"Autobiography is the strangest of genres…" says famous Urdu writer and critic Mushfiq Khwaja, "it is supposed to tell you something about the author, but it picks on other people more than it talks about the author…it should, by definition, be a collection of true memories, but they are in fact selective memories, chosen carefully by the autobiographer, to keep his image neat and clean."

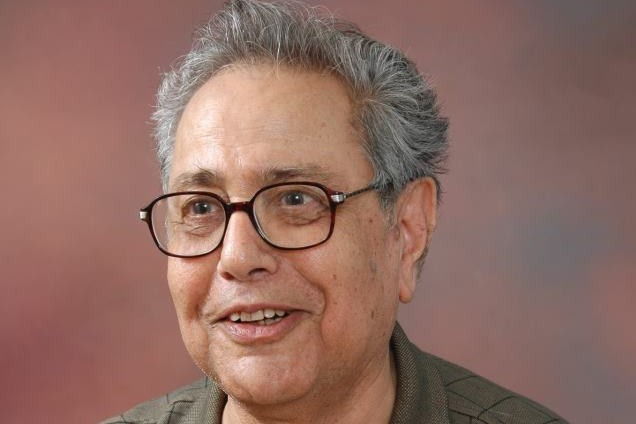

This pleasantly sarcastic remark is true for most Urdu autobiographies but let’s see if it fits the recently published memoirs of Satyapal Anand. A prolific writer as he is -- 43 books of fiction and poetry to his credit and still going strong at the age of 82 -- he considers himself a literary nomad, wandering from country to country, culture to culture and language to language. Anand writes in four languages: Urdu, English, Hindi and Punjabi. He has published five collections of Urdu short stories, eleven collections of Urdu poems, nine collections of English poems, five Urdu novels, seven books in Hindi and six books in Punjabi.

His latest work is the 552-page autobiography, which he prefers to call his literary memoirs. As the title suggests, he has divided his life story into four parts: from his birth in ‘Pakistan’ to the partition of 1947, his struggle to survive as a refugee in the Indian Punjab, his higher education and the beginning of his literary career, and finally, his migration to the West.

Anand, unfortunately, had to witness all the cruelties and atrocities of 1947 at the age of 16, when he was only a high school student. But even at that young age he had the mind of a mature humanist, and could not be provoked against any community. We can guess by the circumstantial details that his father, the only bread winner of the family, was brutally killed probably by the Muslim attackers, while the family was migrating to India, but Anand himself doesn’t say a word in this regard. Not because the incident was too brutal to be described, but because the author does not want to blame one particular community for the mass hysteria prevalent all over the country at the time.

The second part of his life story starts in East Punjab. Since he was the eldest child and the sole provider of a family of five, he had to do several jobs simultaneously to make ends meet. In this period of 13 years, from 1947 to 1960, he worked at a bookshop and a printing press, translated children’s stories from Urdu to Hindi and vice versa, wrote short stories in popular magazines like ‘Shama’ and ‘Beesvin Sadi’, and even wrote pulp fiction using various pseudonyms.

Along with all these activities, he continued his academic studies, and after earning a diploma in Adib-Fazil, doing his Intermediate and Bachelors, he finally got his Master’s degree in English Literature. During the same period he became friends with the new writers like Krishan Adeeb, Heera Nand Soz, Ram Lal, Harcharan Chawla, Surinder Parkash, Kumar Vikal and Prem Warburtoni.

Later on, when he was able to travel to Delhi and Bombay, he also developed close relationship with literary stalwarts like Sahir Ludhianvi, Krishan Chander, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Davinder Satyarthi, Balwant Gargi, and Kunwar Mohinder Singh. Moreover, he had pen-friendship with Shaukat Siddiqui, who was in India till 1950.

The second phase of his struggle was perhaps the most difficult one, but his efforts bore fruit: his siblings completed their education, his humble abode changed into a grand mansion, and his First Class First in MA English earned him a lectureship at the main University campus in Chandigarh.

In the four-act play of his life, here begins the all-important third act.

Now that he was freed from his domestic responsibilities and other immediate obligations, he pursued his professional career with earnest zeal. His PhD dissertation was on British fiction with particular reference to James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. He soon got an invitation from the British Open University to work as a research scholar, and that was a gateway to the world he always wanted to explore.

This international exposure enabled him to meet with the heavyweights of literature and arts in Europe and, for the first time in his creative life, he discovered a mysterious unity and an underlying link in human creative effort all over the globe, in all forms of art and literature. This led to his keen interest in comparative literature as a discipline, which finally became his academic specialisation. For the next 17 years he was the busiest Indian academic, travelling as a visiting professor of comparative literature, to the US, Canada and Europe. So much so that he was nicknamed "Airport Professor" by his Indian colleagues and students.

In the fourth and final phase of his fertile and productive life, he is enjoying his retirement in Virginia, US, but he is even more active, mentally and physically, than he was in his working life. He goes to Europe almost every year: during 2012-13 he has been to UK, Germany, Turkey, Denmark and Norway. He also visits Canada at least once a year.

As a poet and a poetry-critic, he has been fighting against the genre of ghazal all his life, and after his retirement this crusade has become more vigorous and intense. His heroes are Hali, Azad, Noon Meem Rashed, and Meeraji, rather than Faiz, Firaq, or Nasir Kazmi.

Satyapal Anand puts the genre of ghazal under the title ‘Orature’ (oral literature) rather than proper literature. He is of the opinion that ghazal cannot be enjoyed through silent reading; it has got to be read aloud because it has developed and nourished in the mushaera culture, where a huge audience is sitting, fully charged with the expectation of a rhyming phrase coming up…and as soon as the poet utters that phrase, the audiences release their energy in the form of loud praise (daad). This circle repeats itself after every couplet, and thus the genre of ghazal belongs more to the performing arts than literature proper.

Due to this aversion to ghazal, Anand never took it seriously. He proudly mentions incidents when an audience demanded a ghazal from him, and he composed several couplets off hand, on the stage (which were, ironically enough, praised a lot by the crowd).

An interesting attribute of this memoir is that each of the four parts begins with a relevant extract from Buddha’s life story. Another feature that grabs our attention is a complete index (30 pages) of personal names at the end of the book.

What this book lacks -- and very badly so -- is proof reading. There are printing and spelling errors almost on every page, and one wonders if the author ever saw the draft before it went to the press.

Katha Char Janmo Ki (Memoirs)

Author: Satyapal Anand

Publisher: Bazm-e-Takhleek-e-Adab, Karachi

Pages: 552

Price: PKR500