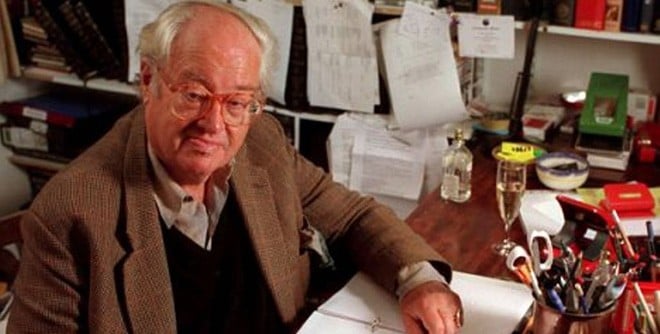

In the years between the two World Wars, Britain produced a score of distinguished novelists. On my bookshelves lie Anthony Burgess, Iris Murdoch, John Mortimer, Evelyn Waugh, Kingsley Amis etc etc., all major writers of fiction. The name I am picking up is John Mortimer, novelist, playwright, screen-writer, broadcaster, and an excellent television interviewer, who had a remarkable knack of drawing out something unexpected from the high and mighty personages of his era.

I remember watching him interview the arch Tory politician, Enoch Powell, (he, of the ‘rivers of blood’ speech). During the course of their conversation Powell said he liked playing music when he was young, but never played it now. "Why don’t you play it now Enoch Powell?" asked Mortimer in a most innocent manner. Powell pursed his lips for a moment and then said, "because it doesn’t do to waken unfulfillable desires."

It is conceivable that John Mortimer has not been rated as one of the finest writers of fiction and drama because he is reported to have said, "God is an incredible bastard". Actually, he never said that. What he said was that there was a remark in the Evelyn Waugh diaries about Randolph Churchill (Winston Churchill’s son) when he was ill and had nothing to read and so read the ‘Old Testament’. He, Randolph Churchill, looked up and said, "Incredible bastard God was."

Mortimer began his career in 1942 as a fourth assistant director in a film unit. It was an unimportant making-the-tea and helping-the-director job. He was supposed to say "Quiet please" at the beginning of every shot. He was so shy and timid, or both, that when he uttered the words "quiet please", nobody paid the slightest attention; they all went on with their loud hammering, or chattering, or playing pontoon. And then he yelled at them, "Quiet please, you bastards" and they all went on strike. He was sacked.

The people in the film unit told him that he was clearly a disaster as a fourth assistant and that he would better become a script-writer. The script-writer of the film he was working on, was the kindly Laurice Lee, who showed him how to become a script-writer. And he became a script-writer.

John Mortimer really began to write in order to have something to read to his father who had gone blind. Mortimer senior, a barrister, went blind one day when he was pruning his apple trees. He hit his head in the branch of a tree and the retina left the eye balls of his eyes. He never moaned about it and carried on with his legal career as well as he could with his wife reading out briefs to him on the commuter’s train upto London. Neither he nor his devoted wife ever referred to his blindness.

Mortimer senior was a jovial character and a committed atheist. One moment he would rage at his wife for offering him a runny egg at breakfast and the next moment he would happily sing:

She was as beautiful as a butterfly

and as proud a queen

Was pretty little Polly Perkins of

Paddington Green

Father and son spent a lot of time together. The son was greatly influenced by the father who was always laughing at jokes. Mortimer recalls that his father never offered him any advice. The only piece of advice he ever gave his son was not to smoke opium because Coldridge had smoked it and it caused him to have terrible constipation.

One of Mortimer’s novels (also a TV series) ‘Paradise Postponed’ examined the state of English rural and political life since the Second World War. When asked what was the ‘Paradise’ he wanted, he answered that he didn’t want any paradise. Paradise would be unbelievably tedious, he said, and recalled his father saying, "What a terrible idea it would be, like living in a huge transcendental hotel with nothing to do in the evening", He would like to live in England as it is with a little bit more social justice, equality and a reasonable treatment of everybody. It wouldn’t be paradise, it would be better.

Mortimer had been a practising barrister for many years before giving up his profession and taking to full-time writing. Judges, it seemed were not his ideal companions in eternity. An interviewer once wondered whether he ever longed for the idea of God as judge, as the ‘celestial Lord High Justice’, togged up in wig and robes? "I couldn’t bear human judges," he replied, "I certainly could not stand a celestial one. I think judgement is one of the worst weaknesses of human nature. If we could get away from judging people, we would be infinitely better off." He went on to say that there was a terrible disease called ‘Judgitis’ which the judges got very rapidly and, as a result, became ill-tempered, impatient, intolerant and sounded off with ludicrous sorts of generalisations about human behaviour.

Like his father, John Mortimer, too, was a practising barrister for nearly sixteen years before he gave it up to be a full-time writer. His practise at the Bar was not entirely fruitless (he was forever defending petty criminal murders, debauched bookies and other down and outs), it led him to create the character of Rumpole. His ‘Rumpole of the Bailey’ novels are dramas of good and evil, of judgement and mercy. They were later turned into an immensely successful television series.

Horace Rumople, who calls himself ‘an old Bailey hack’, is a delightful character: crusty, unmalleable, jovial and unambitious. He has no desire to move to a higher position. He refuses to take silk, he spurns the offer of being a county judge. All he wants is to have the simple pleasure of defending his clients. He loves the verbal tussle of cross-examination and pricking the pomposity of judges.

Like his father, Rumpole is full of loveable eccentricities?: His attire is not in keeping with what is considered to be suitable for a barrister. His waist-coat is smeared with cigar ash, he wears on old hat and he eats greasy, fried foods. He drinks wines of a questionable quality and he calls his wife "She who must be obeyed," (a reference to the fearsome queen in Rider Haggard’s famous novel ‘She’). The novels were turned first into a Radio play and then into a television play. Later, it was developed into a highly watchable and vastly amusing television series, which began in the late seventies and ran for fourteen years. I saw a few episodes recently and found it as funny and fresh as it was in 1978.

I admire John Mortimer for his humour, his humanity and his trenchant spoofery of the kind of conservatism known as Thatcherism.