We all have our set of hang-ups, anxieties, moments or objects of rigidity, fixations and preoccupations. There are things of which we may be intensely mindful, taking care to do them in a certain way or at a certain time. Sometimes, the effort we put in to organise things, to get them just right, the way we want them, to avoid anxiety, is functional -- such as a pathologist working in a lab ensuring that blood samples are not mixed up, an editor checking references, a surgeon performing a complicated procedure, a parent checking on a toddler to see if s/he is safe, or someone checking the gas and locks before going away.

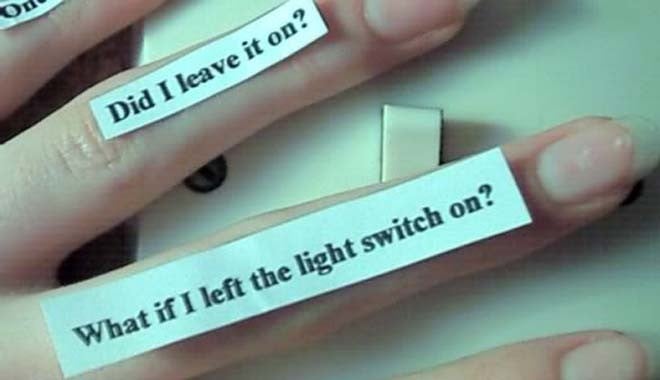

Some form of order, structure and routines are all desirable features in our life -- because they make difficult work easier, more manageable and more efficient. But what if this order, routine and anxiety, makes your life more complicated, exhausting or even painful? When your anxiety or any particular thought becomes almost constant, when it consumes, when you perpetually worry about it even though you have done what needed to be done, when you feel the need to do something over and over… and over… and over again because otherwise your mind won’t be at ease, when you know it is excessive and irrational, you still worry about and give in to the pressure to do it.

And when the anxiety or behaviour that follows in your day-to-day life and begins to affect your personal wellbeing, health, work and/or relationships, it is time to think about Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Recurring thoughts (obsessions) about something that is worrying (for example, what if I didn’t check the locks properly when I left and someone breaks in?) and the need to carry out a certain action or series of repetitive actions (compulsions) in order to alleviate that particular anxiety (for example, checking the locks over and over again) are the key features of OCD, although obsessions are not always accompanied by compulsions. Rigid structures and rituals often become a part of the routine of a person suffering from OCD because they help provide order, certainty and, consequently, some measure of mental relief. But this relief is temporary, lasting only until the next episode, which in many cases is just around the corner.

As a result, a large part of many sufferers’ lives is spent worrying and doing things to prevent or reduce that worry. Understandably, this leaves little time, energy and mental space for the demands of everyday life, in extreme cases, debilitating its victims and significantly damaging her relationships.

Take Saima (not her real name), a 32 year old woman, married and mother to three children. Saima was pressurised by her husband of 11 years to see me in therapy because he felt her condition was ruining their family relationships and social life. From the moment Saima walked into the clinic, she was clearly uncomfortable and cautious. She looked around uneasily, assessing, as I guessed, the level of cleanliness in the room. She did not seem satisfied (OCD sufferers with obsessions around cleanliness seldom are), but she sat down with her husband, and we began to talk.

Saima had always been very "particular" about cleanliness, especially around her clothes and space for namaaz. Over the years, this had become so serious that she no longer ever left home, never visited anyone, not even her own mother, because she felt no place was ever "clean enough". If there was an urgent need to do so, all pieces of her outside clothes were separated from her inside clothes, they were kept and washed separately, and never allowed to come into contact with each other.

Elaborate systems had been established for when her husband and children returned home from work and school, their clothes and shoes put into plastic bags at the door step and whisked away to a separate washing area. They were to immediately go in for baths, but without touching anything on the way, not even the bathroom door knob, lest it become contaminated with germs from the outside. Saima would be ready and waiting when they returned to complete these rituals and ensure there was no mistake. If there was, excessive cleaning followed, sometimes taking hours at a time. All dishes, utensils, clothes and even food was washed so vigorously, often with heavy detergents, that Saima’s hands and knuckles bled, and were peeling when I saw them. The children’s school bags were washed every day and their books kept in a separate room; after their homework, they were to wash their hands a certain number of times with hot water and soap before they could enter the rest of the house.

The children knew that something was wrong, and were beginning to show signs of their own set of anxieties and aggression. The husband felt that if things didn’t improve soon he would have to take the children and separate.

Not all sufferers of OCD have such extreme regimes. The example above illustrates the degree of anxiety and the enormous efforts made to reduce it that are part of lives of many people with OCD.

A preoccupation with germs and the need for cleanliness is a common obsession. Others are constant safety concerns and unwanted, disturbing, and what the sufferers consider ‘inappropriate’ thoughts about religious, sexual and moral issues -- for example, profanities or sexual fantasies coming to mind while praying or thoughts of hurting one’s children, even though there is no such inclination. Irrational meaning association with people, objects, places, colours, etc., are also common obsessions.

A key feature of the disorder is that these thoughts are intrusive -- the more the person tries to actively avoid them the more they are likely to enter his mind.

Common compulsions that may follow obsessive thoughts are hoarding, counting, arranging things in a certain pattern, washing/cleaning, repeating certain words/phrases after a certain act and having rituals around how certain things are done. For example, certain things may be touched a specific number of times before they are used, only a particular route must be taken to walk into another room, etc.

OCD is related to chemical and functional abnormalities in the brain and may be genetic. It may also be caused by the environmental factors, such as growing up with someone with OCD. Stressful life events may also render a person vulnerable to OCD because of the relief that order, structure, certainty and stability may bring in an otherwise chaotic life that does not seem to be in his or her control.

People with OCD are typically aware of the irrationality of their behaviour, and their lives may be significantly impaired by the thoughts and rituals that dominate them. However, shame, embarrassment, and at times the effort and rituals required to step out of their safety zone and seek professional help, prevent many from getting the treatment they need. But help is available, involving therapy or medication (in many cases both) and can significantly reduce, or even eliminate symptoms, allowing sufferers to lead meaningful and happy lives.