Why at all was the private member’s bill, seeking national language status for nine languages, rejected by the National Assembly’s standing committee?

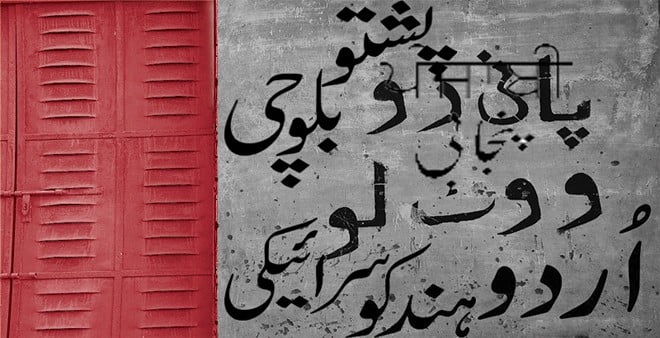

July 16, 2014 was yet another dark day for the advocates seeking a national status for regional languages. The bill presented by Marvi Memon of the ruling PML-N seeking national language status for nine languages -- Balochi, Balti, Brahvi, Punjabi, Pushto, Shina, Sindhi, Siraiki, Hindko -- and "all those mother tongues as deemed to be major mother tongues of Pakistan" was rejected by the National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Law and Justice with an overwhelming majority of 4-1. The only vote cast in favour was by PML-N MNA Sardar Amjad Farooq Khosa. Representatives of PPP, PTI, and JUI-F voted against the bill while MQM abstained.

The bill is not the first attempt to raise the status of indigenous languages, commonly called ‘regional’ languages, to that of a national language.

The issue of deciding Pakistan’s national language has been contentious since the 1940s. Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared Urdu to be the language of the state after the partition. However people of East and West Pakistan, who spoke a variety of languages, felt it relegated their mother tongues to a second-class status. Bengalis felt especially aggrieved because they constituted the majority portion of the population.

Though Jinnah clearly said on his visit to Dhaka in 1948 that the people of Bengal could choose their language for official use in the province, the sense of injustice continued and triggered the Bengali Language Movement. In 1952, a group of students who had gathered in Dhaka to protest for recognition of their language were shot at by the police. Many students died on February 21 which is now celebrated by the UN as International Mother Tongue Day.

The movement eventually culminated in Pakistan adopting both Bengali and Urdu as the state language in the Constitution of 1956.

Over the past few decades, and especially during the current phase of democratic governance, efforts to get other regional languages to be declared as national languages have continued.

During the deliberations on the 18th amendment in 2010, ANP Senator Haji Muhammad Adeel and ANP President Asfandyar Wali Khan wrote to the chairperson of the 18th amendment committee seeking national language status for a few regional languages. But the proposal, Senator Adeel says, was opposed by other parties and never saw the light of the day.

Senator Adeel tells TNS that in lieu of national languages, ANP also asked for the languages to be recognised as "Pakistani languages", presumably for symbolic value, but that request was also rejected.

In 2011, Marvi Memon, who was then a member of National Assembly on PML-Q’s platform, moved a bill seeking national status for regional languages. That bill was rejected, as was the one she presented three years later in 2014. Senator Adeel has also submitted a bill to the Senate to the same effect, though the languages he proposes to be given national status are less in number than what Memon suggests. The bill has yet to come up for debate.

Significance of national language

Speaking to TNS, Mushtaq Soofi, President Punjabi Adabi Board, says that though the constitution gives provinces freedom to take measures to promote languages spoken in their jurisdiction, the languages need to be recognised by the federal government for support and its promotion. "In Sindh", he says, "Sindhi is recognised as an official language and has gotten its rights, but Seraiki, which is also spoken in the province, has no rights and gets no support or aid for its development."

According to Sindhi fiction writer and playwright Abdul Qadir Junejo, Sindhi’s official status is not just on paper but is practically reflected at judicial and all administrative levels. In fact, Junejo says, he is not worried about the future of Sindhi because Sindhi language media, both print and electronic, is strong in the province. Similarly, he says, literature is thriving in the province with over a dozen books being published in the language every month. In this way, the demand of Sindhi to become a national language gains more of a symbolic value.

