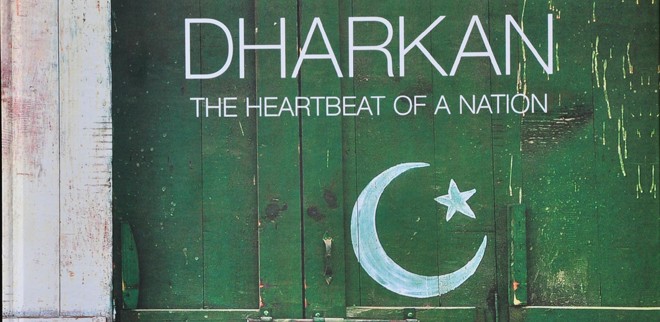

Some of them are household names -- people with whom many of us have grown up and who are part of our shared memory. Others acknowledged as supreme masters in their own fields, have only recently been propelled into public consciousness. The personalities in the book entitled, Dharkan: The Heartbeat of a Nation, however, are only a small part of the extraordinary gifted people the nation boasts. Mobeen Ansari gives the viewer an intimate glimpse -- a fresh insight -- into their minds and spirits.

It was a challenging task for Ansari to portray these distinguished Pakistanis, who have woven their own lives into a story of marvelous character. During his photographic odyssey, many remarkable men and women, who must have inspired him with their artistry and dedication, have enriched Mobeen Ansari’s life.

Portraits of artists distinguish themselves from portraits more generally in that they are born of an encounter between individuals who share a similar defined social role. Dharkan: The Heartbeat of a Nation seeks to consider a recent history of such encounters: Mobeen Ansari’s depictions of his fellow artist friends, peers and idols.

When an artist visually acknowledges a fellow artist, living or dead, there exists not only the recognition of another human being, but also the recognition of a peer. In this sense, artist portraits commemorate and concretise the intimate social dramas of the art world: the private (or privileged) interactions, relationships and ‘economies of exchange’ that typically exist beyond or outside public scrutiny.

Central to experience of works like Ansari’s is the visceral engagement we have, as viewers, with images of other human beings: an experience made explicit in ‘Akram Masih: Sanitation Worker’, Ansari’s animated portrait of the janitor, whose features acknowledge the viewer’s regard.

Ansari’s expressed desire to place his relationship with the labour and the working class on view to a public underscores the social intention and nature of artists’ portraits of other artists. This need to put a face on the world catches the essence of ordinary behaviour in the social context; to do the same in a work of art catches the essence of the human relationship and consolidates it in the portrait through the creation of a visible identity sign by which someone can be known, possibly for ever.

Dharkan, however, uses a picturing system that remains separate from art, that does not seek art’s blessing and that has a different set of aspirations. Its framing of art runs counter to the art world’s celebration of itself as a world apart. It expresses skepticism towards the art world’s certitude that art is and ought to be the terminus point of the imagination, the pinnacle. If Dharkan is a critique of anything, it’s a critique of this certitude.

That something might stand outside art and report on it, comment on it, editorialise about it in an iconic language of its own -- this was, and apparently still is, disorienting. The reason, I submit, is that it instantiates a complication of the modernist dialogue between life and art. Dharkan suggests that a triangulated model whose points are life, art and entertainment -- a competing communication system as madly self-sustaining, self-referential, and self-celebratory as art, has superseded the old binary model. Showbiz adds another category that’s neither art nor life.

The insight that artists are a species of entertainer isn’t especially profound. What makes Dharkan stand out is the fact that work conveying the news is aggressively contemporary in its form and unapologetic in its attitude. Dharkan is made by an affluent urban Pakistani who has watched a lot of television, listened to a great deal of pop music and hadn’t had much exposure to feel for classical culture.

In reducing or erasing the gap between artist and entertainer, Dharkan cheerfully represents another step in Pakistani culture ‘s gradual movement away from its colonial inheritance. To Pakistanis, that earlier cultural model, with its hierarchical ranking of one pleasure over another, has come increasingly to seem at odds with this country’s homegrown culture. Pakistani culture is adamantly horizontal.

A book such as Dharkan merely acknowledges our understanding that no one part of communication culture, no one form of expression, has a lock on truth. A viewer of Friends may derive pleasures from it, which, while different in kind, are just as real and just as satisfying as the pleasures derived by a viewer of the paintings of Gerhard Richter.

Yet, even if we agree with David Robinson’s assertion that the contemporary art world might increasingly be thought of as a kind of intellectual show business and acknowledges the occasional high-profile artist’s appearance in more recent advertising or fashion campaigns -- Ed Ruscha modeling in Gap ads and Tracey Emin’s endorsement of Bombay Sapphire gin come immediately to mind -- the artist remains, even in an age of proliferating media opportunities, a relatively anonymous figure.

While Ansari’s portraits of artists seek, in a modest way, to address this general lack of visibility, images of other creative individuals. Through their role as performers, musicians and actors, trade on their audience’s ability to identify with their unique persona: an identification assisted by the marketing and publicity departments of multinational entertainment conglomerates.

Writers, with whom artists perhaps share more characteristics, frequently appear in highly mannered portraits on their book jackets, where they are invariably presented as serious individuals, worthy of the gravity that their words -- and agents -- demand. However, the identity of artists remains somewhat mysterious. The art world has no equivalent of the dust-jacket portrait, or the million dollar budgets of Hollywood marketing departments. This general lack of visibility continues to perpetrate the mythology of the artist as an outsider: an individual on the shadowy fringes of society.

Ansari’s Dharkan is created partly as an attempt to encounter this romanticised image of the artist. Ansari’s photographs have a rough element to them, which is probably due to his ability to pull confidence and a connection out of a subject. The skin tones are always apparent and people usually have a good sheen on their skin. It’s not all retouched or powdered. He wanted to create a picture of artists that was consistent with his own experience of the world…the men and women of his acquaintance were, and remain, cheerful, generous, pensive and reasonable people. He resents the image of them as mad, romantic-dreamers, hopelessly out of touch with reality.