A young documentary filmmaker celebrates the emancipation of four outstanding Pakistani women in America.

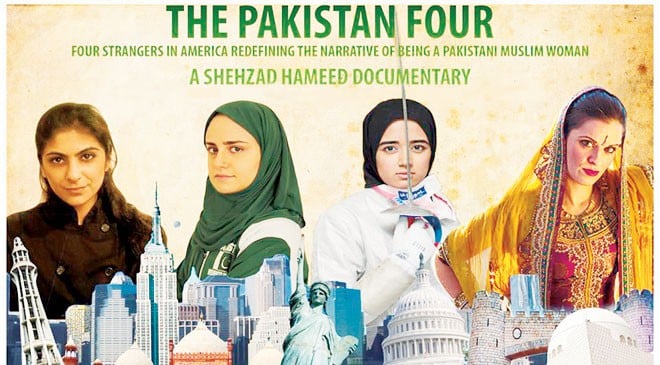

A female fencer alone would make a good enough singular subject for a documentary. But when that female fencer is of Pakistani origin, it is bound to make people sit up and take notice. When that Pakistani female fencer is a hijab-donning practicing Muslim in America, who quit Wall Street to follow her more fulfilling fencing dreams, the documentary becomes an eye opener. This title-winning fencing champion, Hareem Ahmad, is joined by three other equally extraordinary Pakistani American women in this inspiring Shehzad Hameed Ahmed documentary titled The Pakistan Four. It charts their stereotype-defying journey of passion and perseverance, as they overcame familial disapproval and societal prejudice to pursue their dreams, despite the baggage of every label attached to them – female, Pakistani, Muslim.

Interestingly, all of the women chose vocations that are typically male-dominated. Fatima Ali fostered the desire to become a sous chef despite her family’s disapproval of her career choice, and eventually went on to win top prize on reality cooking show, Chopped. Kulsoom Abdullah, amidst a well publicized media debate and quiet opposition from an anxious mother, famously bent the weightlifting rule book to be permitted to wear covered attire in championships. The fiery standup comedian Nadia Manzoor drew from her own strict upbringing to talk about thorny themes like family honour in her play Burq Off! The Pakistan Four brings to the fore people and stories that have always existed, but are left out of mainstream narratives.

"We’re all responsible for this," said the director Shehzad, who has worked as a broadcast journalist prior to securing a Fulbright scholarship and subsequently embarking on his documentary filmmaking career. "We don’t tell those stories. Journalists think positive stories don’t sell."

"In America, there has been a lot of negative media about Pakistanis and Muslims, and I had gotten tired of it," continued Shehzad. "Pakistan is a really diverse country, and I felt it was my responsibility to convey the many, different stories that emerge from the land. I was very inspired by Malala and felt compelled to do something to change the image of Pakistani women."

It all started with a stumble across fencer Hareem’s Facebook page. Intrigued, Shehzad fired off a message to her and was on the phone with her in an hour. "It’s really important for characters to want to tell their story," Shehzad shared, "…and Hareem really wanted to tell hers." Originally, Hareem was the sole subject of the documentary, but chance meetings with Nadia and Fatima in New York broadened the documentary’s scope. Then, a friend told him about the hijab controversy sparked off by Kulsoom’s efforts, and she agreed to be a part of the documentary when contacted.

While The Pakistan Four would force the foreign viewer to rethink stereotypical preconceptions of oppressed Muslim women – "Do these women really exist?" was the typical reaction of the film’s American audiences – and introduce local viewers to a world of possibilities for women, it also confirms, again for the foreign viewer, that Pakistani households stifle female ambition and merely focus on breeding good wives. One couldn’t help but defensively wonder if there wasn’t at least one family who was supportive of its daughter’s dreams?

Shehzad reasoned, "The thesis of the film was true across Pakistan and its cultures," he shared. "Hareem’s family is from Bahawalpur, Kulsoom’s from the Frontier, Fatima’s from Karachi and Nadia’s from pre-partition Bangladesh. All of them hail from different parts of Pakistan and belong to different social classes. It doesn’t matter with gender barriers, they exist across the board."

"This is really not a Pakistani problem," continued Shehzad, "It’s an immigrant problem." Pakistan is a country that’s on the move; it keeps up with the times. These immigrant communities went to the US in the 1980s. They were very insecure: they wanted all the benefits of living in their host country, but were not accepting of its culture." Hareem calls it living in a snow globe of 1989 Pakistan.

That begs the question of how Shehzad even managed to get their consent to film them in their homes. "Well, first, I needed to cross gender barriers myself to gain the trust of my characters. Their families were apprehensive too, for instance, Fatima’s mother was skeptical of being in the media and declined to participate. But eventually, the other families believed in me. It was difficult because I was living with them and eating with them while shooting the documentary, but they were very enthusiastic about the end result. Even when I was working on the edit, I kept getting phone calls to ask how it’s going. In the end, Kulsoom’s and Hareem’s mothers were all praise for it."

The Pakistan Four is now making its way to the Fresh Film Festival in Prague in September, and will be the only film to represent Pakistan. What the documentary is really showing is everyday stories – four women doing what they want to do with their lives – but mainstream media is starved of those. It’s only when a change in narrative occurs at this basic level that misconceptions and prejudice can be vanquished.