My Dad was born on September 7, 1965 in the home of his then lower-middle-class family in the heart of Sargodha, literally during an airstrike on the city.

With an absentee father and five other siblings, his mother bestowed upon the 7-year-old eldest son the duty to run errands -- such as hauling an empty gas cylinder around on his bike to be refilled for home use. Since then, he had taken it upon himself to take care of those around him.

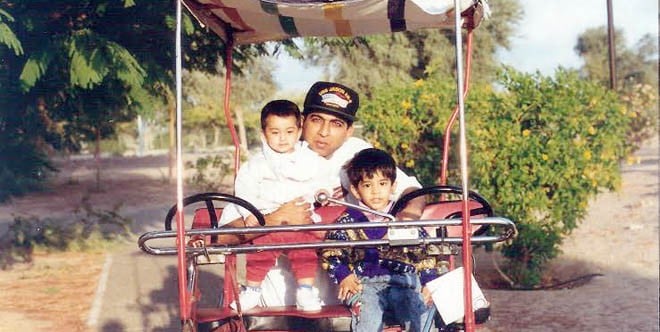

My Dad didn’t have cupboards filled with toys and clothes from around the world that my brother and I had while growing up. Instead he played street cricket every day till sunset, all the while wearing hand-me-downs. If you knew my father, you would know that owning expensive material possessions was not high on his list of priorities. From his phone to his car to his wardrobe, he did not care if it was what everyone else had or not. Despite this, he still worked hard to provide everything my brother and I could ever want and more. Probably the most selfless human being I have had the pleasure of knowing, my Dad only ever wanted to make his loved ones happy.

I received the news by our family friend Jimmy Uncle that my father was in critical condition in the ICU after suffering a heart attack. He told my brother and I not to worry, explaining that my Mom really wanted us to fly back home just to be with her. So, the next morning, we left our respective universities in Canada to return to Pakistan. Deep down I suspected something worse than what was told to us and so couldn’t help but shed tears as we flew across the world.

It wasn’t until our layover in Doha when I was browsing Facebook that I saw the three letters, which when separated with a period make a devastating abbreviation. Someone had written "r.i.p" on my Dad’s wall.

When we finally got home, my Mom who was desperately trying to keep herself composed in front of her children explained that she had lied to us. There wasn’t a heart attack, there was a car accident. He wasn’t in the ICU; he was in the morgue. He had died before even reaching the hospital, before seeing his children graduate university, and before growing old with his wife.

In retrospect I understand completely why she lied. As a mother it is her natural instinct to want to protect us; she was protecting us from the harsh reality for as long as she could -- that we would never again be able to watch him smoke his pipe, or hear one of his lame jokes, or see him get excited over Pakistan bowling out India.

Walking into his study for the first time after his death made my heart sink. I could still see him sitting at his desk typing away at his keyboard, wearing a red sweatshirt he turned his head towards me and smiled as he always would when I entered. I looked around this frequently visited room which all of a sudden appeared so unfamiliar without him in it. On his desk were father’s day cards from me and my brother, upon a shelf there were transparent glass vases filled with used lighters, an interesting collection which was always admired by his visitors.

Over the next few days, I began to look through his study in more detail. I found a box of old cards and letters dating back to his youth. Among them were many cards from the spring of my parent’s relationship -- cards from my Mom wishing my Dad good luck in his exams, Eid greetings and those from later years expressing her love for him. He had saved them all. In another box there were miscellaneous pieces of paper and photographs, one of them was a parking map of my brother’s residence building from when my dad went to drop him off to university. Another was a picture of my father and Alam Channa, and one with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan from when he worked with Gulf News in Dubai.

Everything in that room must have an extreme amount of sentimental value simply because these involved his multiple moves across multiple continents.

In another shelf were piles of used notebooks that my Dad had saved over the years. It seemed as if he had written down every thought he had ever had. Some were more worn out than others, with dog-eared pages and tea stains, while others were recent such as the one with his flight details from when he visited us in Canada just a few months ago.

In them all however were his thoughts, famous quotes, short poems he wrote, notes from work, interviews he conducted and little drawings. Flipping through the pages of his life, I realised this was a man who still had so much to offer to the world. Maybe I never fully appreciated this fact before because to me he was never Masud Alam; author, poet, journalist, he was Dad; bed time story-teller, shower-singer, cricket enthusiast. I did know however that he was a man who loved to be creative, and had always encouraged education, especially studying the arts. He had an adventurous soul and a lively persona which is what kept him young, an attribute I would always try and emulate.

Growing up he had told me about the indescribable thrill of going bungee jumping from when he was in his mid-20s. So when I was given the opportunity to go myself, my first thought was how I wanted to do it because he did it. He almost didn’t believe that I actually did it and was proud of me for doing so. I can only hope that he is watching over me, and that everything I do from now on in my life will make him proud too.

I love you My Dad, and although I think you left this earth too soon, I am so grateful for the 20 amazing years you were my teacher and friend. There is still so much I wanted to learn from you but, like you always said, everything happens for a reason.

The writer’s father wrote a weekly column titled Yeh Woh for The News on Sunday.