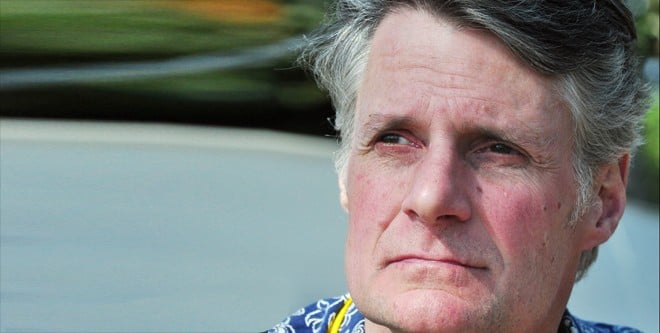

Good looks, comic brilliance, and career success have not prevented Marc Parent from doing what he does best: living life as an emotional basket case. More riddled with pain than an arthritic joint, Parent is to publishing what Edvard Munch was to painting -- the ultimate scream.

Marc Parent has been working in international publishing for 28 years in the wake of his studies in French and Comparative Literatures at L’Ecole Superieure Normale and at the College de France in Nanterre and Paris, and at ColumbiaUniversity, NYC. For the last 10 years, he has been a publisher of foreign fiction and non-fiction at Editions Buchet/Castel in France, where he put together a major Indian and Pakistani catalogue of writers, including Daniyal Mueenuddin and Padmasambhava’s Tibetan Book of the Dead.

In May 2013, he started one-of-a-kind literary agency, IndiaMaya Literary in Paris representing writers from all around the globe, with a special focus on fiction and non-fiction writers from India and Pakistan.

His publishing behind him, Parent holed up in Beach Luxury Hotel in Karachi on the occasion of KLF 2014 summing up his motives for the work as an effort to use thoughts about undoing the buttons of the ego to gorge out a proposition of his own.

Before his retreat,TNS tracked him down on the lawns facing the creek for an update. Unassuming and frail, he was nonetheless exuberant. Excerpts follow:

The News on Sunday: What does it mean to be a literary agent in France? What kind of a role does a literary agent play in the literary world?

Marc Parent: I have been an international publisher for over twenty-eight years and a literary agent for not even over a year. Even though I live in France, I don’t consider myself part of the French publishing world -- the market there is already dominated by publishers as opposed to the Anglo-Saxon world where agents dominate the market and to Poland where it’s the distributors. In France, the relationship between the author and the publisher is bilateral which excludes the agent. In other words, authors don’t have agents in France because the publishers claim to be their agents. Having said that, publishers often exploit the authors making it rare for the authors to live off their writings on their own.

According to my agenda, I represent authors, especially those from the Indian subcontinent, who I edit and promote worldwide, and not just in France; I represent these authors in the same way as I publish them by being very close to their work and by acting as an editorial advisor, a counsellor, an editor, and by taking their work to different markets.

TNS: What has been the focus of your research while studying comparative literatures in France?

MP: Because of my background -- my father was American, my mother French -- I was raised in both English and French languages, which, somehow, made me different from my colleagues who were a bunch of Francophiles. I was raised in a rather cosmopolitan environment, which is why it was only logical for me to choose foreign literature in addition to French. My initial interest took me to Romantic literature -- to Germany, Italy, France and England. Gradually, I was drawn to what is now called The Lost Generation. In other words, to the American expatriate writers living in Paris, between 1917 and 1945.

I did my Masters focusing in on publishing of magazines and books by the Americans in Paris between 1920 and 1940. The writers who I approached from this era were Ernest Hemingway, F Scott Fitzgerald, Harry Crosby, John dos Passos, etc., in addition to James Joyce from Ireland, Marinetti from Italy, and Franz Kafka from Czechoslovakia. Their writings were being compiled into Anglo-American magazines active between the two Wars. It was a very rich period that saw the birth of the Dada, Futurism, Cubism, Suprematism, Surrealism, and so forth -- the ism itself being a mark of history. This was my laboratory!

