The world around us seems more religious than ever. Gradually, religious passion has become more visible in our society, which certainly has major policy and security implications for the country. The lack of will and understanding about religious diversity has created space for the extremist narrative. And, this growing trend is not only contributing to religious intolerance but has the potential to deface Pakistan’s multicultural and multi-religious identity.

A visibly upward tendency towards rejection of pluralism and the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach followed by extremist elements can further complicate the relations between Pakistan’s religions. It can eventually push Pakistan into isolation among the comity of nations.

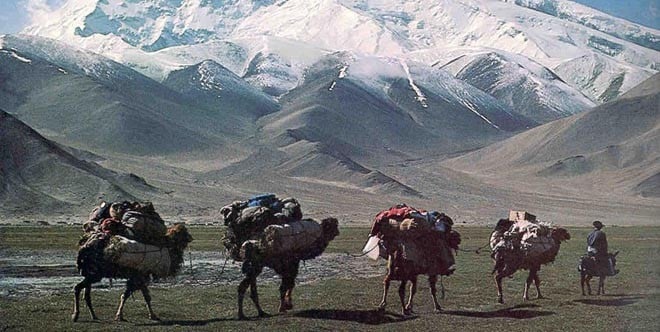

Today’s Pakistan needs peace and harmony between as well as within its diverse religious and spiritual communities much more than ever. The country needs to look back to the celebrated Silk Road to draw some inspiration to revive Pakistan’s ancient and pluralistic identity. For, the Silk Road offers the greatest example of ‘how beliefs and indeed civilizations often reflect a broad pattern of synthesis, rather than clash’. Throughout its existence, the Silk Road played a key role in promoting pluralism by bringing the people of diverse cultures and faiths close together.

The Silk Road was not a single road or a highway that started in Changan (China) and ended in Antioch (Turkey). Basically, it was a system of intertwined paths, tracks and steppe routes that once connected China in the East with Europe in the West. It started in Changan, near today’s Xian in China, from where it extended towards western China. At the mouth of the Tarim basin it was bifurcated into two branches. The first branch passed the northern edge of the Tarim basin and reached Kashgar through Turfan and Aksu.

The other branch followed the southern edge of the Tarim basin and reached Kashgar passing through Khotan and Yarkand. According to the well-known scholar Ahmad Hasan Dani, it was this southern branch of the Silk Road that threw down paths "towards Karakorum region, opening a passage for trade to the Indo-Gangetic plains". These paths originated in Khotan, Qargalik or Yarkand from where they followed several passages to reach the present Chitral, Hunza and Gilgit.

Dani has identified two routes leading to Hunza, Gilgit, Chitral and Chilas from the Chinese towns. The first route crossed the Muztagh River and passed through Shimshal to reach the main channel of Hunza River. The second branch extended towards the present Tashkurgan, the border town between China and Pakistan. From here it either travelled towards Wakhan or towards Khunjrab.

The famous Chinese pilgrims Fa-hian and Song-yun, according to Dani, took the Tashkurgan route to reach Gilgit. Another celebrated scholar Karl Jettmar through his lifelong research on rock inscriptions and engravings in Gilgit-Baltistan, has also identified a number of passes and ancient routes in the region that connected Pakistan with the Silk Road system. He maintains that the Kushan rulers of Gandhara used the route through the Karakorum as a strategic link to the oases on the southern fringe of the Tarim basin and the preachers of Buddhism used the same tracks on the way to the Far East.

Caravans of the Silk Road carried not only silk as leading luxury, but also non-material things such as language, religion, art, technology, manners, and customs to lands far and wide. Asia, the biggest continent and the birthplace of world’s great religions, owes much to Silk Road for the spread of religions and for pouring pluralistic influences and values to the major parts of Asia. By far, Silk Road’s greatest contribution to human civilization is bringing diverse cultures and religions together.

To this day, many places along the Silk Road stand witness to the influence of world’s great religions such as Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Manichaeism, Sikhism and Zoroastrianism.

Arteries of the Silk Road passing through northern Pakistan helped Buddhism to become a world religion. From the subcontinent it spread to Afghanistan, Central Asia, China, and Far East following routes of the Silk Road system.

