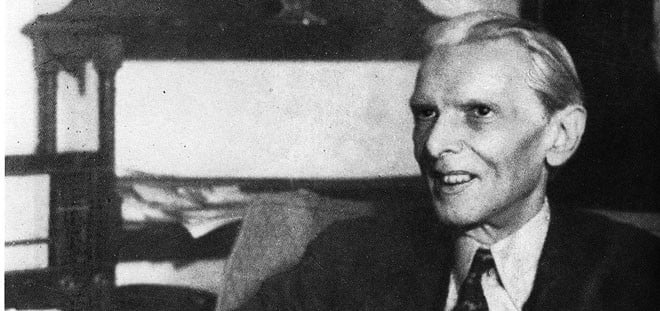

It is that time of the year again when many of us celebrate Christmas -- and an even greater number start apologising to Mr. Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

There have been multiple articles in recent weeks as well as ‘trending’ activity on social media that bemoans how we have betrayed Mr. Jinnah’s vision. The appeal of this, largely self-constructed, ‘vision’ is that it allows us to accommodate most things we deem desirable within it. There is an irony in this too. It has huge emotional appeal and it is partly manifested when people, old and young, exhort and extoll ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’. However, in theoretical and practical terms this is deeply problematic -- at least for me.

To criticise the present by pointing to ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’ or his ‘vision’ assumes that there was a somewhat clear, singular or even united vision. Since Mr. Jinnah is not around to explain it himself, this means debate and argument over the founders’ intentions. This, of course, is not unheard of in other countries -- say the United States -- and people try to arrogate to themselves the power to identify parts of this vision. But we cannot ignore the fact that a lot of this is historical guesswork -- particularly in the case of Mr. Jinnah who did not write or endorse anything such as the Federalist Papers and did not preside over anything similar to a convention in Philadelphia where certain principles were agreed upon. Nor did he have time to set his vision down on paper. And how could he? Time was limited but the problems were overwhelming and he was doing what he did so admirably well -- being a master tactician.

Like any good lawyer, Mr. Jinnah knew his audience and was brilliant at deciphering what would appeal to each respective group. But while this may work as a candidate running for election or a lawyer arguing two different (even conflicting) cases before the same judge on the same day, this is not always the best strategy for the long-term when a country is born.

So what was his vision? The speech on 11th August, 1947 (championed by secular liberals) or the one he made to the Bar Association in Karachi in March, 1948 saying that Pakistan will be an Islamic state following principles of Sharia? Of course you could argue that there is not necessarily a conflict as a welfare Islamic state would safeguard the rights of religious minorities -- but that is theory, not a vision based on political realities. And even if you concede the welfare Islamic state, what happens to those championing a secular Pakistan? You see, with interpretations, one side usually loses. And this gives power.

Let us also not forget the fact that ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’ was no bastion of federalist principles or respect for provincial autonomy. Ethnic nationalism, a legitimate force in any federal structure, was dubbed ‘parochialism’. Assemblies were dissolved in the then NWFP when that unit of the federation did not follow the path the centre wanted it to. Urdu was celebrated over Bengali. Fears of discrimination on the basis of ethnicity were sidelined instead of being engaged with and accommodated. All of a sudden, the rhetoric of nationalism took over. That you had been a Pathan or a Bengali was supposed to be put on the back-burner since after a ticking over of the clock on 14th August, 1947 you became a Pakistani. And somehow that was supposed to take care of everything. You were supposed to be united and just forget the actual human experience of an identity that mattered to you.

This was partly ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’. It was not of his making entirely and he did not create all the problems but he did not have and could not have had a ‘vision’ for such a new country -- grappling with a multitude of issues.

Convenient arrangements were reached with local land-lords to compensate for the lack of Muslim League’s political base in the newly created Pakistan. Islam was the slogan and Pakistan was your blanket -- except that it could not be that way.

Was there great provincial autonomy in ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’, was there great religious freedom? He did not have time, you say? Well then that is precisely the point. Why is ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’ the benchmark then? What was his Pakistan? His statements depended on the audience and that is perfectly understandable. He was speaking to the world community, to the religious zealots, to the millions with hope in their hearts -- all at once.

There is no doubt that Mr. Jinnah was a brilliant lawyer and an immensely skilled politician. But was he a long-term visionary? We should be able to question that because if the basis of Pakistan was an argument then this land must celebrate all arguments -- no matter how outlandish.

Whether he wanted a secular state or one following Sharia should be irrelevant today. He cannot come back and create one for us. And whatever he wanted he probably would have had a really tough time creating either one -- because in a democracy it is not just vision that matters but populism. And an Islamic state might well have been what most voted for in a populist election. But that means we keep going around in circles. And the only clear thing in this whole debate is this: what the people of Pakistan want is precious and should be followed.

Suppose a succeeding generation fundamentally disagreed with the founders’ vision and wanted to re-invent a state’s ideological moorings. Would it be fair to say that all succeeding generations are bound by the vision of the founders? How is that respectful of democracy? How is that even practical at figuring out what people wanted decades ago?

And if you just go by the rhetoric of the time and ignore the policies, then you really are not being a ‘visionary’ yourself.

Of course religious minorities should be respected and of course the state should not interfere in matters of personal faith. Agreed -- all of it. But is that the ‘vision’ people champion? The rhetoric is the same today and yet the boundaries keep shifting. What policies existed back then that we cannot think of or implement today? And it is not as if we in 1947 had implemented much of the liberal rhetoric.

It is not worth fighting over Mr. Jinnah’s ‘vision’ since the Pakistan of today demands that we listen to the present and not the voices that we have historically ignored.

For my part, I find it quite baffling that people each year write the "I am sorry, Mr. Jinnah" articles or claim that we failed our forefathers. The things that we attribute to our forefathers say more about our own aspirations than theirs. And that is what we should remember.

Our lives should not be dictated or be torn apart by debating over what the founders wanted. It is about what we and our children want.

The only people we should apologise to are ourselves. And we must also not forget that we have made significant strides in the past few years -- particularly towards provincial autonomy. We did that because we wanted it -- not because we are anchored to a vision.

Our dreams and aspirations today are what matter. And these should prevail over all apologies to a romanticised past with no clear meaning.