Why has the history of film gained so much attention lately? This question actually falls in the realm of cultural anthropology. A layman’s guesswork will tell you it is a game of nostalgia. We still are a nation of cine-goers but no longer a country of film-makers -- a country that used to produce 120 movies a year.

The local film production has come to a standstill. But we can proudly look at our glorious past -- when Lahore and Peshawar nurtured great actors like Prithviraj, Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand and Pran, when six film studios were working day and night in Lahore churning out movies for cinemas all over South Asia, when as many as 22 film journals were published from the cultural hub, including Cinema, Star, Movies, Screen World, Film Pictorial, Movie Flash, Movie Critic, Cine Herald, Chitra, Paaras, and Khayyam.

Parvez Rahi, the veteran film journalist from Lahore, had carefully preserved the files of these film magazines from 1930s to 1940 and, on the basis of this archival treasure compiled a book, titled Punjab Ki Filmi Tareekh. The book recently went into a second edition.

Another such person who devoted a lifetime collecting information about Pakistani movies was Yaseen Gureja. He compiled a Pakistan Film Directory in 1967 which contained detailed information about each and every movie produced in the country. The Directory had addresses, phone numbers and other relevant details about the film producers, directors, musicians, poets, singers, actors and technicians. The book was periodically updated, and after Gureja’s death in 2005, Tufail Akhtar, another veteran of film journalism, took over the project.

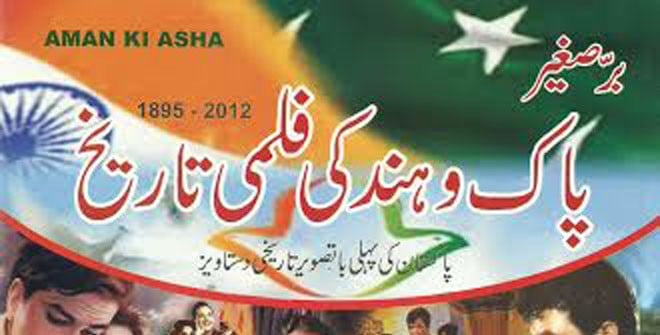

The book under review, Pak-o-Hind Ki Filmi Tareekh came out in 2013, being cinema’s centenary year. Author Iqbal Rahi has been in the field of film journalism for the last 40 years and has compiled biographies of several film personalities including Mustafa Qureshi, Habib, Sultan Rahi and Bahaar Begum.

Like most film histories, the book begins with the 19th century technical experiments in pursuit of capturing physical movement photographically. The author goes beyond the Edison era, and also tells us about the efforts made much before Lumière brothers in France came up with a perfect device for recording action on celluloid strips.

The book is dedicated to Dada Saheb Phalke, the father of Indian cinema, who in 1913 made the first ever motion picture in the subcontinent. Raja Harish Chandra was the title of the movie and all female characters were acted out by young boys, as no women were available for this "strange job".

Books on the history of Indian movies usually start with Raja Harish Chandra, which no doubt, was the first regular movie to be shown in a hall, to the ticket-paying audience. Amateur film-making, however, had been in fashion for quite some time. Iqbal Rahi has painstakingly collected archival material from the pre-Phalke years (1901 to 1912) and much labour has been exerted in digging out stills from these obscure movies. These rare black and white images are the highlight of this section.

Before moving on to the first "talking picture" of India, Iqbal Rahi takes us to the Hollywood of the mid-1920s, where Warner Brothers, after the earlier experiments of synchronised sound in 1925, had come up with a fully fledged "talking and singing picture" in 1927. It was the famous Jazz Singer, generally considered to be the first talkie of the world.

It is rather sad to note the author has comfortably skipped the most interesting part of this development when, in England, Germany and Russia, the great masters of silent cinema were sceptical about the advent of sound, and feared that all achievements of the silent montage, gained through hard labour of 20 years, will be washed away by this cheap mechanical gimmick of sound.

Anyway, within three years of its introduction in the US and Europe, the technique of synchronised sound reached India, and Ardeshir Irani, the famous Indian filmmaker, got credit for producing the first Indian talkie called Alam Ara (1931).

The next section covers the period of 1931 to 1948 in which all major movies of the era are described, and then, in a sub-section, the development of Lahore film industry (1924 to 1948) is covered in detail.

The book also discusses the traditions of historical and Muslim cultural genres of Indian cinema and there are full chapters on film music, famous singers, super heroes, and leading ladies of our screen.

One notes, rather regretfully, that in the later half of the book, which covers more recent history, the author has depended more on hearsay and anecdotes, rather than serious research. For example, in connection with Sohrab Modi’s magnum opus Pukar, Iqbal Rahi writes, "the role of Mangal Singh was first offered to Dilip Kumar, but he refused it…" The fact is that Dilip Kumar did not exist in the film industry at that time. At the age of 16, Yousuf Khan was just a high school student in Peshawar, and had no idea about his future as Dilip Kumar.

Some of the incidents described in the book are an integral part of the Bollywood mythology, and the general reader likes to believe them. This anecdotal approach may enhance the entertainment level of the book, but it is no help to a serious student of film history. The author may like to edit out all such stuff in the next edition.