To me, Sajid Qureshi always seemed to cut a distant, romantic figure of an artist. When I was a young boy in class eight, he was the icon of a modern, metropolitan, bohemian who moved to Lahore and worked among a group of artists at the premier art institution of the country. In Hyderabad in the 80s, our art teacher, Sain Fateh Halepoto, would show us his sketches and book titles with great pride -- his prize pupil -- and tell us that illustration was a powerful medium of the region. He would share the art books Sajid sent him as reference.

Sajid’s paintings of Lahore were sober, impressionist and as bold as any European artist, so many of us in Hyderabad aspired to be like him. Even at a distance from us, he broke the cultural monotony of the place, we felt changed, rejuvenated, wrote him letters and tried to pick up his swagger -- his Sindhi slang, his style of being and of making art. We saw his thesis show as a video recording in Sindh.

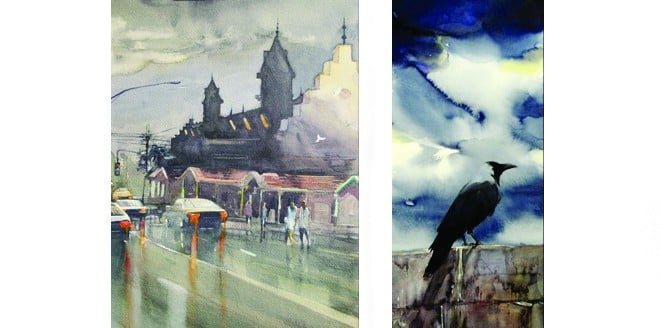

When I visited him, his life seemed so glamorous to me: days of hard work at the studio and open conversations with teachers and senior artist like Colin David, Khalid Iqbal, Lala Rukh and Iqbal Hussain. Sajid was confident always, drawing with much ease and facility, refusing to use black or white in his paintings to make the work easier but deepening the tonal quality. His paintings meant nothing more, nor less, than studies in colour, beauty, space and light.

I moved away from illustration after observing the tonal power of his work. We would discuss his work with him -- formal, intellectual concerns and he always passed on books, ideas, emphasising the practice and understanding of anatomical drawing.

I would walk along with him in the streets of Anarkali and ask him when he got the time to paint since he was so popular among people, especially women. He told me he was left handed and could draw while people spoke to him. He told me he worked every day or at night. Later, I would ask him why he didn’t show his work in galleries and he replied he drew in water colours, making book illustrations for publishers.

I had known his illustrations of Sindhi books that always stood out from among other, more forced and deadened images on titles. I often wondered: how long it would take to become an artist like him?

As a student I came to learn how long it took when I learnt about the many masters of Sajid: Degas, Rembrandt, Lucien Freud, Winslow Homer. His language came from many places but he spoke about the streets of Lahore and Hyderabad. After the success of his thesis show, we expected he would launch his career as an artist.

He joined the Urdu Science Board where I saw many of his book titles. He had a show around this time but it was not very powerful and his ease with the medium seemed to have wavered. In Lahore, he did some commissioned portraits, fresh and pleasing. In Sindh, he did many portraits and brightly hued drawings for himself.

He used to say, this is not the right time for art. Now mediocrity will rise as the art administration changed completely, particularly when the age bar came into effect. The institution was no longer about serious debate among mature people. He used to say, even a long time ago, that we have to wait for the right time and then he would give up his job and paint full time.

I remember one of his earliest drawings in a sketch book of labouring men going up and down bearing heavy loads, their anatomy so perfect they looked like Greek warriors who had been taken captive and forced to build a mountain fortress. The stress in their bodies, the weight on their shoulders and how it bent them were well studied figures.

Another drawing was of many hands -- clenched, unclenched -- like Degas’ ballerinas at rehearsal with the arched bodies of a skilled performer. Sajid used to recount the story of Degas who visited Ingres and asked him how he could go about learning the master’s craft. He was told, "Young man, draw, draw, and draw." Looking at Sajid’s work inspired me to work harder.

Sajid had the ability to change time with colour -- change form and space with imagination. Often I found him engrossed in books, at other times in paintings. I never saw his work in galleries. Never saw him at art workshops or at lectures. He was always the same, always working, but he was not considered an artist by the academy that bred him. They called it skill, his concern with drawing and painting, called him an illustrator without concepts. I always wondered about that.