With the Punjab entering a new phase of modernisation during the first half of the nineteenth century, a new system of education was developed with a good admixture of Oriental and Western learning

When the British first annexed the Punjab there was a local system of education, usually linked to the local Hindi, Muslim or Sikh religious institutions, or patronised by local strong men. Dr Leitner, the first Principal of Government College Lahore and the founder of the University of the Punjab, noted in his History of Indigenous Education in the Punjab:

"…there is not a mosque, a temple, a dharamsala, that had a school not attached to it…There were also thousands of secular schools, frequented alike by Muhammadans, Hindus and Sikhs…there was not a single villager who did not take pride in devoting at least a portion of his produce to a respected teacher…In short, the computation gives us 330,000 pupils…in the schools of various denominations who were acquainted in reading, writing, and some method of computation."

However, this picture of indigenous education is sharply contrasted with the experience of Rev’d Lowrie, who while visiting the court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1835 noted a dismal state of education in the Punjab. Lowrie noted:

"It is not probable that one person of every hundred is able to read. Of those who can read, four-fifths, probably, only read the Persian. A few of the Sikhs read the Gurmukhi; and a few of the Cashmerians, perhaps, read Kashmiri…Of those, who acquire a knowledge of their written language, few learn anything beyond the simplest rudiments. There are scarcely any books, and there are none adapted for purposes of instruction. The schools are very few, and under worst management. Sometimes the teachers are paid by religious persons, or else, as is most common, are themselves religious persons…Everything is learnt by rote. In the Mussulman schools, for the higher scholars, one of the first things is to teach the boy to read the Koran in Arabic, without even pretending to teach him the meaning of a single word."

As an astute observer, perhaps Lowrie’s assessment is nearer the actual conditions of the Punjab during the first half of the nineteenth century. While there might be a number of indigenous schools associated with religious establishments, or endowed by local personages, their primary emphasis was on religious instruction, which though important, if not properly understood and explained, does not even serve this narrow purpose. With the Punjab entering a new phase of modernisation a new system of education had to be certainly developed.

Initially, the British supported a system of incorporating a mixture of indigenous and local education, known as the ‘halkabandi’ scheme which had been previously successfully tried in the North Western Provinces. Under the halkabandi scheme, Dr Allender describes: "at the headquarters of each tahsil, a government tahsili school was established and its instruction was linked in part to the communal nature of the surrounding village schools, whether Hindu, Muslim or Sikh." Hence under this scheme several indigenous schools were linked to the main tahsili school, with little expense to the government and the beginning of the creation of a good admixture of Oriental and Western learning. By 1854, there were over three thousand indigenous schools attached to 62 tahsili schools in the North Western provinces, exhibiting it success.

The Department of Public Instruction was set up in the Punjab in 1855 with William Arnold as its first director. Already the Chief Commissioner, Sir John Lawrence, and his colleagues, Montgomery and McLeod, had knowledge of the halkabandi system, and were in favour of its adoption at least as a stepping stone measure in the Punjab.

Assuming office in January 1856, Arnold immediately set upon devising a halkabandi system for the Punjab. Rs 3 lakh were allocated to the department from imperial revenues in 1856-7, and Sir John Lawrence obtained for Arnold a free hand in developing his plans. By 1858-9, Arnold had established 142 tahsili schools and 2,029 halkabandi village schools, which nearly 45,000 pupils and a great mix of vernacular languages used at the primary level. However, when Sir Robert Montgomery became the Chief Commissioner in 1859, he abandoned the halkabandi system, because as Dr Allender notes, "…by the late 1850’s, this European perception of indigenous education was to be re-imagined as Punjab government officers now aimed to champion the validity of government schooling and sought to discredit local efforts."

In 1860, Captain Fuller replaced Arnold at the Department of Education and the whole educational setup was revamped. The halkabandi schools were discouraged in favour of schools under increased government control. There was also a general change of focus towards popularising Urdu and English in the schools, and more schools were now to be established in the towns as compared to the villages. Dr Allender contends that Sir Robert Montgomery "…he hoped to anglicise the whole curriculum by gradually introducing instruction in Persian Urdu and then in English and ignoring, for the most part, halkabandi village instruction in the local languages."

The establishment of schools focused on imparting mainly Western education of a higher standard created a number of problems for the government, and the promotion of education in general. First, was the concern that most students at these schools only wanted an education for the sake of obtaining government favour and employment. Even Lowrie noted: "…that the most weighty motive to a native’s mind for seeking knowledge of our language is the hope of pleasing his European superiors, and of deriving some sort of advantage from their favour."

A missionary report hoped that "…that time will come when good education will be valued for its own sake; till then we must labour between discouragement and hope." Secondly, while there was great eagerness to learn English, most pupils in endeavouring to learn the language not only failed to master it, but also did not sufficiently master the vernaculars. A note from the Government of India stated: "A doubt may perhaps occur, whether the Punjab government, while rightly encouraging the study of English, may not be losing sight in some degree of the necessity of guarding against the tendency which has been found so prejudicial in Bengal viz: of substituting a smattering of English, for a sound practical education conveyed through the medium of the Vernacular."

Therefore, the success of an English medium institution depended not only on the interest of the incoming pupils -- which in the circumstances was not great beyond hope of government favour -- but also instruction, where the school had to give sufficient instruction to its pupils so that they could master the new language.

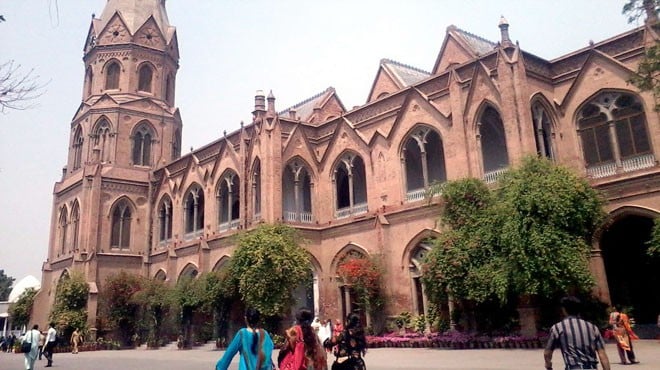

When the Lahore Mission School opened on December 19, 1849, as the first English medium institution in the Punjab, its work was already cut out. It entered unchartered territory where there were strong indigenous educational institutions, and where the system of English education only began to appear in the 1860s. The American Presbyterian missionaries were ahead of their colleagues in other institutions in sensing the rise of English as the language of the empire and strove to educate the students of the Punjab in the tongue long before the government -- and even other missionaries -- ever attempted to. The Punjab was changing and the American Presbyterian Mission at Lahore was now at the forefront of leading the charge in the field of education.