TNS: How did the introduction to South Asian literature come about?

MP: My connection with South Asian literature, specifically India, came through my grandmother. She was half-French and half-Czech, born in Paris to a French-speaking mother and a German-speaking father. (Czech, in those days, meant part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). She emigrated to New York when she was merely 17. While there, she discovered the works of Swami Vivekananda who’d come to Chicago in 1893 as part of a huge conference on religions during which he introduced Hinduism to America.

My grandmother arrived in the United States twenty-five years later when Swamiji had begun constructing Shri Ram Krishna Ashram in NYC. In a rather karmic twist of fate, she started to work for this ashram, and spent the next seventy years of her life as its die-hard devotee, first in New York and then outside Paris in the 1950s. She had a child -- my mother -- born in NYC. When she would come to visit us on Thursday afternoons (when we didn’t have a class), there were two things she would always carry in her bag: prasada and a copy of Bhagavad Gita.

When I went to India for the first time at the age of twenty, I felt I was entering a familiar terrain. When I started to publish Indian authors, I began by going into the history of the subcontinent. Meanwhile, I have published five Pakistani authors and ten-fifteen Indian ones. The catalogue that I managed to put together is a recognised and coherent document dedicated to India and Pakistan. There is a message that I’ve tried to pass on to the French that in terms of literature, there is no partition, and that both Indian and Pakistani literatures stem from the same extremely powerful tradition of storytelling that has remained alive for more than 5000 years.

TNS: Which Indian authors initially led your way into the world of publishing?

MP: Because I was attracted to India from the bottom of my heart, and to Hinduism, and to life in cities and villages, I was trying to look for writers writing against the flesh, certainly not the Diaspora. It all started with a novel I discovered in 2004 called The Alchemy of Desire by Tarun J Tejpal, which I translated into French in 2005 as L’ouen de Chandigarh (Far from Chandigarh). I thought it was an incredible piece of fiction that haunted me for days on end. When I published it in 2005 to critical acclaim, all 300,000 copies of it were sold in France alone. It created a real stir in the country because the sales outnumbered Amitav Ghosh, Vikram Seth and even Salman Rushdie. I have always tried to pursue that vein of writers who are close to the flesh of India. When I continued reading and publishing, I proceeded on with non-fiction by Gurcharan Das, Suketu Mehta, Pankaj Mishra and Rajmohan Gandhi. I have published fiction by Aravind Adiga, Kiran Nagarkar, Tushani Doshi, Jaspreet Singh, etc. This spate was followed by Pakistani writers such as Saadat Hasan Manto who I regard as the maestro, directly from Urdu into French.

TNS: Earlier on, you said that in your opinion, Partition could not divide the literary traditions of the subcontinent. What is your opinion of literature spawned by Partition itself and its aftermath, beginning with Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan down to Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children?

MP: When I say that, it’s in comparison to our tradition of storytelling that was broken up after the Second World War. Yours has never been interrupted but ours broke up and gave birth to the kind of literature that brought the French novel into slow decline. It was the kind of novel borne of guilt of the elite at having had its hands bloodied in the roundup of 76,000 Jews and sent out to Auschwitz with the approval of the French authorities and intellectuals. It kept them from continuing to tell stories because they were not able to find courage in themselves to admit that by telling stories they cannot hide the facts, even though they were not fully involved in the horror but were accomplices.

After WWII and the birth of nouveau roman on the French cultural scene, the arrival of semiotics, the fascination with French literary theory a la Roland Bathes, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, the writers were not writing stories that enchanted us anymore. After WWII, the big storytelling a la francaise that started in the 19th century with Flaubert and Stendhal, and continued with Aragon, was over. (I was a part of it because I followed Barthes’ classes for two years at the College de France. I still remember Barthes saying: The novel I want to find one day on my table has to be a novel that corresponds to three concepts. A perfect novel has to be simple, readable, and filial to the language it’s written in. All the writers would go home and write in line to what the master had said). The sad demise of French fiction in the world (and how it is hardly translated anymore) says a lot about the power of literary theory on fiction rendering it unreadable.

