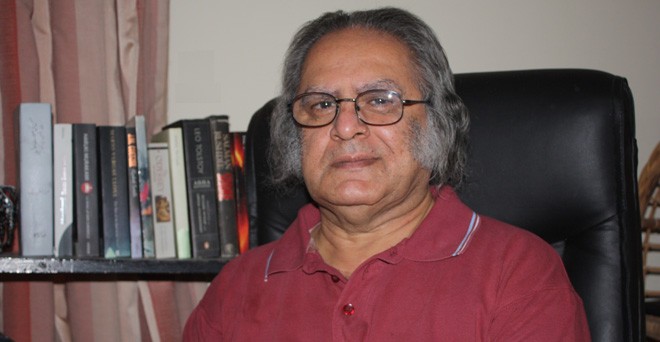

Mirza Athar Baig’s debut novel Ghulam Bagh (2006) is generally considered the first post-modern novel in Urdu. His second novel Sifr Se Aik Tak was an authentic commentary on the state of post-colonial South Asia and was equally appreciated by the highbrow critic and the general reader. The collection of his short stories, Bay-Afsana, appeared three years ago and here he is, with his third novel, titled Hassan Ki Soorat-e-Haal.

Mirza has been a teacher of philosophy for 32 years and retired as the head of philosophy department at GC University, Lahore two years ago. He has also written 15 serials and more than a hundred plays for Pakistan Television (PTV). He is currently working on his fourth novel.

Before I could start the interview with Mirza Athar Baig, he started in a rather sarcastic tone, "So here we are once again, Arif Waqar and Mirza Athar Baig, and a book in between. Tell me one thing, why do you want to interview me. And why do The News on Sunday people always send you for the messy job, knowing fully well that you are a friend of mine and would be critically biased. Could we, for a change, conduct an un-friendly interview this time…or rather a non-interview"?

Thus began this conversation which, in Mirza’s words, is a non-interview.

The News on Sunday: You have used a lot of scriptwriting techniques in your new novel Hassan ki Soorat-e-Haal and whole sections read like a screenplay. Do you think you learnt some of this while writing television plays?

Mirza Athar Baig: Of course I learnt a lot about this type of writing during my television play-writing days. But the presence of almost a whole screenplay in the novel about a fictional surrealist film is an integral part of the narrative. The activities of the film group, bordering on burlesque at times, are intended to mirror the multiple layers of the same events. What is happening in ‘reality’ is sort of rediscovered in the screenplay and vice versa.

As the film group is obsessed with the idea of making a surrealist film, the surrealist ambience in a mock fashion spills over into the main body of the narrative as well, for very well- defined purposes.

TNS: And what are those purposes?

MAB: Well, they are rather ambitious I must confess -- to achieve a creative synthesis of a Soorat-e-Haal (state of affairs) in an almost Wittgenstein sense. Hassan’s state of affairs is the totality of situations denoting our historical, civilizational, creative and cognitive existence. Realist models of novel writing somehow didn’t suit me to achieve my ultimate goal.

TNS: And do you think you have succeeded in achieving this aspired goal.

MAB: Well, total success may only be possible in engineering, not even in science, but never in art and literature. What I can say is that I am pretty much satisfied with my effort, and the readers’ response so far is echoing my feeling.

TNS: You just mentioned Wittgenstein, your mentor and guru in philosophy. It’s a known fact that his ideas were generally misunderstood and distorted even by his close associates and disciples. He had no illusions that his ideas would be better understood in the future, so he fearlessly wrote whatever he wanted to. How do you deal with this dilemma: being truthful to yourself on the one hand and being accessible to the average reader on the other?

MAB: Well, well, well! Talking of gurus and mentors in philosophy I have none. I cannot possibly have one, Wittgenstein or anyone else. I am at the periphery of the philosophical world with no tradition to live by and creatively contribute to. I am an outsider, standing on the edge, trying to watch and enjoy the show. There is a huge gap between the centre and the periphery which I playfully try to fill (laughs). That’s it. Khali Jaghain Pur Kero (fill in the blanks). You see!

