A symposium at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) last week paid tribute to the late Pakistani architect and activist, Perween Rehman, and highlighted the universality of issues faced by the urban poor worldwide.

The event, titled "The Orangi Pilot Project and Legacy of Architect Perween Rehman," paid tribute to the late architect and OPP director as "a woman, architect, and social activist." They also discussed parallels between the issues faced by the urban poor in Karachi and elsewhere.

Hosted by the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the event was spearheaded by graduate students Fizzah Sajjad and Hala B. Malik from Lahore.

Academics from India, Pakistan, and the United States presented papers and participated in discussions. Prominent among them were Akbar Zaidi, Kamran Ali Asdar, James Wescoat, Anita M. Weiss, Laura A. Ring, Anita Spirn, and Miloon Kothari, former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing who is currently at MIT.

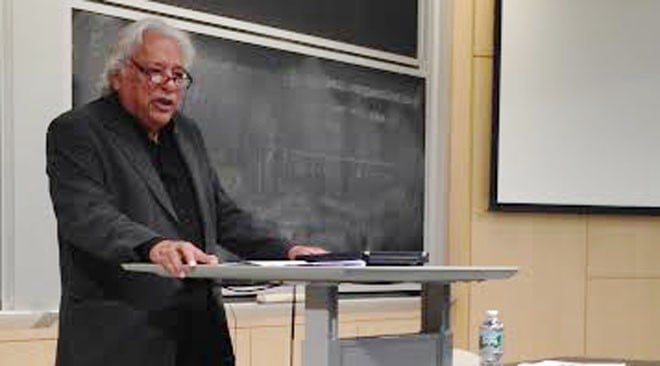

Ironically, Perween herself had decided long ago to not attend such events, reflected architect Arif Hasan, Chairperson of OPP and Urban Resource Centre (URC). His keynote speech, outlining Perween’s life and work, kicked off the day-and-a-half long event.

Graduating in 1982 from the Daud College of Engineering and Technology in Karachi, Perween was among the first batch of students Arif Hasan taught.

The following year, fed up with doing projects for the rich, she came to work with the legendary Dr Akhtar Hameed Khan at the Orangi Pilot Project he had started in 1980.

Perween learnt on the job. She supervised the mapping and surveying of Orangi, carried out by students not much younger than her. This cost a fraction of the amount that an international agency was charging.

Some years later, she initiated the OPP-RTI (Research and Training Institute), which manages projects like low-cost sanitation, secure housing support, education, water supply, and women’s savings, and training programmes. One of its greatest contributions has been mapping and documenting numerous settlements in Karachi.

Over 70 per cent of katchi abadis in Karachi are now regularised, thanks largely to the advocacy work of Perween Rehman and the OPP.

Her greatest achievement, reflected Arif Hasan, was to make OPP "a people’s project", and to "bring people closer together". She refused to deal with the ‘big’ bureaucrats, preferring to focus on those working at that ground level. That in itself was a major shift in how advocacy was done. It led to changes in the laws, and changed perceptions towards informal settlements.

"Laws are important", as Arif Hasan put it, pointing out that it took 11 years to frame the Katchi Abadis Act, and this, in turn, became part of the Karachi Development Plan.

There is a strong anti-poor bias, not just in Karachi and Pakistan but all over South Asia, and indeed, the world, observed Balakrishnan Rajagopal, Associate Professor of Law and Development and founding Director of the Program on Human Rights and Justice at MIT.

Around the world, the poor are being pushed into smaller settlements, he said in his thought-provoking talk on various kinds of violence, including those that are structural and institutional, weighed against the poor.

Transport is geared towards the much-touted vision of the ‘world class city’, rather than connecting the poor. Indeed, slogans like "world class" or "slum-free city" are "dangerous ideologies that sanction violence on the vulnerable at the policy level".

Re-locating people to make room for ‘development projects’ causes an increase in poverty levels as incomes decrease. Children pay a heavy price as their schooling is interrupted.

Meanwhile, as literacy levels are rising, people are becoming more aware of their political rights. Ironically, the more assertive they become, the more conflict is generated -- the police tend to be heavy-handed when it comes to dealing with protests by the poor.

Another common phenomenon, from Mexico and Brazil to South Asia, is the personal risk taken by those who work with the poor. The violence against defenders of equities, rights and the poor needs to be explicitly recognised, suggested Balakrishnan.

Over-commercialisation and commodification are giving rise to a certain kind of consumerism, and the consolidation of a trans-nationalist capitalist class. Exploitation of natural resources pushes rural dwellers to the cities, where they are forced into slums, making them vulnerable to disease and other issues related to urban poverty.

Arif Hasan has suggested that architects and town-planners develop a code of ethics and take oath like doctors do, to refuse projects that displace the poor or are environmentally or ecologically unfriendly. Given the neo-liberal agenda that is being pushed globally, the suggestion is unlikely to receive a sympathetic hearing among his colleagues. But it is certainly something worth pushing for.