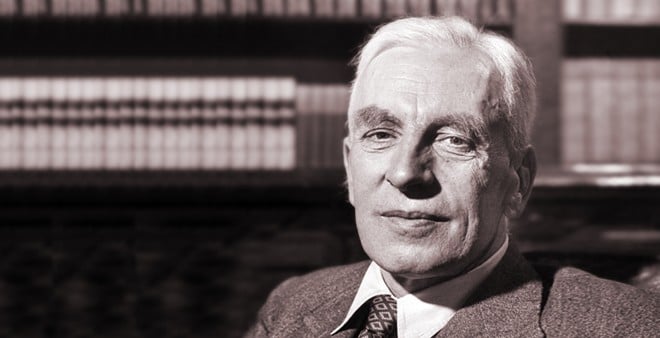

In March 1947, Arnold J. Toynbee appeared on the cover of Time magazine that hailed him as the most provocative historian since Karl Marx. In 1952, he delivered the prestigious Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh which were later published as An Historian’s Approach to Religion. The last volume of his magisterial and monumental book, A Study of History, analysing the rise and fall of civilisations in 12 volumes, appeared in 1961.

Although his influence waned after mid-1960s, Toynbee was the most celeberated historian of the last century. In 1955, he wrote an article titled, Pakistan as an Historian sees her, which was included in a collection of essays published as Crescent and Green -- A Miscellany of Writings on Pakistan. This impressive anthology of essays, based on 16 pieces by noted Pakistani and foreign writers, was published by Cassell & Company in London.

Toynbee’s perceptive, precise and, in some ways, prescient essay, is worth reading even after nearly 60 years -- as it clearly shows the path we should have followed but did not. His analysis and advice on issues such as the role of religion, sectarianism, race and language, treatment of minorities, relations with our neighbours, overpopulation etc. is still as relevant today as it was then.

Toynbee noted at the start that Pakistan is "a child of the strife that has arisen from the impact of Islam upon Hinduism". Although it had been nearly a thousand years since Islam established itself in Indian subcontinent, Toynbee rationalised the creation of new state when he wrote "the pace of the psyche’s self-adjustment is so slow that, in A.D. 1947, the Muslim community in the Indian sub-continent decided that there was still not enough common ground" between the two communities, Muslims and Hindus, to remain united under a single government, given that the former British Indian Empire was to become independent and self-governing.

Discussing the interplay of religion, race and language, Toynbee observed that what Pakistan stands for is the "transcending of physical and linguistic differences by a common religion". He warned in his article that if, in Pakistan, "political allegiances were to be decided on lines of race or language, Pakistan would immediately fall to pieces."

Just 16 years after the publication of this article, his warning turned out to be prescient -- as Pakistan broke up in 1971 due to the reasons outlined in his essay.

Further explaining the role of religion and risks associated with it, Toynbee made a statement which is perhaps at the crux of the crisis that the country is facing more than five decades later: "A common adherence to Islam is manifestly a force that binds a majority of the people of Pakistan together; but now I am going to venture onto more controversial ground. I should say that it would be a calamity if Pakistan were ever to become a Muslim state in an exclusive and intolerant way, for then Islam might become a far more disruptive force than the racial and linguistic differences which Islam at present overrides."

Toynbee also analysed the potential problem of sectarianism that Pakistan has been facing for the last few decades. He pointed out that Pakistani Islam is not unitary as "the Shi’ah and the Ahmadiyah, as well as the Sunnah, are represented in it".

Given this diversity, Pakistan, Toynbee opined, could never be identified, as is possible in the case of some countries, with some particular Islamic sect. He brought up the issue of various and numerous minorities living in the then two wings of Pakistan and emphasised the need for living together as fellow citizens, expressing hope that if they succeed in achieving this, they will be rendering "pioneer spiritual work, not only for themselves but for the world as well."

It is quite obvious that Toynbee would have been disappointed by today’s Pakistan and the trajectory it has followed in the last 60 years.

Toynbee’s essay was written just a couple of years after the first anti-Ahmadi riots in 1953. Since then, Ahmadis have been declared non-Muslims and, in the last decade, Shia killings have claimed thousands of innocent lives due to the menace of sectarianism that Toynbee had cautioned against. Violence against Shias and persecution of minorities such as Ahmadis, Hindus and Christians in a country created on the premise of safeguarding the rights of minorities of the Indian subcontinent is a blot on the country’s raison d’être as a separate homeland for minorities.

Toynbee rightly pointed towards the danger of ‘Sunnisation’ in a diverse country like Pakistan. Recently this disturbing trend of ‘Sunnisation’ has been accompanied by another confusing drift towards ‘Arabisation’, which displays our identity crisis as well as ignorance, if not outright denial, of our Indo-Persian culture and heritage.

‘Arabisation’ refers to the growing tendency of using Arabic words instead of Persian (such as Allah Hafiz instead of Khuda Hafiz or Ramadhan Kareem instead of Ramazan Mubarak etc), increasing number of hijab-wearing women and the vocal rise of Wahabis marginalising the Beralvi majority. Gulf money, in form of remittances, charity and funding of religious madrasahs, has accentuated these twin trends of ‘Sunnisation’ and ‘Arabisation’.

Arnold Toynbee in his magnum opus A Study of History as well as his travelogue Between Oxus and Jumna, based on his travels through Afghanistan, Pakistan and Northern India in 1960, mentioned that the subcontinent belonged to the Persian zone of cultural influence rather than the Arabic one. Although Islam had been brought to Sindh and Multan by the Arabs in the 8th century, it was only in the 12th century, after the Turkish rulers’ consolidation of their rule over north India, that one can state that Islam was established in the Indian subcontinent.

Persian emerged as the language of the court and administration under the Mughals who embraced Persian culture and civilisation.

In his article, Toynbee discussed the perils of overpopulation in both East and West Pakistan and entertained high hopes for Karachi’s future as a thriving seaport servicing the landlocked areas of Pakistan. He also threw light on the border dispute between Afghanistan and Pakistan but stressed in unequivocal terms the need for good relations between Pakistan and its neighbours specially India, "Moreover, Pakistan cannot live without good relations, not only between her own citizens, but between herself and her neighbours. While there is a Hindu and a Sikh minority in Pakistan, there is also a Muslim minority in the Indian Union… these minorities across the frontier should be, not hostages, but ambassadors and interpreters, helping Pakistan and the Indian Union to live as good neighbours. Pakistan and the Indian Union are tied to one another by unalterable facts of geography".

Although Pakistan’s relations with Afghanistan and India have been tense since inception, Pakistan enjoyed extremely warm and close relations with Iran during the first three decades -- as Iran became the first country to recognise Pakistan in 1947, Pakistan’s air-force jets, despite protests by the Indian government to the Iranian monarch, landed in Iran during 1965 and 1971 wars to avoid harm from the attacking Indian jets. It is the senseless pursuit of elusive strategic depth in Afghanistan since the 1980s and the recent presence of jihadi outfits in Balochistan, accused of launching attacks on Iranian soil, that have made our relations with Iran prickly.

Looking at the situation today, Pakistan, instead of achieving strategic depth, suffers from strategic shrinkage with loss of territory in Fata to Taliban who have set up base there to launch attacks with impunity on Pakistani cities, and then retreat back to recuperate in Afghanistan.

The irony is that Pakistan enjoyed strategic depth (when our airforce jets landed in Iran during the two wars) and has lost it due to our flawed foreign policy. And the tragedy is that Pakistan has been trying to find this strategic depth without success, and at a terrible domestic cost, in the crags and canyons of Afghanistan.