TNS: I guess I do. What about the second part of the question?

MBA: If I really decide to be truthful to myself, nothing else matters. Frankly, I don’t believe in this notion of ‘average reader’. I believe every reader is an extraordinary reader and I always get my share of them; not a small number by the way, keeping in view my publisher’s sale report.

TNS: There are some great stories about objects or stories told through objects i.e. megaphone, wine bottle, table etc. What inspired you to do it?

MAB: Yes stories told through objects, is a more appropriate way of putting it. You see humans and object are inextricably linked but when it comes to narration of events, fictional or real, it is the human factor which is in sharp focus. This is understandable in reality but, in my fiction, I have used the biographies or histories of thing to decentralise the human world around them. Thus, I have tried to achieve a perspective and a narrative distance from the human world, giving it a new impartial light and neutrality which is very useful to solve a number of narrative problems.

I have tried to achieve detached syntheses of events through this technique, squeezing long-drawn information or intricate themes into apparently prosaic and unimportant history of a humble object.

TNS: Short story and novel are two different entities. The first chapter of Hassan ki Soorat-e-Haal namely Oochatey Khauf ki Dastan originally appeared as a short story. Now, a novel cannot be an elaborate form of a short story by any stretch of definition. So, how did you manage to develop a short story into a 600 page novel?

MAB: Of course, they are different genres. You are right, the first chapter of this novel was written as an independent short story, published in fact in The Ravi, the literary journal of GCU in 2009. But that doesn’t mean the novel is a stretched out form of the same. In fact while writing that story, I had a strong feeling that the text suggests themes, ideas and a whole gamut of creative possibilities which could be more elaborately explored in an extensive narrative. So, in the actual novel, Oochatay khauf ki dastan becomes a point of reference for a fictional editorial voice doing all sorts of tricks and generating multiple forms of texts all merged into a state of affairs, a soort-e-haal.

TNS: Saeed Kemal, Aneela, Saifi, Safdar Sultan…the whole set of characters, reincarnates in another stretch of space-time continuum. For the Urdu fiction reader, the only precedence of such reappearance of namesakes happened in Quratulain Hyder’s magnum opus in 1957. Were you directly inspired by Aag ka Darya while planning that part of your narrative?

MAB: Aag ka Darya might have inspired me in other ways but not in this literary trope -- of employing the same names for different characters in the same novel. The objective behind this harkat, or gimmick if you like, was to blur the identity spaces of different characters, and to induce a feeling of the instability of self and an uncertainty of the psychological profiles of characters as unfolding in the flux of events.

Also, the intended uncanny feeling contributed to the overall surrealistic but markedly reflexive atmosphere of the novel. Moreover, it was a ‘bundling technique" for me as well.

TNS: And what’s that?

MAB: Forget it. Leave something for the reader as well.

TNS: What do you think means success in novel-writing.

MAB: Well, to begin with, if you are interviewed and your book is somewhat favourably reviewed in the leading English literary supplements -- luckily the Urdu press has forsaken this literary pastime since ages -- you can consider yourself to be a successful novelist (laughs)

The whole experience is quite funny if you look at it threadbare. You write a novel in a couple of years. Finally, the thing is out there in the cruel world of the reader. And then the misery of the writer starts, beginning first of all from his own close circuit of friends aka enemies. That is their moment of exaltation and they have an uncanny awareness of it ("The moron will have to wait", they think). And wait you do. There does come some feedback but generally there is none. People have far more important work to do than reading your lousy novel. But initial silence is a good sign, I may tell you. If expletives are not hurled at you in the first three weeks, you would be spared later on as well. However, if there is some conspiracy of silence against you, better become a part of it.

TNS: The playful way in which you experiment with form in your novels indicates a firm belief that your intended reader is going to follow you. Where does this confidence come from? Is there anything in the tradition of Urdu fiction that supports this confidence? Or do you feel you operate in the space created by modern writers of the West whose works are relatively better known locally?

