Pran Nevile talks about the ‘incomparable’ Lahore, its singers, artists, dancers and his fascination with the British Raj

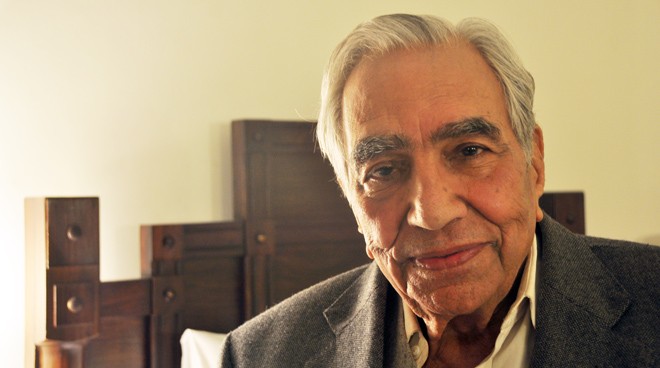

By any writer’s standards, Pran Nevile’s career has been enviable. He has written several of the strongest books on the British Raj, of the past twenty years. But because of the ponderous political divide between India and Pakistan, it’s only now that he’s come to be recognised. Born in Lahore in 1922, he served a long career as a diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service and the United Nations before turning to writing.

He has a complicated face, one that can flash a smile of complacency but just as easily offer something more disturbing and Jesuitical; it is the visage of someone whose life is not all affirmation and whose secrets are not for sale. His books are textured by contradictions, limpid but dark inner currents, and an unpredictability that echoes Sartre’s concept of existential freedom. There is no such thing as a ‘typical’ Nevile, but he is best as someone who can reconcile opposites: impulsiveness and practicality, great heart and shrewd opportunism.

The interview occurred in the quiet of his Gymkhana room, with an earnest literary crowd gathering ten feet away in the lounge.

The News on Sunday: Of course, you were born in Lahore and studied at GovernmentCollege here, but what is it that makes you a quintessential ‘Lahori’?

Pran Nevile: I was born here, brought up here, and educated here -- I consider myself a part of Lahore, and conversely, Lahore, a part of me. My attachment to my hometown is unique -- something that I can’t explain in words because the city itself defies description and definition. The city has to be felt and experienced. I spent my childhood, my boyhood and my early youth up to the twenties here. Six years that I spent at the Government College were the most fascinating period of my life when I saw the best of friends, culminating in a life-long friendship with Saeed Ahmed. A column titled, ‘Saeed and Pran’ written by his granddaughter, Zuleikha, appeared in The News with photos et al, four years ago, commemorating our friendship. I met him after fifty years (and those fifty years of separation seemed like fifty minutes) when I landed in Lahore in 1997 under the impression that Saeed was no more! Somebody had passed on a piece of erroneous information to me. When I came here, I asked my friends that I wanted to meet his family. They found out that Saeed was still alive. (I had already dedicated my book on Lahore to him, in memoriam). It was an unforgettable meeting -- a unique incident etched on my mind. He was supposed to come to Delhi and stay with me in December 2000, but he passed away two months earlier.

So what draws me to Lahore? I feel so much at home here even all by myself. Walking along the Mall, I can still recognise the landmarks that I left -- DingaSinghBuilding, ShahdinBuilding, Ferozsons, Dayal Singh Mansions, the High Court, E Plomer -- they are all there for the last one hundred years. From Charing Cross to the GPO, it’s much the same save a few new structures. I go to Anarkali Bazaar and to the WalledCity where I spent my childhood. I’ve been practically all over the globe right up to Latin America but nothing quite compares to Lahore. On the contrary, I have never felt at home in Delhi -- it’s a topsy-turvy mixture, a miniature India. And it’s not a city anymore.

TNS: In your opinion, why should Lahore be given preference over any other city?

