I don’t hold a high opinion of literature festivals. Usually hosted in Condé Nast Traveller destinations, the likes of Jaipur and Edinburgh, I find most literary fests to be self-adulating gatherings of intellectual elites, and their fawning disciples. A close-knit community of the world’s Pulitzers, critics, self-anointed connoisseurs of art congregates every year in global capitals of culture, to engage in meaningless dialogues on postcolonialism, globalism, and whatever other ‘ism dominating today’s lounge-room banter. In defiance of all things sacred, it forces upon us a public demonstration of an inherently private art.

Aren’t writers and artists to be known through their works, the characters they conjure? Do we really need to be six-feet away from Naipaul? Perhaps, when we can gain greater intimacy through reading his prolific novels?

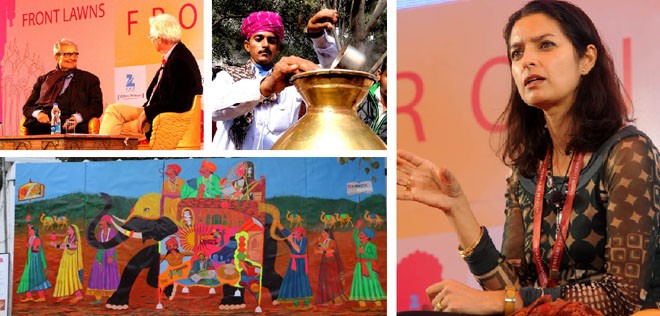

In spite of my numerous reservations, I found myself taking part in a similar gathering this year. Ironically, in Condé Nast-approved Jaipur, India. Yes, how could I betray all of you out there, who too loathe the sight of corporates shaking their hands clean with the custodians of our conscience? Jhumpa Lahiri presented to you by Dove India? Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) is frequently disregarded as a ‘glitzy mela’ of cultured Indian and non-Indian elites.

One of the many criticisms, regarding the fest, also concerns the majority of ‘white’ writers and academics in panel sessions, passing neocolonial judgments on all aspects of Indian/subcontinental culture and politics.

But one scrutinising look at the demographics of JLF this year proved to the contrary. There were senior citizens in wheelchairs, crowds of students paying pilgrimage from all corners of India to the art form, filling in the same spaces as veteran Bollywood actors, Nobel Laureates, and reputed authors of The New York Times’ bestsellers.

In its short eight-year run, JLF has and continues to offer free entry to book lovers and aspiring writers with their neatly folded manuscripts in tow. It draws crowds that are as fresh-faced as they are large. Looking to find a seat for Amartya Sen’s upcoming session? You might have to compete with a bespectacled local schoolchild, attentively taking notes for an essay on Sen’s latest foray in the limitations of global microfinance. It’s a deeply poignant sight to behold, in an underdeveloped country where the arts remain in the domain of the rich and powerful. Rickshaw drivers and chai wallas may be stopped from entering galleries and libraries in the rest of India; but at Jaipur, at least for a week in every January, they are welcome to access, share their ideas and ultimately challenge those who possess the keys to the doors of high culture in Gandhi’s India.

It may be a ‘tamasha’, but we need it. Asia’s largest free literary festival, JLF has grown to be a thought provoking, incredibly diverse forum that attempts to make sense of our changing worlds and the multiple realties we inhabit through the prism of literature, film, art and music.

This year, at the lawns of Diggi Palace, JLF’s scenic Rajasthani venue, the topics ranged from the impact of globalisation on the English novel to the themes of gender and sexuality in ancient Indian literature.

Collaboration was the keyword as American writers sat along with their Indian counterparts on panels moderated by prominent personalities, including Pakistan’s Ahmad Rafay Alam.

Spanning linguistic borders and crossing into political boundaries, it was a joy to hear South Asia’s leading cultural theorist Professor Homi Bhabha exchange notes with America’s Martin Puchner on Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. I smiled to myself as I firsthand witnessed Jaipuri locals in the audience pile into the festival book store after the session, returning with Random House India copies of the famed novel. Clearly, a literary public was being forged at Jaipur.

India may be the world’s leading subscriber to English newspapers, but English remains out of reach for most of the country’s rural population. Co-founder and director of JLF Namita Gokhale opened the first day of JLF 2014 with a firm commitment to shed light on the "endangered languages" of the Indian subcontinent.

To this end, a series of sessions were devoted to a strand of readings and dialogues on the survival of languages, nearing their extinction in an increasingly globalised world. The Bhaskar Bhasha Series, courtesy of Zee Entertainment, brought together Indian writers including the Malayali Keralan writer Benyamin Daniel, whose 2008 novel Aadujeevitham (Goat Days) is an extraordinary story of an Indian labourer’s plight in Saudi Arabia.

These underrepresented storytellers of India’s paradoxical realities sat in the company of their translators, who are invariably uninvited to global literary festivals, the likes of JLF.

Since time immemorial, translation has bridged gaps between seemingly disparate cultures. Without it, we would never have discovered the sheer ingenuity of Colombian-born Gabriel García Márquez’s magical realism, or for that matter, the melancholic beauty of Naguib Mahfouz’s Cairo.

Speaking on a panel with America’s Jonathan Franzen and the Booker shortlisted writer Jim Crace, the Indian-American writer set her eyes on the US literary scene, calling it out on the "the lack of translation, the lack of energy put into translation in the American market."

Lahiri, who now divides her time between New York and Rome, was visibly disgusted at the lack of interest shown by the US publishers in translation. "It is shameful that there is lack of translation in the American market. I know I am making a judgment, but I guess that is what it is. Living out of the US gives you a completely different perspective," remarked a pensive Lahiri.

Labelling American literature as "massively overrated", the author of The Lowland felt "there is so much literature that needs to be brought forward, and the danger now is that it’s getting even less exposure."

Besides the usual suspects, JLF 2014 featured a number of activists, working in fields as varied as sexual trafficking and natural disasters. Feminist icon and leader of the late 1960s women’s liberation movement in America; Gloria Steinem proved to be a big crowd-puller at Jaipur. If not for the generosity of a male ally, I would have had to stand along with the dozens of men and women lined outside the tent, eager to catch a glimpse of a woman who changed the course of gender history for them and others.

With a series of rapes and cases of sexual harassment rocking India, including 2012’s Nirbhaya rape in Delhi, there was a renewed interest in the Indian audience to draw on the experiences of their allies in 1960s America. The poster-girl of feminism, Steinem personally paid tribute to India’s women’s movement for its resilience in the face of rampant misogyny: "I got to see for myself, that it is work done by activists, by people on the ground that prompts real change".

Her talk was part of a new theme this year called Women Uninterrupted, a conscious effort by JLF’s Namita Gokhale to seriously engage with the unsung female voice in the arts and politics.

In a region still in its early postcolonial phase, Jaipur Literature Festival 2014 was a powerful reminder of India’s and South Asia’s strong literary roots, predating many civilisations and empires. JLF has given birth to and inspired an estimate 68 literature festivals now being celebrated across neighbouring countries. Scheduled to be held this month, the Lahore Literary Festival has revived and revamped the shrinking space for the arts in Pakistan. The Jaipur spirit is contagious and we are all impacted by this expanding community of writers and readers and booklovers in South Asia.

As the festival drew to a close on a rainy Tuesday morning and crowds thinned in Jaipur, festival founder William Dalrymple remained hopeful, tweeting "the heavens may have opened but nothing will keep the crowds away." He was right. By afternoon, familiar faces appeared in the lawns of Diggi Palace. Absolutely nothing could keep them away.