Pakistan must compete for limited pockets of energy surplus in the region for inclusive and sustainable economic growth

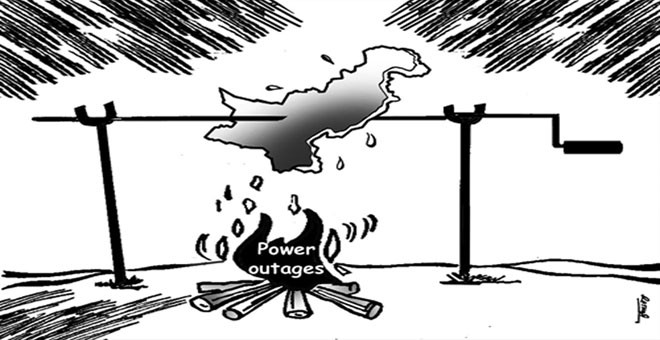

Pakistan’s power shortages may not see an end very soon. A shortage of 5000 MW in power sector, policy uncertainty, governance challenges in generation and distribution companies, technical losses, theft and an overall high cost of producing power have resulted in an average annual loss of 2-3 per cent of national income.

The petroleum crude and products are now contributing to a third of Pakistani imports. This will continue to threaten the country’s balance of payments as oil prices become volatile due to the crisis in the Middle East, particularly in Iraq and Syria. The circular debt in the energy sector will continue to haunt us. The government will accommodate this debt through distortive subsidies and federal transfers to the power sector.

The government’s narrative on energy talks of medium to longer term solutions with assistance from bilateral and multilateral development partners, which means more debt. With mounting debt burden, one would have liked to also see a medium to longer term debt management strategy in the Finance Minister’s budget speech. It is also still unclear from the budget how the government plans to finance the promised infrastructure in the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline and Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) Pipeline.

There are some institutions at the periphery that talk about environment-friendly renewable energy. Sadly these institutions lack constituency within the current federal or provincial governments. Recently, advocacy for developing shale resources has been stepped up. What makes us think that that this opportunity will be utilised, when 18000 MT of coal, 33 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, 324 million barrels of fossil oil, 50000 MW of hydro power is still waiting to be explored.

What is it that the government is not telling us? First, it will continue to increase power and gas tariffs and indeed the burden will fall on the middle and low income groups. Second, the government will continue to provide hidden and cross energy subsidies through tax payers’ money and third, the government has limited control over technical losses, implying that transmission and distribution losses and theft of electricity will continue.

Now let us come to a completely neglected possibility in the energy sector. Eastern African sub-region, an energy-deficient region, is now engaging in regional energy trade to bridge its deficit. Since 2008, Latin American countries are pursing regional energy trade possibilities to bridge their demand and supply gap. The power sector integration is at a fairly mature state in the gulf countries.

Here is what is happening in our own region. An energy hungry India will now be supplied hydro power by Nepal. Hydropower from Bhutan has now become a centerpiece in Bhutan-India ties. More recently Bangladesh and India have signed an agreement which will ensure exchange of power through grid connectivity between the two countries and joint investment in power generation and capacity development of Bangladesh Power Development Board.

The Power Grid Corporation of India and Ceylon Electricity Board in Sri Lanka will undertake construction of submarine cables which will allow transmission of 1500 MW between the two countries.

India maintains a longer term contract with Qatar for supplies of both oil and gas. Similarly, India in a bid to secure its future energy needs has entered into a long term LNG contract with US and Russia. It is engaging with China for possible pipeline from Russia to India that will pass through China. In March this year, India has started negotiations towards Iran-Oman-India deep sea gas pipeline that will transport 31 million cubic meters of gas/day to India.

As Pakistan rarely learns from its eastern neighbours so we may turn to the west of Pakistan. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have large surplus in generation. Afghanistan, therefore, imports electricity from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Additionally, Afghanistan is also making use of occasional electricity surpluses in Iran and Turkmenistan.

Despite western pressures, Turkey continues to import oil and gas from Iran. In 2013 alone Turkey imported 10 billion cubic meters of gas from Iran. Currently, Turkey is also taking 100,000 barrels/day of Iran’s crude. In 2013, Armenia and Iran decided to build a hydro-electric power plant in their bordering region. North-South railway (Iran-Armenia) is also proposed which will increase mobility of energy resources. Not surprisingly, the interdependencies created by energy trade are cementing overall bilateral relationships in Central and South Asia.

How sharp is Pakistan’s energy diplomacy? Let us start from Iran. Unlike Turkey the current and the previous governments have been hesitant to openly pursue energy cooperation with Iran (owing to fears of opposition from the US). Apart from the 100MW of power coming to bordering areas of Balochistan all other plans are still a big rhetoric. Pakistan still has to build 781 kilometres of gas pipeline for honouring its commitment signed under Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline.

How serious is Pakistan in pursuing TAPI? Unfortunately, Pakistan has not sought any guarantee from Turkmenistan and transit countries which could ensure certain gas supplies. In fact, Chinese and Turkish intent to purchase gas from Turkmenistan and possible construction of Trans-Caspian pipeline for Europe will soon result in the end of TAPI negotiations. It is likely that US after its exit from the region will also not put its weight behind the materialisation of TAPI.

These developments should be worrisome for a country which has already consumed 40 per cent of its gas deposits. The remaining reserves may only last another 15-20 years. The current production of gas will drop from the present 4 billion cubic feet per day (bcfd) to 2.53 bcfd by 2020.

Let us now turn to Central Asia-South Asia (CASA) 1000 project where Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan plan to export 1300 megawatts of power to Afghanistan and Pakistan. The multilateral development partners including the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and Islamic Development Bank have agreed to provide financing to Pakistan for this project.

However, once again, institutional inertia can take this opportunity away from Pakistan. Given that there are no guarantees at the moment, nothing stops Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan to change their positions. Already there are voices in Kyrgyz republic suggesting greater cooperation with China, India and Russia. These countries are also willing to provide financial assistance in faster development of Kyrgyz Republic’s energy sector.

It has been reported that Dataka-Kemin power lines would allow Kyrgyz republic the export of power to China and Kazakhstan at more attractive terms than Afghanistan and Pakistan. China and Tajikistan have also signed a gas pipeline deal. Already Beijing is heavily investing in Tajikistan’s mining sector. Similarly, China has announced USD 1.4 billion for Kyrgyz part of Central Asia-China gas pipeline.

Those institutions and countries willing to connect Pakistan with regional energy markets are not much concerned with security threats and obsolete infrastructure. They are, however, concerned about our inability to improve energy governance, ensuring independence of energy regulators and an uncertain pricing regime. Expanding energy supplies is of no use if transmission and distribution networks have leakages. These are the circumstances where payback in power sector becomes difficult for a government, multilateral partner or even a business entity entering into a public private partnership.

Pakistan should quickly understand that energy diplomacy matters for inclusive and sustainable economic growth. We need to get our act together and compete for limited pockets of energy surplus in the region. The standing offers of ‘trade in energy’ by Afghanistan, Iran, India, China, Tajikistan and Kyrgyz Republic should be seriously pursued.