(part 2)

Our meetings of leisurely conversations were less frequent now. Previously we had chatted about life and literature and actors and the London Theatre. He was fond of holding forth. Chatting is not the right word. He held forth. I was mostly a silent listener. I would offer an opinion now and then, but he remained much too absorbed in whatever he was saying to register it. But I am grateful to him for telling me hilarious stories about Robert Atkins and Wilfred Lawson.

After Sian’s arrival the scene changed. Sian would now invite me to join them at lunch or dinner. It was interesting to note that Peter, who spoke and behaved like an upper-middle class chap, turned into a devil-may-care, flamboyant Irishman in her presence. Whether it was an act he put on for me, or whether he wanted to send up the sophisticated etiquette of Sian, I don’t know. Sian was an actress of no mean standing, but whenever there was talk of a play or a performance, she would offer her opinion guardedly as though she was unsure that what she was saying would meet with Peter’s approval.

We were walking on the sea-front one night. The sea was calm, Apropos of nothing she declaimed, "Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage, before the dying of the light." She spoke the lines beautifully, but then she stopped. "You do it Peter, she said, "You do it so much better…. go on darling" she coaxed Peter. He spoke the poem as Irish blarney. I was in fits. Sian laughed as much as was befitting. She seemed to want to live up to his expectations at every moment. There was something slightly odd about their relationship. It was too well stage-managed. I wasn’t surprised when I learned, some years later, that they had parted.

The debonair French movie-star, Maurice Ronet, landed in Akaba. He had been cast to play Prince Ali in the movie. Ronet spoke English with the kind of French accent every stand-up comic in London loved to do in his act. David Lean was a bit perturbed about it. He asked me and Peter to spend some time with him in the evenings. "See if you can straighten out his speech a bit," he said.

Scripts in hand, we used to go over his lines in all the scenes in which Prince Ali appeared. Ronet tried, and he tried hard, but could not manage to "straighten out his speech"

Peter got a bit bored with the sessions. He often left me to go through the script with the French star. Maurice Ronet was a highly personable chap, but he was unable to shed his "Bebe…" mannerism.

And so, after a few days when Lean asked us how Ronet was getting on, Peter said, "Ask Zia, he has been conducting most of the lessons. I think he’s a bit poncy." Maurice Ronet was heart-broken when he learned (not from Lean but from the producer, Sam Spiegel) that he was going to be eased out of the movie.

After weeks of restful life of Akaba, we were moved to an unmapped part of the desert where a tented village had been erected to accommodate the now enlarged unit of the film company. The temperature, in shade, was never under 42 degrees, centigrade.

The nights in the desert were wonderful. It felt lovely to sit and lie on the velvet soft, cool sand, but the first rays of the sun were like pincers piercing the skin. Working from eight in the morning until sunset, or just before, in the gruelling sun, can be tiresome for anyone, but we worked in the open with the ‘brutes’ (five kw lights) focused on our faces. It was nothing short of severe hardship. My skin acquired the colour of dark brown chocolate.

After three weeks of this ordeal Peter and I were sent to Amman to ‘rest and recuperate’ for two days in Amman. Saturated in dust, we arrived at the hotel after a ten hour drive and agreed to meet in the lobby after a long leisurely bath.

Peter did not turn up. I never saw him during that break. I was taken back to the location after three days all by myself. Peter was already there. When I approached him he sang ‘Not a word, not a word, not a word, not a word’. It was rumoured in hush-hush tones that he was ensconced in a secret place with Sam Spiegel’s very attractive secretary.

I shall never forget the first day of shooting which began in the afternoon. ‘Action’ said David Lean. Peter and I riding our camels approach the mark where we had to stop. Peter takes a gulp from his canteen and then offers it to me. I don’t take it. He insists that I do, and I say something like "I am a Bedouin I don’t need it." "Cut," shouted Lean. He was obviously not satisfied. "Let’s do it again," he said tersely. There were seventeen if not nineteen takes. Peter was sweating and so was I. After the first two or three takes Lean didn’t give us any specific directions. "Let’s try it once more" he would say. And we went on until we heard him say. "Alright chaps, that’s a wrap."

When I went to say Good-bye to David Lean after I had finished my work in the desert, I found him quite relaxed. His face was less stern now. He asked me to sit down. "I think you’d like your work when your see it on the screen," he said with his winsome smile.

"May I ask you something?" He nodded.

"What was it that I was doing wrong on the first day of the shoot? Please tell me now".

"Oh," he chuckled. "It was a bit of a joke. I wanted Peter to realise that filming is going to be a bitch of a nightmare. I just wanted to knock the wind out of his sails."

* * * * *

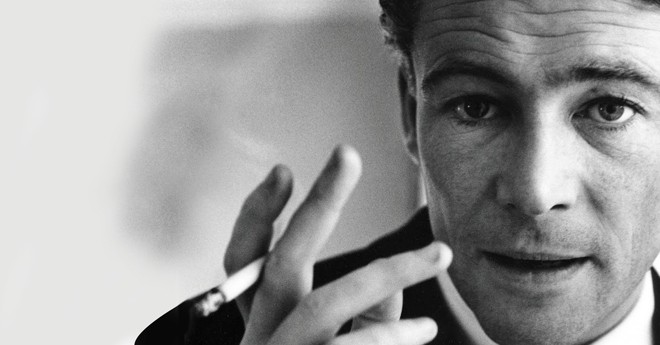

The impression of Peter O’Toole that I took back to London was that he was a man totally absorbed in himself, a highly self-centred person. Later on I changed my view. Peter was ambitious, more ambitious than any other actor I had ever come across. His was the kind of ambition that brooks no obstacles. He wanted to pluck the stars and put them in his pocket. He wanted to own the world and that is not a bad thing for a young actor to desire.

Peter O’Toole wanted to dazzle not only the stage but the screen as well -- and he did.

Concluded

Read the first part here