Financially independent writers are a recent phenomenon in world history. As a group, their independence is the result of the way the printing press and modern transportation have changed the world. Before the arrival of the printing press, a writer had to be dependent on the patronage of a king, a feudal lord, a fief, or a monastic or sufi order. Because there was no way of selling books to the masses directly, the writer had no product to sell and, therefore, no way of sustaining themselves financially without having a direct access to stipends or donated money.

The modern writer is a self-employed person with a product to sell because of certain revolutionary and democratising changes. As it happens as a result of every major social transformation, people prefer to fall back on what has always been the most familiar to them. In the case of South Asia, the realisation among the Muslims that they had lost the public sphere to the British produced an urgent desire to galvanise the domestic sphere.

This led to the popular appeal of domesticity rituals and the first true bestseller, especially for South Asian Muslims, was written as Bahishti Zewar. This makes Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanawi as the first true bestselling author with a mass-market that still prevails in some segments. Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanawi’s treatise is a compendium of instructions for women and a diatribe against biddah (innovation). The irony is that the author was relying on an innovation (the printing press) to preach against innovation (biddah). No wonder, Ahmed Raza Khan, the founder of the Barelvi movement, declared Thanawi a kafir.

Eventually, the mass market of the faithful readers had to be divided between many bestselling authors.

After a century and a half, the market and the printing press are both alive and prosperous and many multinationals are clamouring for the piece of the pie.

The number of English speakers in South Asia is greater than the number of English speakers in England. According to one estimate, only India and Pakistan have 214 million speakers. The total population of the UK is 63.23 million and not all of them have English as their mother tongue. The South Asian market is huge and readers of all castes, faiths, and ideologies are willing to part with their rupees to get hold of a quality book. This is the reason behind the fact that almost all mass-market publishers of the English-speaking world have their offices in South Asia.

But in the current era, the scenario is very interesting for any student of culture and history. Originally, English literature was introduced in South Asia to produce "a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect." And the native learners of English were told they could never reach the sublimity and profundity inherent in the Englishness of English literature and, therefore, were traditionally awarded inferior grades.

That tradition was kept alive by the annual system of examinations. We needed American neo-colonialism in our academia to get some modifications in the inferiorising legacies of British colonialism. Calibans not only started producing literature in the language of the coloniser but also started talking among themselves and forgot about the centre. Third world literature has its own global circulation in the same way as technological products of China. Nobody cares whether England has any purchasing power or not.

We are just coming out of our American-sponsored proxy wars and are supposed to enter the right side of history. Wahabism has served its purpose in helping with the disintegration of the Soviet Union. The global culture industry is in search of stories that portray the liberalism and market economy as emancipatory forces.

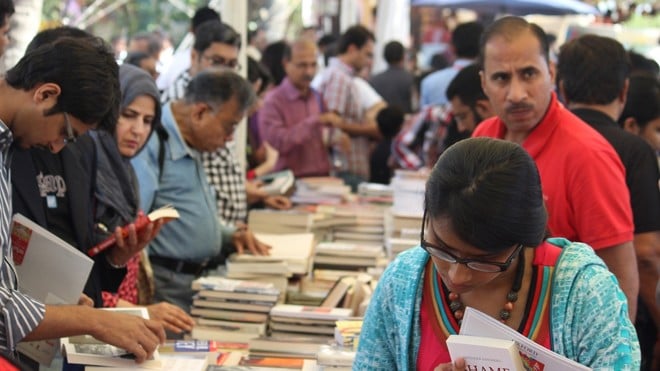

This is how it feels in Pakistan: festivals of literature, which is mostly produced in or translated into English, sponsored by multinational mercenary interests are becoming part of the global celebration of the end of history. The organic festivals, spontaneous eruptions of festivity, organised by local communities on the death anniversaries of popular writers are not getting the attention they deserve.

Does anyone celebrate the gathering of writers and singers and stoners that takes place on the death anniversary of Saghir Siddiqui in Miani Sahib? Whatever happened to the original Faiz Aman Mela is also a story of ignominy. The Sharif brothers and the Jamaatiyas seem to have appropriated Habib Jalib. And the marginally popular character like the reluctant fundamentalist is becoming our global representative stereotype. This is how the local history of resistance and critique will be erased.

If these literary festivals bring Nawaz (the Punjabi short story writer who only used one name) back to the limelight and help us recognise the Borgesian dimensions of Sagheer Malal’s writings, they may prove useful for the local/national literary scene. If Sara Shugufta is only known because Amrita Pritam compiled a book on her, it means the global marketability is determining our literary landscape.

The safest works of literature are going to be celebrated. The non-Western Marquis de Sades are not wanted unless they celebrate the amorphous neoliberal vacuities. The fate of Reinaldo Arenas is for everybody to see. The only book that made him globally known is a posthumous autobiography, Before Night Falls, and that too because it was first made into a film.

It seems that the global literary market is a huge mechanism that thrives on mediocrity. The writers are no longer the critical arbiters of taste but are a fragile node in a vast network of literary agents, publicists, editors, talent curators, and publishers. What started as a revolutionary process of the liberation of the writer with the printing press some centuries ago is at the risk of becoming a banal activity and it is visible in the sponsored literary festival.