As of the 1950s and the 1960s, the French readership turned towards American literature. It was the Golden Age of American fiction, and the French were reading John Updike, Norman Mailer and Ernest Hemingway. In the 1970s, they drifted to South American literature, to Marquez et al and to Afrikaner literature. They were ready for Indian storytelling after that. I was able to convince them that 5000 years ago, two very important texts were written: The Mahabharata and The Ramayana; that these ‘novels’ gave birth to a tradition of storytelling in India that young Indian writers still follow today.

TNS: There are three kinds of literary traditions in Pakistan: literature in the native tongue; literature written in English by authors living in Pakistan; and finally, English literature of the Pakistani Diaspora. How do you see this multi-faceted tradition?

MP: The distinctions you have underlined meet mine in a certain way when I say I am more interested in literature that comes from the flesh of India as opposed to the literature of the Diaspora. I am very well aware that there is much more to the literature coming out of India in English, and the same applies to Pakistan. The distinctions that you’ve drawn are absolutely valid but appear to be a bit too sophisticated for the audience outside Pakistan. The point is what is our perception of Pakistan in the West. It’s a hard country full of drones, explosions, earthquakes, the Sharia in the North, killings and corruption, the ISI and the Mullahs. For people outside Pakistan, it’s a complex mosaic.

These writers make me understand Pakistan, and the language they employ is English. But is it really the English language we are used to hearing in the Anglo-Saxon world? It is more of a South Asian concoction, and that is exactly what makes it so fascinating. How else can you contain in a word, let alone a novel, the complexity I was talking about -- the mayhem, the contradictions, the conflicts, and the idiosyncrasies? Could the Englishman’s English be enough to contain the violence and noise of the people of India and Pakistan? It needed to be amended and reinvented. It had to be patched up with Bengali, Malayalam, Pushto and Punjabi (to name but few), to translate the soul of this region.

TNS: What sets the literature from Pakistan apart from literature coming out of India? Is there a measure of comparison?

MP: India has not completely exhausted herself but has come to a moment of respite, resignation, and perhaps comfort. Ever since I was born, I have believed that literature (mainly fiction) is what will help explain the world to me, and I have always looked for answers in literature. Talking about India and Pakistan, one is faced with the two most complex countries in the world, and this complexity is not necessarily born out of Partition.

At the same time, I believe that Partition is a scar that has not yet healed, bringing with it a major part of complications both countries are going through today, whether it’s Kashmir or Mumbai, discrimination or the Gujarat riots -- almost everything has the tendency of coming out of Partition. The way literature has been able to absorb Partition and explain it to readers like me, gives me the feeling that India has, more or less, settled its score with the issues surrounding it. And since there is more serenity in India concerning her relationship with herself and with the world, the Indian writers are no longer writing for the West; they are not there to explain themselves anymore; that India is a country of saris, spices and henna that underlines the picturesque in a country.

TNS: There’s been a plethora of literary fiction in English by the Indian writers published in haste by Penguin Viking, Harper Collins, Rupa, India Ink and Yoda Press, etc. Is there a policy at work that determines, discerns or qualifies a manuscript from getting published or is it a laissez faire situation?

MP: The role of the publishing houses is very important. Penguin India started out some twenty years ago while Cambridge and Oxford have been here for about a hundred years. Their presence and that of other Anglo-American publishers in India speaks for a commercial interest and potential, that is, the English language market in India is estimated at three hundred million people. Of course, this has attracted commercial opportunities to tap their way into the Indian market, publishing houses had been looking for, whether they’re academic or otherwise.

The publishing world in the West is in such disarray today -- publishers are in dire straits; bookshops are gradually dying; readership is dwindling. I think, respect should be accorded to those who arrived here twenty-five years ago and have delved into the Indian market to survive and to look for a turnover and opportunities by achieving what they couldn’t back home. Publishers are professionals with two major qualities: the flair, the intuition, the aptitude, and secondly, a sense of marketing.