MAB: Well, I have a strong belief that a writer should create his readers and not himself be created by the readers. If I have anything original to say, or have an illusion of originality, then nothing else matters except being published and be available in print.

Moreover I don’t underestimate the intelligence and literary maturity of my readers. There are a lot of clichés in vogue about what the readers want, which are mostly simplistic and false. My readers have never disappointed me; they love aesthetic and cognitive challenges and intricacies of narratives. Yes, exposure to global literature certainly has influenced the ‘what to expect’ from Urdu novel; definitely so. The tradition has to be local and global; otherwise the novelist would be irrelevant to the contemporary sensibility.

TNS: Parody has been one of the most effective ways of depicting and commenting on our social reality. In your fiction, it seems to take two different forms: your biting sarcasm is reserved for the likes of Salar Network, Kubba Group and Khassi Club, while the compassionate caricatures of, say, members of the Lucky Star theatre, are essentially different. Would you be willing to call it your political standpoint, or did it come off hand, without your conscious knowledge.

MAB: My political stand, if you like, but basically a humanist and moral position. I have a deep-rooted aversion for all forms of pseudo-elitism, because such elitism becomes the glorified handmaiden of the most wretched forms of social oppression. Caricature can go both ways, of course, in rejecting the perpetrators of oppressive dominance and in giving a voice and visibility to the ‘arzal naslain’ -- the humiliated and the lost ones. Members of the Lucky Star Theatre constitute one such lost human world of performing art in our fading cultural history. They were dedicated men and women with an amazing flair for our traditional theatrical lore and which we used to see for whole nights on as youngsters in village fairs and melas.

I am nostalgic about that ecstatic display of theatrical activity, with moments of rapture and frisson, which is no more, and it becomes one of the major narratives in Hassan Ki Sooratee-Haal along with the quixotic film group, of course.

TNS: You were brought up in the liberal atmosphere of an educated middle class family, and the deep structure of our caste-ridden society couldn’t possibly be your first-hand experience. Yet, it is very vividly observed and graphically described in your fiction, particularly the last two novels. Would you like to name a few local writers of the past who may have contributed to your awareness in this regard?

MAB: Well, let me correct you, if you do have to locate me in the traditional social class division, I belonged to something like an upper, lower middle class family. My father being a school teacher and mother as well in a small town in the centre of a rural cluster, we had a lot of "first-hand experience" of the ground level realities of our feudal society, with its inherent dehumanizing caste structure and much more. So I didn’t need to study any local writer for the express purpose of enhancing my awareness on this issue. Many of my school day friends were from doongaypind -- villages situated in the rural outback, and my cherished places for vagabondism and sheer adventure of being a wilful tramp. The experiences are inexhaustible.

TNS: What is the state of fiction in Pakistan? Do you read contemporary stuff? What Urdu books have inspired you?

MAB: Majority of fiction writers still are following the traditional models. They may be great but in my humble opinion the tradition has to be rediscovered in the light of the present. The question of contemporary relevance cannot be ignored. But I have found that writers of a certain age group find it next to impossible to overcome the stiffness of their mental joints. So the greatest haters of my little work are of my age group, a decade plus or minus.

TNS: Many critics or rather commentators have labelled you as Post-modern writer. What would you say?

MAB: Generally, I don’t say much when labelled as ‘post-modern’ because I consider it as a naïve and simplistic categorisation. The ‘modernity’ we have in our parts of the world is a vastly different socio-historical process than western modernity, out of which the so called post-modernity evolved. What sort of ‘post-modernity’ would bloom out of our ‘modernity’? Something is laughable about it but a lot is poignantly serious. There should be a different name for it, and the name is Hassan ki Soorat-e-Haal.

TNS: What had been the most irritating question for you during your various interviews?

MAB: Well, something like…. "Sir there is a lot of philosophy in your novels, is it because you teach philosophy?" It makes me furious.

TNS: One last question. There is a lot of philosophy in your new novel as well, is it…?

MAB: Hold it! This I shall answer off the record. I guess it is time for tea.

This is a revised version of the interview that was published on June 1, 2014.