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half knowledge. This pursued through Volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

In a long letter to Georgina Brown, Keats also comments on his own writing. He would never litter his poems with outlandish Greek and Latin inversions and annotations. To him, even as he was learning Italian, using the language to sustain his writing in English was not welcome at all. This indicates a purity of language in his poems and even in his letter he does not use a lot of foreign verse or idiom.

A very interesting observation on the mind of the man follows the comment on his friend Dilke and how he has changed in a letter Keats wrote in September 1819.

Keats declares that the sound intellect is not of a man who has made up his mind about everything, but of that man who let his mind be flexible, unmade, "let the mind be a thoroughfare for all thoughts," he says, "the stubborn arguers never begin upon a subject they have not preresolved on." Even if one manages to show them a point that is wrong, they still think the other person wrong and do not change their minds. Coming from a poet, this is good insight into the homo-arguing-sapien.

His writing style is lucid, and follows his thought pattern. It has a grounded sentence structure. It does not at all read like a stream of consciousness style with fragmented sentences or any other marked discourse points that show the writer actually thinking or associating freely.

With its lucidity intact, Keats’ letters are interspersed with the odd comic anecdote, with concern for family and friends; he exhorts one friend to wear warm jackets when travelling upon the steamer and on no account coming into the cold. He tells Fanny Brawne that he lives from one moment of seeing her to the next; he writes to his sister Fanny Keats about how his conscience smote him for not writing to her more frequently.

It is not the dejected lover who met La Belle Dame Sans Merci in his letters that we see. In his letters, Keats is a more rounded figure, a poet, struggling in his artistic toils and trying to take care of his orphan brothers and sister. He talks about getting up, dressing up, and then sitting down to write.

Even though it was a belief popularised by Shelley that Keats died because of unsympathetic literary reviews, the letters he wrote show him to be made of sterner stuff.

"My name with the literary fashionables is vulgar -- I am a weaver boy to them -- a tragedy would lift me out of this mess. And mess it is as far as it regards our pockets -- But be not cast down any more than I am. I feel I can bear real ills better than imaginary ones. Whenever I find myself growing vapourish, I rouse myself, wash and put on a clean shirt brush my hair and clothes, tie my shoestrings neatly and in fact adonize as I were going out -- then all clean and comfortable I sit down to write. This I find the greatest relief -- Besides I am becoming accustom’d to the privations of the pleasures of sense. In the midst of the world I live like a Hermit"

This, life as a hermit from the poet of sensation, is irony, indeed. In his last year when he struggled the most with his illness, he also wrote some of the most intense poems of his life. To Fanny Brawne, he mentioned in a letter that what he is leaving behind may not be substantial to grant him posthumous popularity, little did he know that his work would be one of the most analysed and examined in British literature.