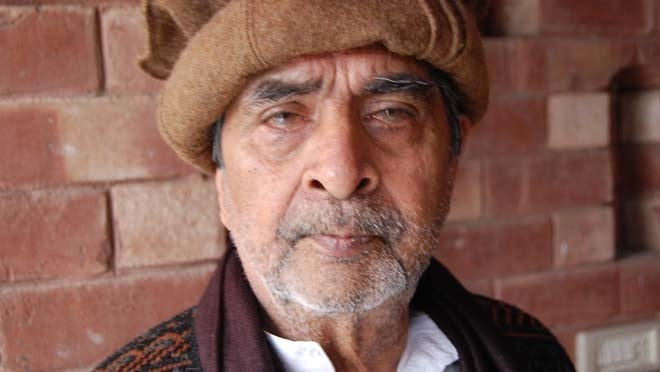

Jamaluddin Naqvi (known as Jamal Naqvi) joined the Karachi group of Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) in the mid 1950s, assumed all important posts in the party, and later ran his own faction of the party like a sole rider till late 1980s when he left the CPP on ideological grounds.

His autobiographical account has been published recently under the title Leaving the Left Behind, which is self-explanatory. If someone wants to know more, he can read the subtitle "An autobiographical tale of political disillusionment that took the life’s momentum away from the myopic politics of the Right and the Left to the enlightened concept of Right and Wrong".

In a scenario where there is no archival record of the left, either in the form of official statements/documents or memoirs (Dada Amir Haider Khan’s biography being an exception), how can one evaluate our common progressive past politics? This is where the value of this book lies. Jamal has not made any disclosures or revelations in the book. Those who have met him during the last decade or so know this well. Like a bold and courageous political worker, he didn’t hide his change of heart.

When prominent Indian Bengali communist Mohit Sen penned his autobiographical account A Traveller and the Road: A Journey of an Indian Communist [2003], he too faced outright condemnation from the CPI rank and file; yet his book is considered a pioneering effort in unfolding the myth of the Indian left.

Unfortunately, there is a narrow space for rethinking or revisiting the past politics and ideologies among the South Asian left which is said to be dogmatic. We love to live in a black and white world; there is no room for gray areas especially for those who want to move away from their previous ideological positions. When someone changes his position, we treat him as a zandiq (heretic). So Jamal is another zandiq among reds.

Ironically, Jamal gave his whole life and career to progressive thoughts and spent many years in prison but when he amended his thoughts, he was discarded. These memoirs are the only way to revisit the past and to analyse the history of the left movement in Pakistan.

It was with this understanding that in 2003, I along with the help of some old friends like Kalib Ali Sheikh, Pervaiz Majeed and Qaisar Nazir Khawar published 33 interviews of various South Asian left leaders -- irrespective of their groups -- in the journal Awami Jamhoori Forum. It is a useful resource to understand the diverse points of view of Pakistani, Indian and Bangladeshi left.

Jamal was born in Allahabad in 1933 into a well-educated family. His grandfather Syed Zaheeruddin was a lawyer while his father Syed Nihal Uddin was a lecturer in Allahabad University. Among his seven brothers and sisters, three went on to attain doctorate degrees. Jamal’s father died in 1944 when he was in his forties. His brave mother decided to take the Munshi Fazil exam for which she had to come to Lahore. That courage runs in Jamal too.

Jamal’s first interaction with the left came at the end of World War II through his cousin Shafiq Naqvi (1946) who was then a role model for him. Shafiq was an office bearer of the Communist Party of India (CPI), UP chapter. At that time, the CPI was supporting the demand for Pakistan.

He came to Pakistan in 1949 and did his graduation from Islamia College Karachi and got a chance to listen to lectures of M.H. Askari, Mustafa Zaidi and Professor Karrar Hussain. Here he joined DSF which was formed in late 1948 at Lahore, a fact often denied by some of the left circles in the past. DSF Karachi was formed after the Lahore and Rawalpindi chapters, in 1950 at Dow Medical College. However, among the names mentioned Jamal has missed the significant name of Eric Rahim of Lyallpur who along with Hassan Nisar (maternal grandson of Nawab Mohsin Ul Mulk) played an important role in establishing DSF in Karachi.

In a lecture at Awami Jamhoori Forum, Jamal had accepted that his spiritual guide in progressive politics was Sobho Gyan Chandani while his guru in practical politics was Eric Rahim. In his long interview in Awami Jamhoori Forum, Eric had recorded many names who attended the cell meetings in early 1950s in Karachi including Dr M Sarwar, Nasim Ahmad, Yousaf Ali, Ayub Mirza, Saghir Ahmed, Barkat Alam, Mir Rehman Ali Hashmi, Haroon Ahmad, M. Shafique, Adeeb Rizvi, and Hassan Ahmad. Jamal Naqvi and Imam Ali Nazish joined the party at a later stage.

According to the book, when the CPP was banned in 1954 Mian Iftikharuddin of Punjab had formed the Azad Pakistan Party. Actually the Azad Pakistan Party was founded in 1949 at Lahore.

In 1956 A.B.A Haleem, then vice chancellor of Karachi University, declared Jamal Naqvi as an "undesirable element" depriving him of the chance to get a job in Karachi. At this stage, Mirza Abid Abbas, husband of Mrs Naqvi’s sister who had a private college in Hyderabad, Sindh, rescued him. Mirza Abid’s sons -- Athar Abbas (Major General and former director ISPR), Mazhar Abbas, Zafar Abbas, Azhar Abbas (all journalists) and Anwar Abbas -- were tutored and trained by Jamaluddin Naqvi.

In his book Jamal has criticised Mir Thebo, Imtiaz Alam and Shamim Ashraf Malik. He says that Major Ishaq had also joined CPP in late 1970s which was never the case. He was a leader of Mazdoor Kisan Party.

The left movement in South Asia was a scattered formation right from the beginning (1930s) and it remained scattered in Pakistan too. But Jamal Naqvi fails to analyse that phenomenon. He has written about the expulsion of personalities like Comrade Tufail Abbas, Minhaj Barna and Hussain Naqi from the CPP in its formative years -- late 1950s and early 1960s -- but fails to evaluate the impact of such mistakes even in 2014.

There are many more gaps and omissions in the narrative not only regarding the early days of the left movement but also regarding inner part struggle & other communist formations. But he does record many significant events which make the book exceptional. The dedication reflects Jamal’s age-old love: "Dedicated to the rather idealistic but cherished dream of a global democratic and equitable dispensation".

With nine chapters and two appendices in this 264 page volume, the 81 year old Jamal Naqvi has shared all that he had to with his comrades. You may not agree with him but it is important to acknowledge this wise effort. We hope our elders in the movement would follow his example and give us a chance to read more about our common past.