The News on Sunday: How do you look at the varying narratives of the Balochistan-Pakistan relationship at this point in history? Some people think these are laden with confusion, for example between LeJ vs Hazaras, the Baloch vs the Pashtuns, between the pro-federation and anti-federation elements among the nationalists. How do you explain this complexity?

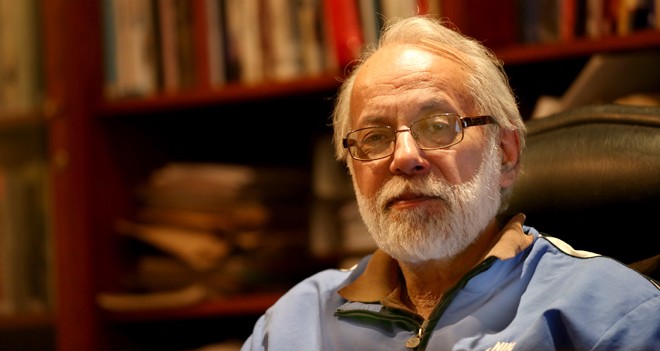

Rashed Rahman: Of course, it’s a complex situation. But, I think, also, people’s knowledge in terms of background and history tends to be limited about Balochistan. And, therefore, it’s sometimes difficult for the people to put things in proper perspective. There is a nationalist insurgency going on. This is the sixth insurgency in the last sixty six years. Even though there were problems from the very beginning about Balochistan’s accession to Pakistan, we have not heard or seen as explicit a demand for separation or independence in previous insurgencies as we have this time. I think this is a reflection of the impatience now and the anger that has accumulated over sixty six years and produced this extreme response.

In Balochistan, when the 1970s’ insurgency ended in 1977, the wisdom that informed the political class in Balochistan was the philosophy of Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo (late). He argued that armed struggle and guerilla warfare was not the way to achieve Balochistan’s rights and the only possible way was to engage with the system, take part in parliamentary elections, and try to win rights through democratic process. They tried that for twenty five years -- from 1977 to 2002. In those twenty five years, although they also formed governments from time to time, including Akhtar Mengal’s government but those governments were not allowed to function the way they were. In fact, Akhtar Mengal was removed. Secondly, even when they had their own people or nationalists in government, they were not able to achieve what Bizenjo may have hoped for.

So, there was frustration, irritation, anger. Balochistan is, of course, a federating unit but its population is so small that in terms of representation in the National Assembly and in the corridors of power in Islamabad, it doesn’t have the same weight as other provinces have. So, their voice is weak and muted. And the Senate, we know, doesn’t have the same powers as the National Assembly. This frustration led the new generation of young nationalists once more despair of the parliamentary process and take up arms again.

The difference between this and previous insurgencies, particularly the 1970s’ one, is that today nationalism is of a far narrower creed, almost exclusively ethnic-based. It is hostile to all other ethnicities, particularly Punjabis because, in their view, Punjab is the actual dominant province in the federation.

The other aspect is terrorism, particularly sectarian terrorism. Lashkar-e-Jhangvi is an extreme sectarian organisation, anti-Shia, and because of its Wahabi theology, it believes shias are ‘wajibul qatl’ because they are ‘kafirs’. A perfectly peaceful and harmless Hazara community became the target of LeJ. Not because the Shia community or the Hazara community were doing anything that could invite such targeting but it is the theology of groups like the LeJ that has persuaded them to kill and carry out bombings that we saw and the kind of attacks on Shia pilgrims -- going to or returning from Iran. These have been massacres, nothing short.

There are other issues but they are not as sharp or conflict-ridden at the moment as these two.

TNS: Some people justify military operation because of the nationalists’ attacks on Punjabi settlers while the sypmathisers of the Baloch cause see the latter as a reaction to the former. Do you see this anti-Punjab sentiment as a continuity of policy in Balochistan or is that a new policy?

RR: It is a continuity of sentiments. The state of Pakistan that came into being in 1947 tended to be, like any other post-colonial state, where the state structure is heavily tilted in favour of the military and the bureaucracy, these being the two things that we inherited. And because democracy was very weak and unable to stand on its feet for a variety of reasons, that opened up space for the military and bureaucracy.

Since the military and the bureaucracy is overwhelmingly Punjabi, therefore, the finger is pointed at them. It is understandable from this point of view and the point of view of demography. But when they say Punjab and Punjabis, the narrow nationalists tend to mix up the Punjabi establishment with the people of Punjab. And this is not being fair for the simple reason that the people of Punjab are not empowered. So, an ordinary Punjabi has no say, even little knowledge, of whatever is going in Balochistan. So, pointing a finger at them is perhaps not justified.

Similarly, the settlers in Balochistan were being targeted some time ago. It was a narrow nationalist response and an unjust act because, a) the ordinary people like barbers, teachers, and labourers were being targeted. It didn’t make sense. What role do they have in the power structure? b) There are two kinds of settlers -- people who have gone there recently for economic reasons and those who have been there for generations. The latter are very much integrated in the Baloch society and support Balochistan, not necessarily for separation but for their rights. Though I support the Baloch otherwise, I have written and argued against this. In my opinion, that was actually damaging their cause, arousing anger in Punjab against the Baloch. In the long run, it is to the advantage of the Baloch people if they have a sympathetic ear in Punjab amongst the people.