Other languages, though, need more support from the government.

Thus, though like Sindh, the provinces can take up measures to declare their traditionally dominant languages as official languages, it will be at the expense of ignoring other regional languages spoken there. It is therefore important to recognise these languages on the national level.

Herein lies the crux of the matter. Demarcation of provinces and changing demographics over the decades now mean that languages are no longer relegated to one particular region. For example, according to Saleem Raz, Secretary General Anjuman Taraqqi Pasand Musanafeen Pakistan, the largest population of Pashto speaking people in the world is not in Peshawar or Kandahar but in Karachi, Sindh.

In India, for example, though the official languages of the Union are Hindi and English, the eighth schedule of the constitution lists 22 scheduled languages. And according to the Official Languages Resolution of 1968, the government of India is bound to develop a programme for the "coordinated development of all these languages [at that time 14 in number], alongside Hindi so that they grow rapidly in richness and become effective means of communicating modern language".

Soofi believes that recognition of these languages at the national level will also increase the sense of unity among the people and allow them a sense of ownership of their nation-state. Raz agrees: "Pakistan was made by combining people of various nations and traditions. All these nations (aqwaam) should be given the same recognition by the state accepting their cultures and languages".

Countering the narrative that the regional languages are and should be confined to their "region", Abdul Qadir Junejo says "every language originally belongs to a region". If the state disallows major languages to become national languages, he says, then it can be inferred that it doesn’t consider those people part of its nationhood. "We have nothing against Urdu being the national language," he says. "But if a country as small as Switzerland has four national and official languages," he argues, "why can’t we?"

Professor Shah Muhammad Marri, Baloch historian and intellectual, has a different view. "Why are you focusing on the language issue," he questions while talking to TNS. According to him the situation of 1973 is very different than of 2014. "Over the years, commonalities among people have shrunk and enmity seems to be the only common thing left," he says. "The Baloch are fighting a bigger war on social and political levels," he goes on to say, "they have moved further and this [language] war has become a small war now."

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa’s initiative

In its tenure, the ANP-led government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa passed the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Promotion of Regional Languages Authority Act of 2012. Under this Act, a regional languages authority (RLA) was to be set up for the purpose of not only promoting the regional languages at educational institutions, but also given support in "publication of dictionaries, encyclopedia, reference book, scientific literature and periodicals" (Section 6 subsection 2-c), and translation of "technical terms in science, home economics, humanities and commerce subjects" (Section 6 subsection 2-d).

The Act seemed promising in advancement of regional languages, but three years after its enactment, the RLA is still to be set up. Senator Adeel blames the current PTI-led government for reversing the efforts made by his party. "Their primary interest is introducing English in schools," he says.

Establishment of National Languages Commission

So why was the bill rejected by the standing committee? Justice (retd) Raza Khan, Special Secretary of Ministry of Law, Justice and Human Rights, tells TNS of factors which contributed to the ministry’s opposition to the bill.

"The basic purpose of introducing a bill by an MNA of the ruling party is to have the party’s support for it," he says. "The proper procedure would have been for Ms Memon to present it in the parliamentary party meeting and her party would have approved it in line of its manifesto."

According to Justice Khan, it was suggested to Memon that before seeking constitutional amendment, the first step should be to establish National Languages Commission which her party has committed to in its manifesto. The commission would then take stock of the languages being spoken in the country and devise criteria of how many people speak and understand a language for it to be constitutionally accepted as a national language. "For example," Justice Khan says, "the commission may set the criteria that a language spoken by 50 per cent of the people can be considered a national language." However, Memon showed inability to withdraw the bill so it was rejected.

Khan goes on to say that our experience with multiple languages has not been very pleasant. "In the constitutions of 1956 and 1962, both Bengali and Urdu were declared national languages, and on the basis of that two nations were created."

"However," Khan emphasises, "if the commission is established that recommends a certain language to be made a national language and if the bill is moved as a government bill, we will not object to it".