Twentieth century produced three towering figures of known for their fight for racial justice and freedom from white oppression. Nelson Mandela was the most recent in that distinguished pedigree.

The earlier ones included Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Each one was nurtured by the example of his predecessor. Gandhi laid the template for both King and Mandela. Mandela’s example nurtured Barack Obama in turn. Yet there was a fundamental difference too. Whereas Ghandi and Luther King largely drew upon religion, Nelson Mandela, in contrast, rose above religion and based his fight for equality and justice on non-religious morality. This explains, partly, his enduring appeal for the whole of humanity.

He was a great moral force in politics. His passing away, or rather slow fading away under relentless media blitz, has robbed us of a permanent reference point in reconciliation, ethics and morality in politics. Even in 1964, at the Rivonia trial, he was clear-eyed about the moral vision that drove his politics when he said:" I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I’ve cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities."

He adhered to this ideal throughout his life. And this ideal kept his political vision unclouded even after long years of incarceration under the apartheid regime of South Africa.

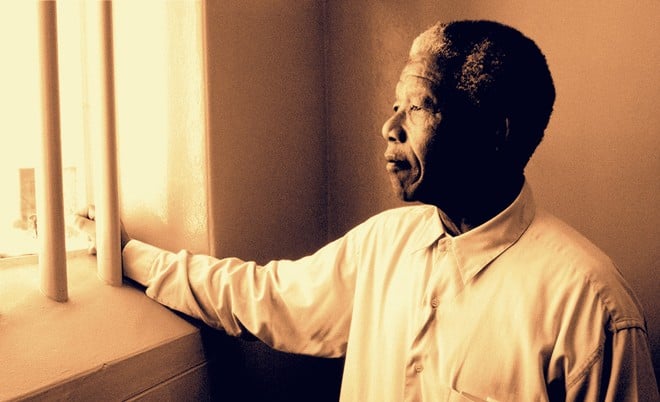

And to this ideal he stayed true throughout his life even after his release from the prison. Two enduring images that flashed across the TV screens in the aftermath of his demise are eternally etched in our memory. The first image is that of a proud crusader for justice, draped in the robes of a Xhosa chief, ramrod in built and convictions being led to the court in 1963.

The second image is that of his release from the prison in 1990. Nothing in the second picture has essentially changed: he still looks exalted and tall, full of moral conviction, except that the years of incarceration seemed to have aged him. Yet he put his bitter past behind and constantly beamed a sunny smile after his release showing his magnanimity of spirit. In a true spirit of accommodation, he reached out to all South Africans without any heed to the colour or faith they professed.

This reconciliatory outlook led to the non-violent transition to democratic South Africa. While in and out of the office, he steadied the wobbly nation with his reassuring and saintly presence. The old wounds of bitterness and racial divides he healed through the truth and reconciliation commission which has become a template for a peaceful resolution of long-entrenched conflicts the world over.

Yet, this remarkable man did not begin his journey in the politics of reconciliation. As a pragmatic crusader for justice, he did espouse the use of bullet and bombs to fight the brutally repressive regime. However, as politics followed the moral force of his struggle, he adopted reconciliation and forgiveness as his guiding principles. When time required, he did not hesitate donning the cap of the Springbok rugby club -- a symbol of white supremacy and exclusivity -- in an effort to unite the whole nation.

Acts like these showed his visionary sweep and superhuman magnanimity which characterised his remarkable life.

His other contribution is the elevation of the grubby business of politics into a force for good. Mandela showed by his example that things can be turned around through politics, leadership and the vehicle of a political party. A firm and unflagging believer in political organisation, his commitment to the African National Conference (ANC) was total. So much so that he endorsed the controversial majority decision to appoint Thabo Mbeki as his successor.

In a further demonstration of his devotion to the ANC, he allowed himself to be wheeled to the current president Jacob Zuma’s election campaign in the most recent elections. Similarly, despite criticism from right wing and the West, he kept the African Communist anchored within the ANC tent. In fact, Christ Hani, the leader of the communist party, was considered his heir before his tragic assassination.

It is now up to the new leadership to carry on Mandela’s legacy of reconciliation and social justice which were the central features of his political vision. However, there are growing fears that with Mandela’s unifying glue gone, the party may splinter into factions or breakaway parties.

Mandela also never hesitated in acknowledging, praising and paying court to leaders such as Castro and Qaddafi -- pariahs in the West -- for their consistent support to the ANC over the previous decades. In a similar spirit, he made two visits to Pakistan as a token of his appreciation for Pakistan’s long-standing support for the ANC. Mandela was a vocal critic of Western intervention in Iraq, too.

Unique among the world historical figures, Mandela spawned movements that politicised a huge number of young people in the West. Anti-apartheid movement in the UK was one such outfit which played a hugely influential role in catalysing the sporting and trade boycott of South African racist regime. Such copy cat movements all over the world were instrumental in solidifying his image as a global icon.

Since the 1990s, the expansion of global and social media has also contributed to a process of his beatification. Yet Nelson claimed no sainthood status for himself or those around him. He did not let the hagiographical shroud draped over him to muffle his innate goodness, kindness and the ability to empathise with the down-trodden or those hard done by unjust systems.

Mandela was a truly transformative figure. He was not a revolutionary but consistently radical in politics. He will be missed at a time politics has become banal and devoid of big ideas. It could be decades before we see the like of him.

With his passing, we have lost a moral compass guiding our actions towards what is noble and moral about politics and its potential to turn things around in non-violent and gradual ways.