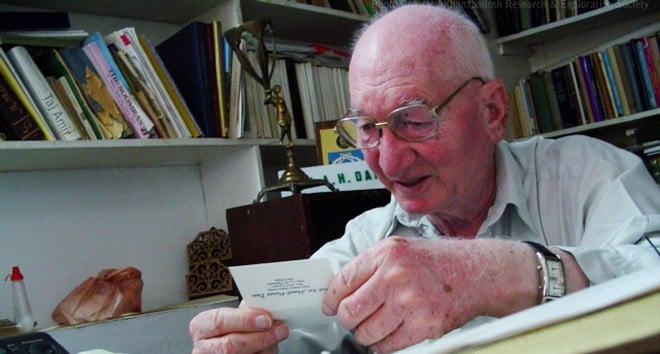

January 26, 2009 marked the end of an age in the realm of Pakistani social sciences with the demise of Professor Ahmad Hasan Dani. Popularly known as a legend archaeologist, Dani has to his credit singular contributions in the disciplines of history and anthropology.

Professor Dani turned out to be a prolific writer. He generously wrote on various aspects of archaeology of the region such as epigraphy, art and architecture, pre and protohistoric and historic period archaeology. He was trained under the last Director General of Archaeological Survey of India, Sir Mortimer Wheeler (1944-48), at his Taxila Training School.

The establishment of the school shortly before Independence left behind personnel in the field to inherit British archaeological legacy. Among other things, he also knew Sanskrit language. In the first decade after Independence, he worked in collaboration with scholars from abroad.

His inquisitive spirit, which I would like to term as the greatest determinant of his scholarship, was a unique aspect of Dani’s historical reconstructions. It made him a modern social scientist in the real sense of the word. He synthesised scientific methodology with an intuitive element and cognitive understanding. And it was this inquisitive mind which always kept him abreast of the ever-new theoretical and methodological developments in the field of archaeology.

Theories in any academic discipline wax and wane and the process, no doubt, is dictated by socio-cultural and political contexts. Under new external developments, an existing theory often fails to fulfill the needs of academics and researchers. This theoretical crisis results in the emergence of still another theory which, in turn, holds good for another while. This process is termed by Thomas Kuhn as ‘paradigm shift’.

Archaeology is not an exception to this rule. It has different paradigms and paradigm shifts in its history of about two centuries. And Professor Dani’s familiarity with all this assigns him a respectable place in Pakistani, even South Asian archaeology.

Dani was primarily trained as a culture-historical archaeologist. Culture-historical archaeology is basically the study of past cultures and, hence, is concerned completely with historical reconstructions. It establishes chronology with the help of systematic study of material remains. Change in archaeological culture is always assigned to either migration or diffusion (in other words ‘movements of peoples’).

Indo-Pakistani archaeology in the British period was dominated by this culture-historical approach; a legacy still preferred and widely used in this region. Dr Dani adopted this approach in all his archaeological researches of great importance. And all this took place during the first and active period of his career till 1980. His study of the Gandhara Grave Culture, Gumla site (D.I. Khan) and some others are characterised by this theoretical understanding and related methodology. He established chronologies and reconstructed cultural histories.

Notwithstanding the fact that Dani was a culture-historical archaeologist, he remained receptive to new methods and theories. This thesis is substantiated by Dani’s embracing of the call of New Archaeology aka processual archaeology. The new movement revolutionised archaeological activity in the 1960s and reigned supreme in the 1970s. It dismissed culture-historical archaeology as futile and trivial pursuit. Now the prime aim of archaeology was declared to be the study of cultural process. It means that human culture is part of a larger ecosystem and it is shaped by its environmental setting. Thus, archaeologists should study the relationship between the subsystems of this greater system.

It seems that Dani became familiar with New Archaeology in the latter part of his professional life, most probably in late 1970s. Indus Civilization: New Perspectives (edited by Dani, 1981) substantiates his attraction to new developments in theory and methods. But a more suitable example is a later book, Perspectives of Pakistan, published in 1989 (which aims at popularising history rather than being a so-called serious scientific work), in which Dani elaborates the importance of environment on built culture. He calls upon his South Asian colleagues to take account of these trends in their studies and researches.

This is a significant development in relation to Dr Dani’s scholarship. He entered the arena of New Archaeology with a special focus on studying cultural systems and human behaviour within an ecological perspective. Unfortunately, all this happened at a time when he had already spent the most active part of his professional career. Resultantly, he failed to introduce new or updated trends in the field of archaeology in Pakistan.

It is too early to determine whether Dani left a legacy or not or whether he left a school of thought or not. It is for the new generation of archaeologists to determine that.