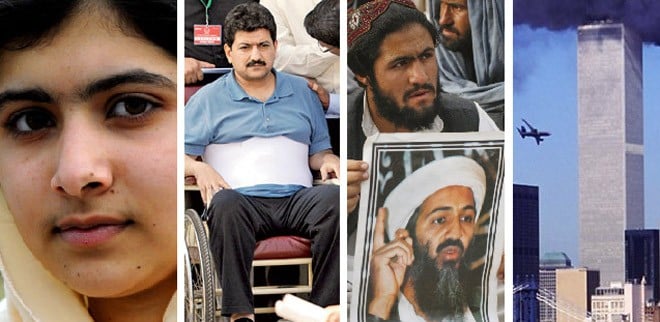

While the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan’s vicious assault on the Karachi airport was still underway, the same television networks that were beaming it into our living rooms, also started speculating about the Indian involvement in the episode. Conspiracy mongering has become a manifestation of the morbid denial and rationalisation of the problems largely of Pakistan’s own making and helps sustain an artificial self-respect while keeping the genuine national concern and anxiety -- which normally should have kicked in -- in check or at bay.

The national pastime of weaving conspiracy theories perhaps has its origins in how the newly independent Pakistan defined the state’s creed and its domestic, regional and international priorities. In the words of Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the British, ostensibly in collusion with the ‘Hindus’, gave him a "moth-eaten" Pakistan. A sense of victimhood in the Quaid’s words is unmistakable. There, indeed, were real issues emanating from the 1947 partition, such as the Radcliffe Line, division of assets and liabilities, and the communal rioting that contributed to this sense of betrayal.

The Baloch and Pashtun areas, which were induced to join the union through coercive and controversial tactics, respectively, were never treated as equal by the ostensible ‘core state’. They were viewed, instead, with suspicion. Rather than dealing with their political grievances in a mature manner, the state felt insecure vis-à-vis the Baloch and Pashtun nationalists.

A realistic assessment would have been that the partition was going to be a very messy divorce, which entails all the bickering and bloodshed that it did. Unfortunately, the thought that became the Grundnorm of the new country was part reality and part myth. The country’s earliest leadership chose to frame its problems with India, and within their own new borders, in an ideological context, the bedrock of which was the Two Nation Theory (TNT).

While the TNT politically proclaimed that the Muslims of India were a national entity distinct from their Hindu compatriots, the theory’s undertones implied that they were also a ‘superior’ nation. The twin delusions of paranoia and grandeur that Pakistan labours under today have their origin in this superiority complex coupled with a sense of getting wronged by an ‘inferior’ people. The acronymic neologism Pakistan -- the land of the pure -- is perhaps unique in the world even today.

Combine that with the other descriptions used for the country, such as Mumlikat-e-Khudadad, i.e., a God-given state and the complex becomes a dogma replete with a claim to being the divinely chosen ones. The syndrome was, however, not complete till the name of its purpose-built capital, Islamabad (the city of Islam), was added to it by an otherwise secular military man, the Field Marshal Ayub Khan. The dogma that one has at hand, thus, is not anchored in the land that it was conceived for, but in religio-ideological thin air. In fact, anything tangibly indigenous was anathematised and shunned.

The Pakistani leadership deployed this dogmatic cocktail as the supra-ethnic gel to keep under its heel the diverse ethno-national groups that were included in Pakistan. The ideological state model comprised of an Islamic and pan-Islamic identity, anti-India chauvinism rooted in the ‘martial race’ fantasy and the market economy (virtually implying Western and US aid), was chosen over a nationalist democratic polity. This faux nationalism, which quickly morphed into a rabid hyper-nationalism, was actually an ideological identity that did not have its feet on the ground it ruled.

The state’s propagandists, especially under its military rulers starting right with General Ayub Khan, disseminated this into curricula and society at large. Fantastic notions that one Muslim can overpower (ostensibly with divine help) ten ‘infidels’ made it into the national psyche around this time. Flying in the face of all empirics and common sense, a case was made that the people living in ‘the crucible of Islam’ were somehow superior to the extent that they could not only cut a much larger adversary next doors but also help the West fight the ‘godless’ Soviet Union.

A sense of what elsewhere is the national self-esteem, mutated in Pakistan’s case into what the philosopher, Sam Vankin, calls a collective pathological narcissism, wherein: "the groups as a whole or the members of the group feel grandiose and self-important. They are obsessed with group fantasies of unlimited success, fame, fearsome power or omnipotence, unequalled brilliance, bodily beauty or ideal, everlasting, all-conquering ideals or political theories".

This phenomenon is not unique to Pakistan but has manifested in its most virulent form in ideological states, the prime example being the Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler. This delusion of grandeur falls flat on its face with reality checks, such as defeats in wars. But, instead of an honest introspection, the narcissist groups resort to denial and rationalisation that either such devastating events did not happen or there were causes absent which they would have prevailed against the overwhelming odds. Sometimes a completely fantastic defense is deployed in which the humiliation is erased from the memory and replaced by the narcissist group’s triumph.

The delusions of paranoia and persecution kick in almost in tandem. Like Hitler blamed Jews, Roma, and the communists for every ill befalling the Reich, Pakistan has its set of scapegoats in India, Jews, USA, and Ahmadis. The deceitful narrative is pervasive. Almost every Islamiat and Pakistan Studies book taught today in Pakistan bears this out.

Conspiracy theories have become a national psychological defense mechanism in Pakistan through which the people and the state avert confronting the inconvenient truths. Acknowledging bitter realities would require harsh introspection and potentially remedying things and policies that have brought Pakistan on the verge of implosion.

Guilt and an impending sense of doom are highly anxiety provoking. The Pakistani national psyche seems to have developed a way around these anxieties that demand a tough but desperately needed course correction. Denial, rationalisation, fantasy and the conspiracy theories seem to have become the opium of the Pakistani masses and the elite. Will they be able to wean themselves off in a meaningful manner soon? I wouldn’t hold my breath.