TNS: Do you think the Baloch marchers will be able to draw attention to the broader issue of missing persons and the related issues of the PPO and mass graves?

RR: This is a great tragedy. Pakistan has historically been a security state and our security agencies are in the habit of functioning with impunity. Until recently, no one even asked them what they were up to, no one even dared. It is the 2009 restoration of judiciary and its increasing independence under former chief justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry that brought this whole issue to the fore. Of course, he could not go very far but the effort must be lauded in the interest of law, justice, constitution, human, legal, and civil rights.

Where people disappear and their bodies are dumped all over the province and, now in Karachi, badly tortured, badly mutilated, is appalling. No civilised state can possibly allow this thing to go on. Nevertheless, there has not been a greater awareness of the missing persons. They say the number of missing persons runs into thousands, perhaps 18000. The official record shows only a few hundred. And even they have not been produced. So it is a very tragic situation.

Having despaired of sittings and strikes in Quetta, these hardly a band of activists decided to do a long march from Quetta to Islamabad, via Karachi. They got a very good reception on the way in Balochistan and in Karachi and Sindh as well. But I’m sorry to say they didn’t get as good a response in Punjab. In Lahore, it was good to some extent but not to the extent it should have been.

Nevertheless, it is an epic march. And these are not just men, these are women and children, too. So, if that doesn’t melt hearts and if that doesn’t produce for them the desire to provide justice and the desire to disclosure about their loved ones, I don’t know what will.

TNS: As a journalist sitting in Punjab, how do you look at the media coverage of what’s happening in Balochistan. Who is responsible for ensuring the media access and safety?

RR: Frankly, Balochistan does not receive its due in the media. I understand as a media person, the competition and the focus of media as there is so much happening in the country, particularly terrorism. But as a responsible journalist, we cannot shut our eyes to a problem which potentially strikes at the very roots of the federation. Are we fulfilling our responsibility is a big question. The picture is a mixed one.

I remember when I took over Daily Times almost four and a half years ago, there was hardly a mention of Balochistan, either in the paper or on TV. I would like to think that I have contributed something by bringing the issue to the fore by reporting on it, commenting on it, highlighting it and then, slowly and gradually, we began to see change in the media -- both in the print and TV. They have now started focusing on Balochistan. But it goes up and down. If a major event takes place, of course, the media is there. But in between an event, it either tends to be ignored or relegated to an obscure page of the newspaper.

Security forces do not allow the media to operate freely in Balochistan. Forget the interior, which is difficult to access due to logistics, even in Quetta they are not allowed to function freely. Papers have been shut down. Editors and owners have been killed. It is a very dangerous place for the media. The national or the local media is not able to highlight the issue in the manner that they deserve.

When the earthquake hit Awaran you suddenly saw the media descending on it. But how long did it last? And the follow-up is not there. I know more about his because I have friends there and they keep telling me. By and large, neither the media nor the people know what happened to the people after the earthquake.

TNS: The prime minister has hinted at making new roads in the province, seeing development projects as a solution to Balochistan. Is that the correct approach?

RR: It is not a new approach. It was started in the 1970s by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. His argument at that time was that Sardars had a vested interest. They didn’t want development because that would loosen their control over their tribes. But the facts on the ground were the opposite. At that time, there were about a hundred and four sardars. Four of them were in the nationalist movement while a hundred were in the government. And this is the pattern that has persisted.

Even today, if you look at the Balochistan Assembly and the government which is led by the National Party, and composed of PML-N, PkMAP, and others, you see the proportion of sardars in the assembly and in the government is very high. So, if there is an impediment in the shape of sardars it is because the federal government has always tried to utilise them by bribery, power, wealth, or by whatever means. So, the whole approach that by economically developing Balochistan all other problems will go away is like ostrich hiding its head in the sand.

Since the 1970s, all the development projects in Balochistan had a counter-insurgency aspect to them. If you are going to use the roads that you built to run tanks and troops on, rather than for trade and economic development, it is obviously not going to convince the local people. If you were to bring about a political settlement within the framework of Pakistan, it should make the Baloch stakeholders and the state given the province its due, then you do development and it would be welcomed. Nobody wants to live in isolation, poverty, and backwardness in this time and age. I think, unfortunately, poverty in Balochistan is still driven by the security establishment.

TNS: What are the possible solutions to the Balochistan crisis? In the backdrop of Mengal’s six points to the holding of elections and the induction of Dr Malik as the chief minister, is there still a possibility to engage with Pakistani state?

RR: We can’t turn the clock back. What we can do is look to the future. But to look to the future I think we should shed our biases and think broadly. And in "we" I include the military, the political class and so on so forth throughout Pakistan, not just Punjab. First and foremost, accept the Baloch as an equal federating unit and accept the Baloch people as equal citizens of Pakistan.

Their longstanding complaints that they are deprived of their natural resources, for instance gas -- they didn’t have gas till 1985 while we had it in 1952 -- and the royalty issue, should be addressed objectively and fairly. If you do to the GwadarPort what you did with Saindak and Reko Diq, bringing in people from the outside, you cannot achieve the results. If the people of Balochistan are unskilled, set up a training programme and provide skills to the local people.

The most important issue is the political settlement with the insurgents so that you persuade them that staying with Pakistan and coming out from the mountains and participating in an equitable development in which the Baloch will have the fair stake is better than fighting, which in today’s world is not so easy.

Read also: Baloch discontent by Mir Mohammad Ali Talpur