The Kushan rulers’ policy of religious tolerance towards all religions helped the spread of Buddhism to the lands afar. Kushan King Kanishka-II not only patronised building of Buddhist monasteries and stupas in the kingdom but also supported rewriting of the Buddhist texts in Sanskrit. Of the eighteen major Buddhist schools, Mahasangikas, Sarvastivadins, Dharmaguptakas, Tantric and Mahayana schools had all their presence along the Silk Road between the first century BC and the fifth century AD. The greatest success of Buddhism was its spread into China following the Silk Road. There is evidence to show that in the first millennium AD, Buddhists built hundreds of cave temples, brought in scriptures, and established religious libraries around Dunhuang in China.

Christianity, like other religions, followed the trade routes and expanded along the Silk Road towns in Turkey, Iran, subcontinent, and as far as China. Antioch in Turkey, the western most terminus of overland Silk Road, became an important center of early Christianity. A group of the Eastern Christians, who followed Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople, influenced the highly talented Sogdians who were the inhabitants of fertile valleys in today’s Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. During the first millennium AD, Sogdians were the great traders and ‘the main go-betweens of exchanges’ along the Silk Road. Together with trade, they also became the transmitters of Christianity further east into China. The Nestorian school of Christianity was highly successful in mass conversion of Turks in Central Asia from the seventh to the eleventh century AD.

Arab trade missions established connections with China within a few years after the passing of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) who himself was a travelling merchant before becoming the last Prophet of God. Following largely the existing trade routes, the Arabs later conquered the lands as far as Transoxiana in Central Asia in the eighth century AD. The propagation of Islam in Central Asia owes much to scholars, merchants and most importantly Sufi mystics who spread the faith by example. Sufis such as Ahmad Yasawi and Bahauddin Naqshband played a key role in building Muslim communities in Central Asia.

Historical evidence shows that Judaism reached China during the reign of Chou dynasty in 1100-221 BC. The Jewish settlements in China appear to have been founded by traders coming from the west. Studies inform that after the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BC, the Israelites were forced to relocate into other lands including Central Asia. Many of the Jewish settlers of Central Asia were engaged in long distance overland trade. Apart from the exiled Jews in Samarkand and Bukhara, Judaism once had many followers in today’s Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan and India.

Manichaeism named after its founder Mani was once the most widespread religion of the world. Basically, the Manichaean belief drew influence from contemporary religious traditions including Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism and Christianity. Under the official patronage of the Sassanid Empire of Persia, Manichaeism spread throughout the Mediterranean, West Asia and Central Asia. In Central Asia, the religion attracted Sogdian merchants and Turkish nomads who transmitted Manichaeism further along the Silk Road into China. Translation of Manichaean texts into Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian, Uighur and Chinese was a major factor for the success of Manichaeism along the Silk Road.

Zoroastrianism as one of the earliest religions of the ancient world was once widely practiced along the Silk Road. Since its beginning somewhere between Mongolia and Azerbaijan around the thirteenth century BC, Zoroastrianism spread across the greater Iran, including Mesopotamia, Caucasus, Khwarizm, Transoxiana, Bactria and the Pamirs. The religion spread eastward to China and the subcontinent by the eighth century AD. Its founder Zoroaster sought to reform the prevalent pantheism to monotheism and taught belief in Ahura Mazda or the Lord of Wisdom.

Hinduism and Sikhism are also among the major creeds of the Silk Road and both were founded in the subcontinent. Following its spread in South Asia, it was Silk Road’s maritime routes that helped Hinduism to spread as far as the Malayan lands.

Sikhism, at one point, exercised its influence from its place of birth in Pakistan to the borders of Afghanistan and China. It is clear from historical evidence that for centuries devotees of world’s major religions have lived together along the Silk Road and particularly in the areas forming the present Pakistan.

We cannot let religious intolerance creeping into our society prevail over the once most pluralistic region of the world. Located on the crossroads of Asia, Pakistan can play a major role in reviving the spirit of the Silk Road and connecting cultures! A revived spirit of pluralism and a revived Silk Road are key to Pakistan’s future.