PN:Lahore is far more important because it was the capital of Mughal India before Delhi was even born. Akbar came to Lahore from Agra -- it remained the Mughal capital for more than twenty-five years -- and all the monuments that you find here were constructed before Delhi was built. Delhi became the third Mughal capital while Lahore was the second with a romantic milieu. Lahore was the centre of music, art and culture. The greatest singers -- Bade Ghulam Ali, Mukhtar Begum, Inayat Bai Dherowali, Tamancha Jan, Gauhar Jan, Noorjahan, Shamshad Begum, Munawwar Sultana -- all these twentieth century greats came out of Lahore. Surraya was born in Lahore and so was Khursheed. And the great composers -- Khursheed Anwar, Rafiq Ghaznavi, Ustad Jhandey Khan, Feroze Nizami, Baba Chishti, Amarnath, Gobindram, Husn Lal Bhagatram -- all came from Lahore. Music being my passion, I have been organising musical functions in memory of all great singers, poets and composers of yesteryear for the last 10-15 years. I’ve also researched on the Indo-Pak musical journey -- the common heritage of our music.

The very idea of making films on the same subject has been shared by both countries. (There are at least 30-40 titles identical in both places). India made Anarkali, so did Pakistan; Pakistan made Umrao Jan Ada, Qaidi and Tehzeeb, so did India. After 1947, borrowing the same theme, songs were also shared: if "Dil to kya cheez hai jan tujh pe nichhawar kar doon" is the Pakistani version, the Indian version is "Dil cheez kya hai aap meri jan leejiye". Or the Indian copy of Tasawwur Khanam’s "Agar tum mil jao zamana chhor dain ge hum", etc.

I’ve paid tributes to artistes like Noorjahan, Iqbal Bano, Malika Pukhraj, and Reshma -- the greatest folk singer of the subcontinent. This is our common heritage. Lahore is not just about literature but about almost everything, even visual arts. Even during Ranjit Singh’s time, there were artists the calibre of Imam Bakhsh Lahori who painted murals and illustrated French books in the nineteenth century. There were Allah Bux, Amrita Shergil and B C Sanyal in my time.

Then there was dance! From the early 1900s until the next twenty-twenty five years, the missionaries raised propaganda against dance, banning it from public display. Two Americans came to study dances of North India, and the only place where they could watch the best of classical performances was Lahore where the great Kathak maestro, Pt. Hira Lal, adorned the stage. Zohra Sehgal, who’s now 102, ran the dance school in Lahore in the 1930s. And the first institution of classical music, in the quest to revive North Indian music, was established in May 1901, in Lahore by Vishnu Digambar Paluskar. As a student I used to go there on my bicycle on Ravi Road.

TNS: With an illustrious career in foreign service, why did you decide to devote your life to arts and culture?

PN: I was an internationally-recognised expert on the Soviet Bloc. I spent four years in Poland, four in Yugoslavia, and five years in Moscow, Russia. In 1989-90, the Soviet Empire collapsed and the Communist Block vanished from the scene. I lost my constituency, and my expertise became redundant. It was at that point that I decided to contemplate and pursue my passion for music and art. So, I became a freelance writer. I had no interest in bureaucracy; I had never sought any position after retirement when I could have landed a job in the corporate sector, easily.

First came the passion to write a book on Lahore, followed by the fervour to write a book on the dancing girls of India -- the great performing artistes -- and subvert the notion of ‘kothey wali’. Lahore: A Sentimental Journey was printed in 1992, and my work, Nautch Girls of India: Singers, Dancers and Playmates came out in 1997. It took me seven years to research and write it. It was printed in Italy with illustrations I had collected from all around the world. I travelled to the States and across Europe, and came back with illustrations seen for the first time in print.

I am also an art historian, and have five coffee table books under my belt. In addition, I did extensive research on the British artists who came to India during the 1880s and 1890s. It is basically a portrayal of India -- men, women, landscape, the Raj --but like Qurratul-ain-Hyder’s Aag ka Dariya, I am only known for Lahore: A Sentimental Journey.

