Southeast of the city of Lahore, off Bedian Road, there is a house. It stays relatively cool in the summer (below thirty degrees) but it has no fans or air conditioning. It stays warm in the winter, but there are no gas heaters either. It uses no imported materials, and in fact, most of the material used for its construction was non-synthetic and produced on-site. What is the secret of this house? Well, it’s made of mud.

Mud is one of the world’s most ancient building materials, and is often seen as be primitive, backwards and good only for temporary constructions. Yet it accounts for some of the world’s longest-lasting (and most famous) structures. Examples include the Alhambra in Spain, parts of the Great Wall of China, and the giant Bam Citadel in southeastern Iran. Around 30 percent of UNESCO’s world heritage sites are made of earth-based materials. Mud structures are not necessarily temporary -- they can last.

The primary concern when building with earth is to save it from getting wet. When dry earth gets wet, it loses its form, which is a problem if it is being used to support a building. But if the material can be protected from direct contact with water, there are significant payoffs. Not only does mud help effectively regulate internal temperature, it also helps regulate humidity due to its ability to absorb and desorb moisture.

There are also big benefits for the environment. The energy savings are remarkable: the preparation, transport and handling of mud bricks require only about one percent of the energy expended in the use of baked bricks or concrete. These savings result from the fact that mud bricks are not baked in furnaces (which primarily use coal as fuel) and the raw material used to make them is freely available, reducing or eliminating the need for transport. Since the material is reusable, there are no real waste products either.

These are some of the reasons that motivated Bilal Soleri, the man who decided to make the mud house off Bedian Road. He has lived for years in the US state of New Mexico where there is a very long tradition of building with mud bricks (known as adobes), and where a modern interest in this type of building has rekindled.

"I wanted to build a house that would need minimal heating and cooling, and would also be good for the environment. So I thought of using adobe," Bilal tells TNS.

He decided to talk to a famous architect who specialised in traditional building techniques and the use of local materials. Unfortunately, the architect had his own ideas and ended up trying to convince Bilal not to use mud as a building material.

"I realised that I was doing this for my own pleasure and satisfaction, and if I ended up giving in to someone else’s ideas it would defeat the purpose of the whole thing."

So, Bilal decided to try doing it himself. He did a lot of research on the subject, reading as many books as he could to help him plan everything.

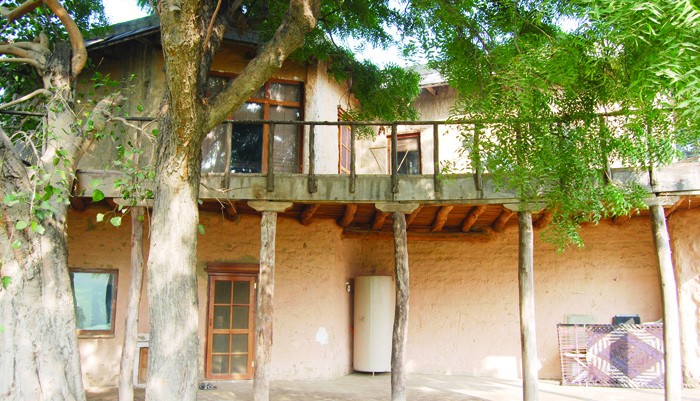

Since excessive heat is a bigger problem in Lahore than excessive cold, the house was laid out in a fashion designed to minimise exposure to the sun, with smaller faces of the house facing east and west. The foundation was made of regular brick and mortar, to prevent water from the ground from seeping into the walls. The main building material (mud) was made from the local soil mixed with water and 5% lime. The mixture was then put into wooden frames used to make large bricks that were then dried in the sun. Different frames were used to make different bricks; some with rounded edges for corners and others shaped to allow space for water and electricity pipes. These were then used to make the walls.

The roof was constructed on top with planks of local wood, extending past the edge of the house to form a veranda that would protect the walls from getting wet on the sides. On top of the wood was placed a plastic cover that would prevent leaks, and inverted earthen pots (‘koondis’) that would provide good insulation because of the air trapped underneath them. Lastly, a layer of tile was grouted in place on top of everything.

Lime (‘chuna’) was used to cover the walls, providing both colour and water protection. The circular, double-glazed windows were used for insulation, and turned out to have the added benefit of greatly reducing the amount of dust entering. For air circulation, there are two vents to which evaporative coolers can be attached if cooling and air filtration are desired. A specially designed woodstove with outside air intake and exhaust can be used for heating.

The house has been standing for over eight years now, and yet there have been no major issues. There are myriad refinements that could be made in its design and construction, but the house is still both functional and comfortable to live in. It was built without the benefit of prior building experience or formal training, and yet it has worked. If more knowledge and expertise are used, the results for mud construction should be even better.

Anywhere from about one-third to one-half of the world population already live or work in buildings made of earth, but most of those buildings are not like the one built by Bilal Soleri. In rural Pakistan, almost 50 percent of people live in mud houses, but those houses are built ad-hoc without much thought to design and are vulnerable to corrosion due to rain. Giving the people who build them a bit more awareness and understanding about how to build could help improve building standards without having to use significantly more material resources.

Karavan Ghar is an example of what this could look like. It is a project started by the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, intended to provide housing to people in disaster-stricken areas such as Kashmir and lower Sindh. Instead of building houses, their strategy is to give people the skills to build decent houses for themselves. Teams are deployed to educate villagers about how to build strong, sustainable structures using mud, and the results have been promising.

Perhaps the next steps in building materials are leading us back to where we came from: mud.