TNS: What got you interested in the Nautch Girls of India -- was it an attempt to dignify them or the quest to pay tribute to a lost culture?

PN: It was my gratitude to those performing artistes for preserving the art of dance for centuries. We should be indebted to them, and pay homage to them for sustaining a tradition rather than run them down as ‘fallen women’ which is what the missionaries taught the West-educated Indian citizen. I tried to place them in an historical perspective.

I also wished to include all those sketches and paintings that were made by the European and Indian artists, commissioned by the Europeans, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The term ‘nautch’ is derived from ‘naach’ by the British. As a matter of fact, when the British were stationed in Calcutta, they heard the Bengalis pronounce ‘naach’ as ‘noch’, hence ‘nautch’. For my book, I went through contemporary literature, art books and whatever had been published on the subject, including observations made by the British scholars, travellers, civilians, and the army officers, who’d witnessed those performances. They were also patrons of the dancing girls in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

One cannot say if the nawabs and the rajahs were slandered by the book’s reception being both patrons and spectators but the renowned dancers, and especially the feminists, did not respond to the book in the affirmative upon a casual glance. The book was finally launched by Khushwant Singh with a performance by one of the most accomplished female dancers, Swapna Sundri.

TNS: What exactly has been your point of fascination with the British Raj?

PN: I belong to that period, and that is what fascinates me about the Raj primarily. While I was researching towards my book on the dancing girls -- research was mainly carried out abroad because there’s practically nothing on the subject in libraries in India -- I went through all those published and unpublished journals that were penned down by the British scholars, travellers, bureaucrats, and army officers, and culled information from them. Along with that, I requested the authorities to help me accede to their entire collection. At the British Library, they take time -- they would show only twenty or so paintings in one go, for instance. I had to go there several times to view the collection and make a selection. No scholar had ever bothered to go through those sketches and paintings before me. I got transparencies made, and it inspired them so that they decided to have postcards made for the library based on my selection of images.

After that, I thought what should I do with the material I have selected? That is when portraits of Indian women before the age of camera dawned upon me. That gave birth to the idea of bringing out another tome, Beyond the Veil: Indian Women in the Raj that triggered my interest in how the British lived in India, the social and cultural life of the Sahabs, their interaction with the Indian women, the Bibis, and the Anglo-Indians.

I did research Raja Deen Dayal’s photographs but did not include them in my study because they were not quite compatible with my writings. On the contrary, I discovered Frank Carpenter’s collection of 400 photographs of India lying away in boxes that were opened for the first time in the 1990s by me at the US Library of Congress. Span magazine, published by the US Embassy, commissioned me to write three articles, acknowledging me editorially for my discovery. My next book, India through American Eyes: 100 Years Ago is again based on the material I had gathered from the library, recording first American impressions of India.

TNS: What drew your attention to K.L. Saigal, of all the singers of the time, so much so that you decided to dedicate a biography to him?

PN: Being a music composer, Pankaj Mullick groomed Kundal Lal Saigal. Saigal had a heavenly voice, and what people don’t know is that he was a poet too. In addition, he was a composer -- all those 78 rpm records of ghazals do not bear the composer’s name because he composed and selected the ghazals himself. He was a Punjabi from Jullundhar whose father had a job in Jammu as a Tehsildar in G&K Government. As a child, I would listen to Master Bhagwandas -- another great singer in Hindi films -- but when I heard Saigal’s first song from 1933-34, ‘Jhoolna Jhulao Ri’, I felt it was a voice from the heavens. I was enchanted, knowing nothing about melody or raga. I was so fascinated that when I could afford it after I started to earn, the first thing I bought was Saigal’s 78 rpm record.

When I was abroad as a commercial counsellor, I helped HMV in promoting the company, and advised them to take out two records based on their collection of K L Saigal’s repertoire: one comprising his film music, and the other featuring devotional songs and ghazals. In my biography of Saigal’s, I have included the correspondence between myself and the Gramophone Company of India based at Dum Dum, Calcutta, in 1965.